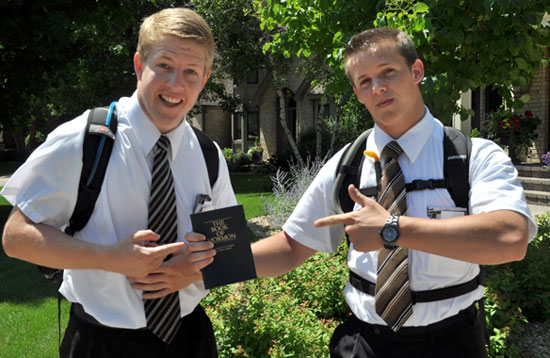

(Leif Hagen)

Unless you have been living in a cave or asleep for the last half year, you know that we are living in an era that the media has dubbed the “Mormon moment.” Aided by the religious affiliation of not one but two Mormons, Mitt Romney and Jon Huntsman, in the latest presidential election cycle, this moment has led to a flurry of media interest in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. It also hasn’t hurt that at about the same time the creators of South Park, Trey Parker and Matt Stone, produced The Book of Mormon, a smash Broadway musical that placed the Latter-day Saints squarely in the public eye. In other words, we’ve seen a “perfect storm” of interest in all things Mormon in the past year.

I must admit to feeling some dismay about this course of events. I have been teaching a class on Mormonism at the University of North Carolina since 1999, and several years back I realized that there was a tremendous need for greater knowledge of this religious tradition. So, I am in the midst of researching and writing a book about the history and current status of Mormonism. And the more that happens in the news, of course, the more there is to write about—so, as a historian I just want to stop the deluge of news for a few days. In my larger project I seek to explain the history and current configuration of Mormonism to outsiders. But I also hope to cast light on what the Mormon experience in the United States tells us about the rest of us, about our notions of which differences are valuable and which are threatening, and about our tolerance of religious variety and the limits of that tolerance.

My task is to bring some needed historical perspective to current collective conversations about Mormonism in public life. Because I believe that this moment, like many such events that seem to come out of the blue, actually has been about 100 years in the making. In short, my argument is this: since the beginning of the 20th century Mormons in the U.S. and other Americans have struggled with a particular but pervasive problem: how to recognize Mormons as U.S. citizens, with all the obligations and privileges that attend that designation. The last few years marks only the latest round in a series of events that have shaped, but never completely resolved, this question.

Citizenship may seem like a simple and obvious idea to us today, and its relationship to religious belief and practice has been sorted out in the courts for decades. In the narrow sense, citizenship denotes a particular form of political representation, as well as the potential for participation, in the federal government. So it is worth bearing in mind that throughout the nineteenth century, the Mormon movement was effectively barred from making any substantive claims on U.S. citizenship. Joseph Smith, Jr., a young farmhand from upstate New York, founded the church in 1830. Very soon, however, Mormons were forced to flee the East and regroup in the Midwest—first in Missouri, where in the mid-1830s Mormons began to gather in Jackson and then Clay counties, and later in the newer settlements of Caldwell and Daviess counties. From the start their arrival, coming as it did in large numbers (in the thousands) and through continuing streams of immigrants from both the eastern states and Europe, caused political and economic tensions with older settlers. Following years of sporadic violence and threats on both sides, the Mormons were forced to flee Missouri after Governor Lilburn Boggs issued an order in 1838 declaring that church members should leave the state or be exterminated. A worse fate met them in Nauvoo, Illinois, where after a few years of relative calm Smith was killed by a mob and the community once again forced out. My point in recalling this early history is simply to underscore that, as much as the Mormons appeared to threaten the political stability of older settlements in Missouri and Illinois, their tenure in these states was never long enough or peaceful enough that the issue of Mormons as political actors came to the fore.

The scattering of Mormons after 1844 brought a new chapter to this saga. The religious movement split into a variety of factions, most of which were relatively small and fairly quickly assimilated into American society. The largest group of exiles, perhaps 5,000 or so, moved further west to Utah, where over the next half century they built a self-sufficient society in the Salt Lake Basin. This group, by now known as the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, represented the germ of a community that would grow to over 200,000 people, the majority of them Mormon, by 1890. The U.S. government was not far behind; Mormon settlement in Salt Lake began before the Mexican War, before Utah had any status in American political life and was still a gleam in the eyes of those believers in Manifest Destiny. Once annexation occurred, however, the Mormons found themselves again tangling with the federal government over their practice of polygamy; but this time they were blocked from full participation in the nation because they lived in a territory instead of a state, a district without representation in Washington or the ability to elect its own leadership. Over the next half century the U.S. government and church leaders conducted an elaborate cat and mouse game: the U.S. held out the carrot of Mormon citizenship in exchange for the Mormon promise to obey the laws of the land and discontinue the practice of polygamy. Failing to convince the Church to capitulate, the federal courts turned the screws and made life increasingly difficult for Mormons; by 1890, all church properties, including the LDS sacred temples, were in imminent danger of federal confiscation, and as a result the religious community teetered on the precipice of economic collapse. Finally, in a dramatic meeting of the minds, the Church ended its practice of plural marriage and the U.S. government conferred statehood in 1896.

This, then, is where our story really begins: With statehood came the new problem of the Mormon citizen. Although many Americans had harbored suspicion toward the church for years, the threat that it posed had been contained in the far West and limited in its ability to affect the fortunes of the nation. The nineteenth-century Mormon threat was a moral and symbolic threat, but never seriously a political one. Now, Mormons would be participating in the daily practices of public life. Once statehood was conferred, their “threat” would be unleashed in the halls of Congress and eventually, as we know, would lurk in waiting outside the West Wing itself. The “western” problem of Mormonism now became the internal challenge of the Mormon within the body politic.

If this is how Mormonism looked from the outside, let’s now turn our attention within the religious community. How did the Saints set out to embrace this new political identity? How did individual church members, previously cushioned from the need to become political actors by the disempowering embrace of territorial status, step into this brave new world of citizenship?

THE FIRST THING TO BE said is that the Mormon Church had been honing its public relations skills from its earliest years. There were two simple reasons for this: first, Mormons faced immediate criticism and public defamation from detractors. In 1834, a scant four years after the founding of the new movement, the newspaper editor Eber D. Howe published the scathing Mormonism Unvailed [sic], a compilation of accusations, affidavits, and other evidence of what Howe took to be the frauds perpetrated by Joseph Smith. More criticisms followed, and Mormon apologists early on fell into the pattern of spreading the word through debate and polemic, arts that required superior communication skills. Having been born in the early years of publishing, the Mormon movement availed itself of the latest technology—the printing press—that could help to plead its case to the public. The second reason for their P.R. savvy, connected to the first, was the deeply ingrained Mormon missionary impulse. Smith counseled his followers that their primary task was to spread word of the restoration of the gospel to all peoples; within months of establishing a church, the new prophet sent followers to preach to American Indian populations to the West, and shortly thereafter sent another small band to England to begin a mission to Europeans. Missions required robust marketing skills, and Mormons knew that theirs had to be especially good in places where other Christian groups not only had already landed, but had also spread word about Mormon heresies. Pragmatic in their approach, Mormons sharpened their tools in situations of intense competition for followers and a desire to level the playing field with other Christian groups.

In their years of isolation in Utah, moreover, the Saints also practiced public relations by appealing to the small bands of cross-continental travelers who stopped for a visit among the odd but generous Mormons. Tourism increased dramatically in the 1870s and 1880s with the completion of the railroad, and Mormons used their notoriety as the ideal opportunity to charm guests with their well-appointed hotels, clean city paths, and ingenious agricultural techniques. Dozens of books and memoirs remain as a testimony to this period when “visiting the Mormons” represented the height of adventure travel for many well-heeled Americans—some of whom then became outsider advocates who could testify to Mormon virtues. This was certainly the role played by Elizabeth Kane, a non-believer touring through the Salt Lake Basin in the early 1870s. She had expected to find neglect and despair with the Mormon households she visited, and she actively sought out evidence that polygamy was enslaving women. Instead, she found similarity to her own life: At one stop she met a woman with a tidy house (including a prominently displayed Bible), and had to admit grudgingly that the woman “appeared to be . . . happy and contented.” In her first Mormon Church meeting, Kane searched for the “hopeless, dissatisfied, worn expressions” on the women’s faces that others had led her to expect; instead, she noted that Mormons looked much like any other rural congregation she had encountered.

By the time statehood arrived in Utah, Mormons were ready for America, and they had the skills to meet the challenge of—if not a 24-hour news cycle, then certainly the pace of the various dailies that graced newsstands in 1900. And most Saints met the challenge of Mormon citizenship gladly, knowing that it provided both a measure of security for their own families and community as well as an opportunity to spread their religious message to places that previously had been blocked, if not entirely closed to them. It was in that moment of arrival on the American political scene that the peculiar talents of an oppressed religious community became useful in another sense: the Saints had learned to live with the gaze of the world upon them, and that self-consciousness would become an ally in their campaign to assimilate, to function simultaneously as Mormons and as American citizens.