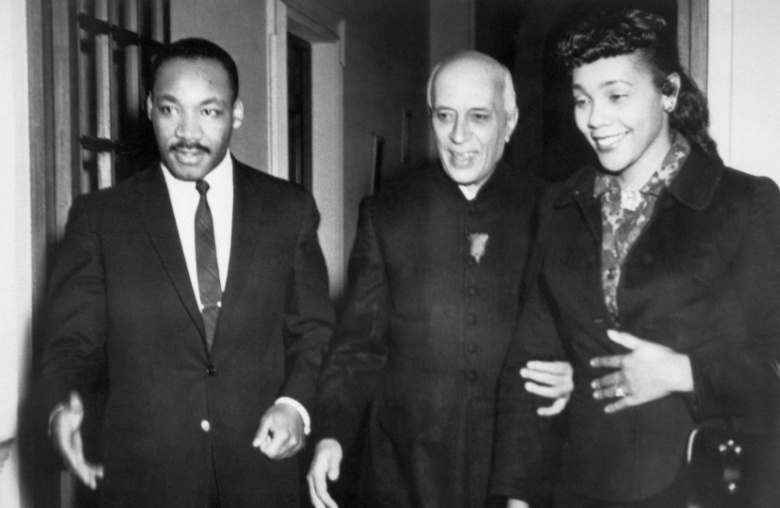

Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru (C) is flanked by his guests, American civil rights leader Dr. Martin Luther King (L) and wife Coretta Scott King during a one-month visit to India at the invitation of the Gandhi Peace Foundation in 1959. (Bettmann/Getty)

“The shape of the world does not permit us the luxury of an anemic democracy,” Martin Luther King, Jr. once stated. Nonviolence, he understood, has never been about the absence of force. It has always been about getting to the negotiating table without massive death and destruction as we see around the globe today. To build a stronger democratic coalition among the world’s people, we must all be equally outraged by the horror of Russian imperialism in Ukraine while recognizing the racism that persons of African descent have faced while attempting to escape the perils of war. While looking abroad, we must also look at home at the violence exercised by sick young men filled with white supremacist ideology. Democratic struggles are never about one kind of innocent victim, one kind of refugee, or one archetypical portrayal of public worthiness. A robust democratic understanding must link various struggles around the globe.

In his own time, Martin Luther King, Jr. understood this link. His global ministry calls us to see that the long-lasting false myths of racial superiority and hierarchy must not be given sanction anywhere. King’s vision was for us to create a better democratic majority through protest and negotiations. He believed this because democratic freedom struggles for the freedom of the self and of nations does not belong any one persuasion, but to the people of the world in every locale.

King’s 13-year political ministry was on the global stage from the outset. He opened his first speech on Dec. 5, 1955 at the Holt Street Baptist Church in Montgomery, Ala., with this challenge:

We are here this evening for serious business. We are here in a general sense because first and foremost we are American citizens and we are determined to apply our citizenship to the fullness of its meaning. We are here also because of our love for democracy, because of our deep-seated belief that democracy transformed from thin paper to thick action is the greatest form of government on earth.

King recognized that he had been shaped by global forces commencing with the 1917 Russian Revolution, the 90-year Independence Movement within India, the United States’ entry into WWII, the rising African independence movements, and the ever-mutable anti-communist ideology as articulated in the militarism of the Truman Doctrine. King’s rise in the putative capital of the failed Confederate States of America, paralleled the political defeats of the African National Congress (ANC) with Nelson Mandela and his cohort being put on trial for treason by white South African nationalists in 1956.

King, alongside his band of black middle-class–clergy, college students, lawyers, small business proprietors, and blue-collar workers, barely avoided the fate of ANC leaders. Many Southern state politicians and administrative leaders intended to silence democratic protest through show trials and jailing. Even though King and his cohorts avoided life sentences such as the ANC leaders received, they still paid a heavy toll in terms of the trauma and vicious griefs caused by arsons, assassinations, bombings, murders, and surveillance.

Throughout King’s undergraduate and graduate years, he and his generation had been educated that they were a part of a global matrix that W.E.B. DuBois described in 1901 as, “the problem of the color line; the relation of the darker to the lighter races of men in Asia and Africa, and America and the islands of the sea.” DuBois’s view would be further refined by the likes of anthropologist Eslanda Goode Robeson in her 1945 trailblazing book African Journey and her subsequent public lectures within black communities. She stressed the importance of knowledge about and from Africa in Black efforts to build political-esteem and combat racism. Following India’s lead, African, Asian, the Caribbean, and Central and South America would create angst in the world order dominated by Europeans as Richard Wright described in his travelogue Color Curtain, which documented the Bandung Conference held in Indonesia in April of 1955. King’s maturation as a thinker developed as Algeria, Cuba, the Gold Coast, and Vietnam emerged as revolutionary catalysts for ending colonialism and economic exploitation in their respective parts of the world.

As an academically trained theologian, none of this was a part of King’s curriculum. That Anglo-Eurocentric and male-centric curriculum privileged thinkers such as Aristotle, Augustine, Barth, Bruner, Hegel, Kant, Niebuhr, Plato, Schleiermacher, and Tillich. However, outside of his formal academic life, King interrogated Karl Marx’s economic determinism and engaged the world of Black writers and intellectuals from James Baldwin, Ralph Ellison, Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston, and Ann Petry. This engagement extended to the sounds of musicians like Davis, Ellington, Gillespie, Parker, Roach, Weston, and Williams; all of them, in some fashion, theorized musically about the world differently than the prescribed norms. Black artists were forcing an aesthetic reordering of black subjectivity and refashioning what democracy looked like as a global force, not just an Anglo-European one.

These nationalistic revolutionary forces in politics and culture had righteous agendas. They were in keeping with the United States’ own revolutionary tradition and its most sacred civil document, the Declaration of Independence. However, the U.S. military and foreign policy bureaucracy opposed the claims that the peoples of Africa, Asia, the Caribbean, Oceania, and South America were global democratic equals and partners. Entrenched forces within the political economy were steeped in racist mythologies that justified Anglo-European superiority and capitalist exploitation. In 1950s America, a world rife with McCarthyism, the most ambitious Southern politicians used anti-communist political rhetoric as a hammer to bludgeon conformity while giving comfort to non-elites through racist fearmongering. When we look back on the time of King’s emergence as a spokesperson for the civil rights protests, we can see that it was a hopeful time, but also a dangerous path to challenging the ruling order.

At 26 years of age, King was thrust into the global and U.S. media limelight. Using his position, he tried to teach his congregants and the people where they positioned themselves in the global democratic struggle. Using his independent base as a Baptist clergy to counterattack the hegemonic order, he drew upon a theological imperative, one that then guided most of the American population at a point when recorded church and synagogue attendance peaked. He spoke to them in relatable terms that they could understand and be mobilized. “And you know, my friends,” King colloquially offered, “there comes a time when people get tired of being trampled over by the iron feet of oppression.”

This is then how we must understand King’s earliest liberationist rhetoric. His people, the ones in Montgomery, were in a relationship to and had affinities with many people around the globe in their shared concerns over the ways the “iron feet of oppression” are exercised using a combination of fears, legalities, and violent repression.

Thinking about King’s Holt Street speech brings me full circle to contemporary times as I try to understand this most anti-democratic era, one not seen since the 1930s as the clouds of World War II loomed on the horizon. Do we see ourselves and our struggles for personal liberation in affinity with others around the globe? Is it possible to have a rhetoric of liberation that gives us commonality, or must our specific grievances dominate where none of us gain and everyone loses the right to speak? Is it even possible to name and organize around our shared existential crisis as the human species in the era of climate change?

Here, I am not suggesting a false consensus like the ones corporate America tried to create in the 1950s through slogans like the “American way” or “In God We Trust.” Can we have a rhetoric that analyzes, criticizes, and more importantly empowers a commonality to enact a powerful democratic agenda, one creating governmental transparency and just laws concerning the viability of the human species within a political economy that is planetarily beneficent? Can religiously thoughtful people serve as a catalyst to the pious proletariat and the cultural elites alike as we protest and politick to establish realizable democratic agendas at our local, national, and global levels?

As I argue in Letters to Martin: Meditations on Democracy in Black America, we must hold onto and build a democratic faith, a faith born of Black American struggle, a faith that democracy principally dignifies communities and persons alike. This faith, as King offered, is essential to our well-being as we face existential and planetary challenges that are rushing towards us. Today, more than ever, we must summon the courage to exercise a democratic faith, even as state repression continues to loom at home and abroad. We must continue to wage our democratic protest out of faith that a new future can be born.

Randal Maurice Jelks is Professor of American Studies and African and African American Studies at the University of Kansas. Jelks is an author, documentary film producer, and scholar, as well as Presbyterian (USA) clergy. He is the author of four books: African Americans in the Furniture City: The Struggle for Civil Rights Struggle in Grand Rapids, Benjamin Elijah Mays, Schoolmaster of the Movement: A Biography, Faith and Struggle in the Lives of Four African Americans: Ethel Waters, Mary Lou Williams, Eldridge Cleaver, and Muhammad Ali and Letters to Martin: Meditations on Democracy in Black America.