(AP Photo/John Minchillo)

From a global pandemic and nationwide protests to a contested presidential election, this year seems tailor-made to expose America’s partisan fault lines. Those hoping for a blue or red wave to unite the country on election night were undoubtedly disappointed. What the returns revealed instead was a divided electorate.

Even before the election results underscored America’s political gulf, Justice Amy Coney Barrett and her faith became something of a national Rorschach test for where Americans line up on the partisan spectrum. Some viewed Barrett’s Catholicism, and her involvement with the charismatic Christian community, People of Praise, as tantamount to Margaret Atwood’s dystopian novel, The Handmaid’s Tale. For others, Barrett’s faith was evidence of her character and integrity—a signal that she’d live up to her oath to “impartially discharge the duties of the office.”

What explains this divergence?

The data suggest that our national divide is deeper than just knee-jerk partisanship—it involves a confluence of religio-geographic trends in the United States that all but guarantee the kind of political gridlock we saw manifest this month at the ballot box. The United States is not a purely secular nation—nor is it a fully religious one. The country stands out among its international peers as distinctly balanced. And acknowledging this reality may be the first step to burying the country’s cultural weapons of war and embracing a posture of greater political pluralism and cooperation.

According to our recent survey report sponsored by the Wheatley Institution, a non-partisan research center at Brigham Young University, slightly less than one third of the U.S. population is deeply religious, frequently attending church services or engaging in other religious activities in their homes. Another third is fully secular, never participating in any sort of religious practice, whether it’s prayer, reading holy writ, or attending services. Meanwhile, a final third of Americans are nominally religious—attending services infrequently or engaging in other practices with varying levels of devotion.

These findings align with the 2020 National Religion and Spirituality Survey from the National Opinion Research Center as well as findings from the Pew Research Center, which estimates that roughly a quarter of American adults today are religiously unaffiliated.

The story of secularism’s rise is well-documented. “From 1981 to 2007, the United States ranked as one of the world’s more religious countries, with religiosity levels changing very little,” notes political scientist Ronald Inglehart in Foreign Affairs. “Since then, the United States has shown the largest move away from religion of any country for which we have data.” The Atlantic’s Derek Thompson similarly notes the rapid ballooning of the religiously unaffiliated, tracing its relative size from around 6 percent of the U.S. population in 1991 to more than a quarter today.

So, what happened?

There’s no simple answer. And, certainly, people stop affiliating with their religious tradition for many reasons. However, sociologists Michael Hout and Claude Fischer have published research suggesting that an aversion to the religious right’s involvement in politics throughout the 1990s (and beyond) may have influenced the decision of self-identified moderates and liberals to disaffiliate from religious institutions during this period.

“Organized religion,” they write in their 2014 study, “gained influence by espousing a conservative social agenda that led liberals and young people who already had weak attachment to organized religion to drop that identification.” The scholars note a causal link between the religious right’s entrance into public conservativism and disaffiliation among certain pockets of the population: “Political liberals and moderates who seldom or never attended services quit expressing a religious preference when survey interviewers asked about it.”

These findings are significant, but they don’t tell the full story of American faith in the twenty-first century. Much like the bifurcated reaction to Amy Coney Barrett, the same trends that seem to push some toward secularism may also help crystalize faith in others. Indeed, even as the nation is becoming more secular, in another sense, it’s also becoming more religious as well.

For example, a 2017 study from Indiana University’s Landon Schnabel and Harvard’s Sean Bock suggests that “intense religion” has persisted even as more “moderate religion” has seen declines. In other words, ascendent secularism is accompanied by a deepening of religious intensity. Speaking to The Washington Post, Schnabel compared this phenomenon to a “container getting smaller, but more concentrated.” So, yes, the steady stream of cable news chyrons on waning religious affiliation are accurate (the religious landscape is shifting) but the real story is more complicated.

The fact is that the highly religious in America haven’t gone away. They’ve remained steady as a percentage of the population, which means their overall numbers have grown with the population and their higher-than-average fertility patterns are one sign that the trend probably won’t reverse. Thus, those anticipating a full conquest of secularism in the United States shouldn’t hold their breath—neither should those rooting for a modern-day Great Awakening.

It may be that recognizing the nation’s religious and secular demographics as both stable and balanced could broker the kind of détente that recognizes cooperation and the search for genuine understanding as a productive path forward.

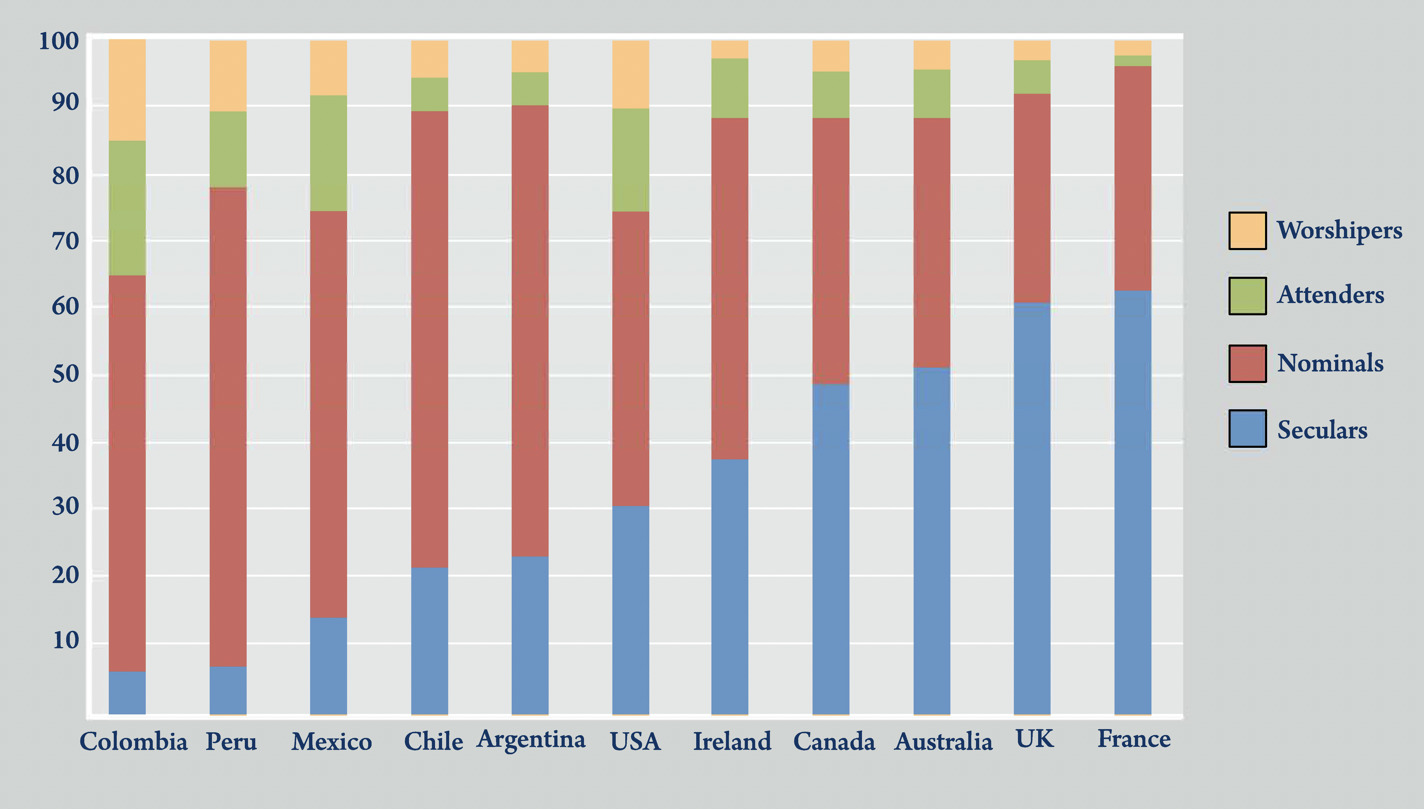

Pluralism, after all, has always been what makes America exceptional on the world stage. In our report, we analyzed data from more than 16,000 survey participants in eleven countries, looking specifically at how religion in public life varies across populations. In Latin American nations like Columbia and Peru, most respondents were both religiously affiliated and active in their faith. As you would expect, in European countries like France or the United Kingdom, religious affiliation and participation were much lower. Whereas religion was once predominant in these nations, today, secularism reigns.

The United States, meanwhile, stands out for its unique demographic mix of both seculars and the highly religious. Of the eleven countries analyzed, only in the United States do these two groups have to deal with each other on somewhat equal grounds.

Specifically, we estimate that there are a little more than 100 million American seculars and about 85 million Americans who might be considered highly religious. In other words, there are more seculars in the United States than there are people in all of the Nordic countries combined plus Belgium, the Netherlands, Australia, Austria, and Switzerland. Likewise, the church-attending population of the United States is larger than the combined populations of Chile, Venezuela, Ecuador, Bolivia, Paraguay, and Uruguay.

That’s a lot of seculars. And that’s a lot of religionists. So, it’s easy to see why one side or the other might feel like they own the country and they should control the nation’s levers of political power. An October poll showed that Christians, particularly white evangelicals, supported Donald Trump by a very wide margin (78 percent) whereas atheists and agnostics supported Biden by an even larger margin (83 percent).

Seculars and religionists may share this much in common: a mutual fear (and misunderstanding) of the other. This idea explains why they often fight so hard to gain and maintain political advantage. The phenomenon is also likely exacerbated by geographical segregation. Seculars often live on the coasts or in other urban settings, while religionists are more commonly found in the rural South and Midwest. According to a 2017 survey from The Washington Post-Kaiser Family Foundation, fully 78 percent of rural Republicans said, “Christian values are under siege.” If these geographically separated groups bump into each other, it’s usually through the less-than-humanizing lens of social media.

With these interests so evenly spread, knowledge of the nation’s demographic balance can’t help but prompt seculars and religionists to see the culture wars as a battle with little prospect of a full victory. But, given the current political environment, moving from an acknowledgment of demographic realities to actual political cooperation may be asking for a miracle of biblical proportions. And yet, at least we know that there are many Americans who might be willing to pray for one.

Spencer James, Hal Boyd and Jason Carroll are faculty members in Brigham Young University’s School of Family Life. They are each affiliated with the Wheatley Institution.