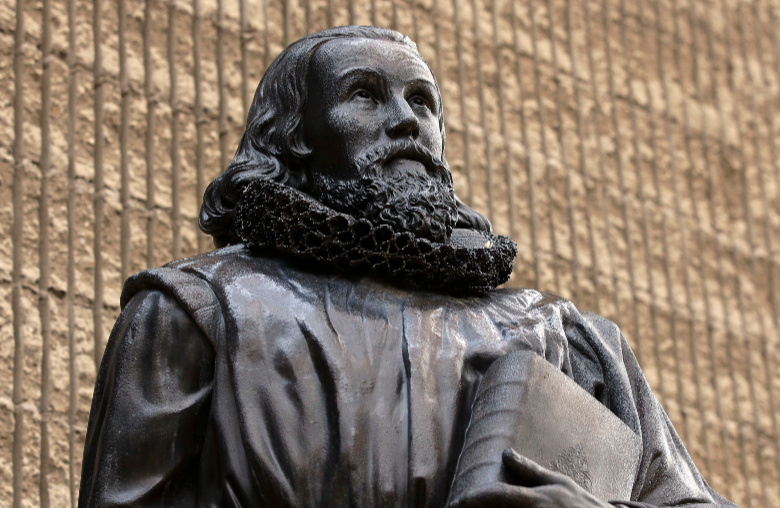

(AP/Steven Senne) A nineteenth-century bronze statue of John Winthrop, by sculptor Richard Saltonstall Greenough, stands outside the First Church in Boston.

What is the origin of America?

Ask that question systematically to more than 2,000 people, and a wide variety of answers will arise. Most focus on the founding era of the United States: the Declaration of Independence, the American Revolution, and the Constitution. Others turn to the colonial days observing that “America” existed long before the nation began. Some dwell on the Native Americans—the first people on the soil of the Americas. Others focus more on the arrival of Europeans. Amerigo Vespucci gets mentioned. The coming of Columbus. Jamestown, Captain Smith, Pocahontas. So many possible answers, so many different times and places to begin. And always, in the midst of these responses, one answer rises among the rest: Pilgrim Landing, Plymouth Rock, and the Puritans.

The question of American origins, of course, has no real answer. People can argue for their choice, but such debates tell us more about how they view America today than how “America” actually began. In that sense, historical origin stories function primarily as present-day descriptions. Each answer defines what a person means by America. Beginning with Native Americans, for example, suggests a story of chronological priority untethered to modern political boundaries: “America” is all the territory from the Bering Strait to the bottom of Argentina, and it includes all the people who have ever lived and moved and had their being on these lands. It is a long story, a tale teeming with diversity. Rather than beginning something new, Europeans stumble onto well-established nations and civilizations, disrupting traditional patterns and forms of life, adding to the mix, changing and reshaping an “America” that existed long before them.

Answers that emphasize the Revolutionary era, meanwhile, define America much more narrowly. Such responses focus on one particular nation coming into being at one particular time. Even here, however, the distinctions can be quite telling. Does “America” start with a fundamental statement of principles (the Declaration of Independence), a bloody war (the American Revolution), or the eventual establishment of a mostly stable government (the Constitution)? No doubt, most people see these answers as related, but the specific responses embed much different accounts of what makes America America after all.

When respondents point to Jamestown, meanwhile, a new element enters the picture. Jamestown is the first permanent English settlement in what would later become the United States. “America,” as a result, is a nation that blossoms forth from English roots. Jamestown outweighs and overshadows all other potential nationalities, ethnicities, races, immigrants, and colonial experiments, along with all their consequences and contributions. Few people, for example, remember that the Spanish established St. Augustine in Florida in 1565, more than four decades before the English came to Virginia. The French also came earlier than the English, beginning explorations in the sixteenth century and establishing Quebec in 1608, then pushing into what is now the Midwest and down the Mississippi. Around the same time, the Dutch headed up the Hudson. Africans were brought to Virginia in 1619. As often as I ask the question in surveys, however, no one ever mentions Spanish, French, Dutch, African, or any other national, ethnic, or racial roots.

And then, of course, there are the Pilgrims. This year marks 400 years since they stepped across Plymouth Rock, as the story goes. The Mayflower arrived in December of 1620 on the shores of present-day Massachusetts. But why do we remember that moment so much more than all the rest? On the face of it, their appearance as an origin story makes no sense. They were not the first people here, nor the first Europeans here, nor the first English here, nor did they establish a new and separate nation. What possible claim can they have to beginning the story of America?

Here, the answer focuses specifically on ideas and principles. Pilgrims surface as an origin because, we are told, they were the first ones—the only ones—who came in search of something better, something nobler, something different. They set sail for civil and religious liberty. They established democracy. They came to worship God. However one defines it, the Pilgrims arrived with a principle, and that principle, we are led to believe, is what has defined “America” ever since. If origin stories are present-day definitions cast back onto history, then the Pilgrims and Puritans have historically enabled Americans to define their nation not as the outcome of events, but as the fruition of ideals.

For many years now, such a story of America has been supported by one particular phrase: the declaration that we are a “city on a hill.” When politicians and scholars first began calling the United States a “city on a hill,” they pointed to the place of these words in “A Model of Christian Charity,” a sermon supposedly preached aboard the Arbella by John Winthrop, the first governor of Massachusetts Bay, as he and his Puritan followers sailed to New England. In that moment, in that sermon (we have been told), Winthrop opened the story of America. He called on us to serve as a beacon of liberty, chosen by God to spread the benefits of self-government, religious liberty, and free enterprise to the entire watching world. Invoking the “Sermon on the Mount,” where Jesus uses the metaphor to describe his followers (Matthew 5:14), Winthrop declared, “For wee must consider that we shall be as a city upon a hill. The eyes of all people are upon us.” Ignoring the scriptural basis for this proclamation, President Ronald Reagan explained in his 1989 “Farewell Address to the Nation” that “the phrase comes from John Winthrop, who wrote it to describe the America he imagined. What he imagined was important because he was an early Pilgrim, an early freedom man.” The significance of Winthrop’s statement, in other words, has everything to do with its timing—with the “fact” that Winthrop made this statement at the beginning of America, defining its identity and purpose ever since.

Because Winthrop’s sermon has so often been said to open the story of America, pundits, politicians, commentators and scholars have often found that they cannot avoid it. “A Model of Christian Charity” has become fundamental to the meaning of America. The presumed significance of Winthrop’s sermon has been reinforced by publishing it in anthologies, teaching it in classrooms, and invoking it in speeches. “A Model of Christian Charity” has become so central to American traditions that one scholar has pronounced it as “a kind of Ur-text of American literature,” another has declared it the “cultural key text” of the nation, and still another called it the “best sermon” of the millennium.

Yet Winthrop’s sermon came to fame only recently. It is, in many respects, a product of the Cold War. In the 1950s, a widespread and worried search for the meaning of America turned increasingly to “A Model of Christian Charity” as the answer. According to the prominent scholar Perry Miller, who taught at Harvard from 1931 to 1963, Winthrop’s sermon best defined the ideals and principles America has always represented. From Miller, the story spread, and soon the words of Winthrop found their way into the speeches of American presidents. Yet before the Cold War began, no politician and hardly any scholar had ever bothered with Winthrop’s sermon at all.

Not only did most scholars and politicians ignore Winthrop’s text, so did the Puritans themselves. Someone should have told them that they were listening to the best sermon of the millennium; maybe then they would have taken note. As it stands, hardly anyone in the seventeenth century gave Winthrop’s sermon a second thought. It was never printed or published in either England or America. No one jotted down in their diaries the day Winthrop delivered “A Model of Christian Charity.” Even Winthrop, who diligently kept a diary from the day he left England, never mentions having given it.

Perhaps the settlers had other concerns. Maybe it failed to strike a chord. Perhaps the sermon seemed a little commonplace, a bit cliché. Maybe it was never delivered at all. Whatever the reason, it seems clear that the existence of “A Model of Christian Charity” in the seventeenth century went almost completely unknown. The only mention of it that exists comes from a letter penned in the 1640s requesting a copy of “the Model of Charity.” One person seemed to know of Winthrop’s sermon, but that person was in slim company. From the writing of this letter in the 1640s until the printing of Winthrop’s sermon in 1838—for almost two hundred years—no one ever mentions Winthrop’s text again. The supposed foundation of the nation, the document fundamental to the meaning of America, the best sermon of the millennium, was nothing special in its day.

But even if Winthrop had been heard, for whom did he speak? For one thing, Winthrop was no “early Pilgrim,” as Reagan called him. Winthrop was in fact a Puritan, the leader of a separate group that came a decade later than the Pilgrims and had a different colony with distinct views of religion and politics. Blending him with the Pilgrims was expedient for Reagan and others, but it meshed into one origin what were in fact separate migrations and settlements.

Even among the Puritans, however, it is not entirely clear for whom or to whom Winthrop spoke. Certainly his voice resonated with some, especially with many ministers and magistrates in power. But what about the population more broadly? Just how “Puritan” were the English who came? When later Americans began to cast Pilgrims and Puritans as the origin of America, they not only blended together two separate groups of people; they also formed in American cultural memory a like-minded mass of religious zealots all declaring allegiance to the same protocols, all backing the same beliefs. Some did. Others didn’t. Many worshipped diligently, kept diaries, respected leaders, and spent their days trying to draw ever closer to God. Others thought little of God, went to church because they had to, and spent their lives in pursuit of land, money, power, and fame. More than 10,000 people migrated in the first decade, 20,000 by the second decade. That many people can never be the same. For an origin story to emerge from this massive migration, many in that mass would have to be ignored.

Even more to the point, in order to create a coherent story of national origins serviceable to twentieth and twenty-first-century politicians, early America would have to be flattened. Origin stories of the nation notoriously neglect the mixed motivations, lives, and societies spread across many different peoples living on many different lands. Using the “Pilgrims” as the opening of America wipes history clean of all the teeming cultures, contestations, and confusions that make it rich.

How did this happen? When did Pilgrims and Puritans come to be seen as the foundation of the entire United States? Who did the labor of making this story stick? And why did one particular sermon—delivered in 1630 and promptly forgotten, printed in 1838 and immediately ignored—come to stand as the fundamental document of American history and literature?

These are the questions I set out to answer. When I started writing about this topic several years ago, I thought it would be a fairly straightforward task to follow the life story of a single text across its many years. But it turns out the full biography of Winthrop’s “city on a hill” sermon involves two stories, not one. The first focuses on the text itself: when it was delivered, what it meant in its own day, how it was copied down, why it was lost, and what enabled it to be discovered, printed, publicized, and eventually politicized in our modern day. The second story follows the Pilgrims and Puritans into and through American culture, asking how they have been remembered and commemorated from one generation to the next. Neither tale stands without the other. For it required the creation and assertion of Pilgrim and Puritan origins to make Winthrop’s sermon wield political might. These stories arose together—a history of the Pilgrims in American culture, and a rags-to-riches biography of one long-lost and now-famous text, John Winthrop’s 1630 sermon, “A Model of Christian Charity.”

Abram Van Engen is associate professor of English at Washington University in St. Louis, where he is also a faculty affiliate at the John C. Danforth Center on Religion and Politics, which publishes this journal. He is the author of City on a Hill: A History of American Exceptionalism, from which this excerpt was adapted.

From City on a Hill: A History of American Exceptionalism by Abram C. Van Engen. Published by Yale University Press in February 2020. Reproduced by permission.