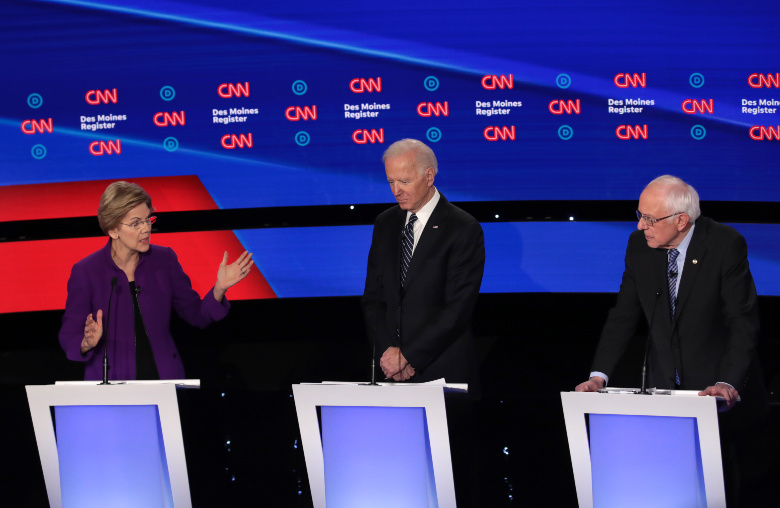

(Scott Olson/Getty) Sen. Elizabeth Warren speaks while former Vice President Joe Biden and Sen. Bernie Sanders listen at the Democratic presidential primary debate in Des Moines, Iowa.

In January, during the last Democratic debate before the Iowa caucuses, the candidates began the night with an extended conversation about foreign policy—a topic that had gotten short-shrift on earlier debate stages. The recent killing of Iranian General Qasem Soleimani at President Trump’s orders has escalated the tension between Iran and the United States, putting international affairs into the spotlight for the would-be commanders-in-chief.

In Iowa, Pete Buttigieg touted his military experience; Joe Biden pointed to his time as vice president in the Obama White House. The progressive frontrunners on the stage—Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders—tacked to the left. Sanders reminded viewers he voted against the war in Iraq, and he emphasized international coalitions, echoing a campaign email which said that he would offer voters a “different vision for how we exercise American power: one that is not demonstrated by our ability to blow things up, but by our ability to bring countries together.” Warren, in the Senate since 2013, took a hard line, recommending to pull combat troops out of the region entirely, which Biden seemed to dismiss as unrealistic.

For all of their success addressing domestic issues in moral terms, Sanders and Warren have often been criticized for not being realistic, and not clearly presenting a practical foreign policy in line with their progressive values. Sanders’ self-proclaimed “democratic socialist” domestic agenda and Warren’s progressive platform, aimed at regulating Wall Street and corporate power, have garnered the support of millions of Americans, pulling the Democratic Party to the left. They often articulate a vision of economic and social justice, but on issues of foreign policy, they have been less inspiring, ceding crucial ground to moderates’ claims of realism.

The problem comes down to this: It is difficult for progressives like Sanders and Warren to present a flexible, practical foreign policy approach while adhering to their core values such as wealth equality, fair trade, peace, democracy, and human rights. After all, how can a future President Sanders or President Warren cooperate with corrupt foreign leaders if it means compromising on their moral sensibilities? How can they champion absolute truths in an international arena that demands moral relativism?

The progressive candidates this election year seem to realize how vulnerable they are to charges of hypocrisy, a tough situation that often makes them reluctant to verify firm proposals. Sanders, for one, adamantly opposed the use of U.S. tax dollars to aid the Saudis in their war in Yemen, yet when asked whether he would continue sending aid to Israel in light of their controversial relationship to Palestinians, he refused to take a definitive stance: “I’m not going to get into the specifics,” he told Benjamin Wallace-Wells of The New Yorker last April. But, Sanders cannot avoid the tough decisions that mark the administration of any president, and he cannot define his foreign policy through negation alone. In terms of positive principles and concrete proposals, the Vermont senator remains vague, mentioning military restraint, diplomacy, and some sort of indefinable idealism that he will need to sharpen for the primaries and beyond. Commentators have noted the weakness, calling into doubt Sanders’ ability to “pass the commander-in-chief test,” as Foreign Policy magazine put it.

Warren’s foreign policy has also faced criticism for being either too progressive or not progressive enough. The democratic socialist magazine Jacobin has made the latter point several times, arguing that “while Warren is not on the far right of Democratic politics on war and peace, she also is not a progressive—nor a leader—and has failed to use her powerful position on the Senate Armed Services Committee to challenge the status quo.” Warren also faces criticism from more moderate pundits who have questioned her plans to drastically reduce the defense budget and end the “forever wars” in Iraq, Syria, and Afghanistan. “Her domestically driven major announcements on the budget, troops, and trade will pull her foreign policy in a direction at odds with her more considered public utterances,” wrote Brookings fellow Thomas Wright for The Atlantic in November.

In writing my book, Spiritual Socialists, I researched the history of another progressive presidential candidate who had to walk a tightrope on foreign policy: Henry A. Wallace, the former vice president for Franklin Roosevelt who ran a failed Progressive Party bid against Harry Truman in 1948. Like Sanders and Warren, Wallace couched his foreign policy agenda in terms of cautious intervention and proactive internationalism in a time of intense global uncertainty. He staunchly defended the viability of moral values as a benchmark of international affairs. Yet he ultimately failed to alleviate voters’ fears of Soviet aggression with his plan to promote peace and play fair. Sanders and Warren can pull from the Wallace playbook to a certain extent, especially by elevating values and moral considerations to the forefront of foreign policy discussions. But, as they have learned in the 2020 campaign, they must make policy sound more practical than prophetic, a cautionary tale they can glean from Wallace’s unsuccessful campaign.

Wallace certainly presented himself as a kind of prophet, a spiritual socialist, who marshaled religious imagery of the coming Kingdom of God throughout his political career. Religious rhetoric, in his case, bolstered his calls for peace and cooperation during the developing Cold War crisis in the 1940s. At times, Warren has done the same, telling CNN last June that her “faith animates all that I do.” Sanders, however, does not typically express his progressive vision in religious terms, although he has made references to Scripture in the past. In a September 2015 speech given at Virginia’s Liberty University, the largest evangelical Christian university in the world, Sanders vindicated socialist principles as an extension of Jesus’ “golden rule,” reminding his Christian conservative audience of the simple directive given in Matthew 7:12: “So in everything, do to others what you would have them to do to you, for this sums up the law and the prophets.” “It is not very complicated,” he said.

The Golden Rule, after all, gets at the heart of what progressives such as Warren, Sanders, and Wallace back in the mid-twentieth-century seem to be saying: Treat other people and countries as we Americans expect to be treated. Respect them as human beings and not enemies, support their national sovereignty and democratic decision-making, deal in fair trade, and offer olive branches before resorting to violence. But, is the Golden Rule a firm enough foundation for a foreign policy, and can it convince voters that progressives can keep the U.S. safe amid complex international threats? That’s exactly what Henry Wallace tried to do.

Wallace, who was replaced as vice president by Harry S. Truman just before Roosevelt’s fourth inaugural and April 1945 death, peppered his 1948 presidential campaign with religious rhetoric and a call for mutual understanding and cooperation between the U.S., the Soviets, and decolonizing nations. The Progressive Party platform that Wallace ran upon also condemned free market capitalism, racism, and the American aversion to social welfare, all within the candidate’s particular religious context. Throughout his Progressive Party campaign, Wallace continued to measure policy by the ethics of the Kingdom of God, even as many of his communist followers did not believe in God or moral, democratic politics. While an increasingly anti-communist political climate in the late 1940s and the 1950s branded communism, socialism, or any “ism” of the left as a threat to the American way of life, Wallace did not change course. For better or worse, he welcomed anyone into his fold who professed at least nominal interest in social revolution, and he did so, in the vein of Warren, without closing the door completely on capitalist enterprise.

Like Bernie Sanders, Wallace was speaking of revolution—not an insurrection triggered by a violent or hasty contingent from the top-down—but a long-term vision of social cooperation and equality, cultivated from the bottom-up. Unlike Sanders, however, Wallace never shied away from invoking religious justification for his beliefs. Spiritual statesmen, he realized, could never coerce the populous to enact values of Christian love and fellowship. To the contrary, the Kingdom of God had to be made practical, springing from a source of basic need for “local welfare,” and built upon a “voluntary social discipline” among Americans who would carry out a revolution in values as “living reality.” In other words, he wanted democratic socialism practiced as a way of life, and as a religion. “I suppose the thing which I am arguing for fundamentally and eventually is a continuous, fluid, open-minded approach to reality, which at the same time is deadly in earnest,” Wallace summarized.

Whether he knew it at the time or not, Wallace had pinpointed, in that statement, the crux of a problem that would plague him for the rest of his political career. The emerging Cold War was cold comfort for Wallace, whose pleas for “one world” of brotherhood and peace amounted to little more than a faint moralizing echo across the vacuum that he accused Harry S. Truman of steadily filling with tough talk and military build-up. Running for president in 1948 as a left-liberal alternative to Truman, Wallace had a hard time translating what he called the “cloudy and vague” language of Kingdom idealism into practical policy, especially when national security seemed at stake. He discovered that moral absolutism did not dovetail with presidential pragmatism, and he ended up sounding wishy-washy when pressed for tough action. Truman won the campaign because he ran on a platform fitted for his time; Wallace lost because he ran on a platform projected for all time, the long haul of God’s will for the world.

Wallace’s “people’s revolution,” as he described it, would have taken the form of a gradual change in international relations, toward a world in which powerful nations no longer played power politics with the less fortunate. He did not promote an immediate uprising in the vein of Lenin. Neither did he favor the protectorate system of Wilson. Modernity had made the world an interdependent “neighborhood” or “human family” and only cooperation among equal partners for the general welfare could secure peace. It seemed pointless to fight and win the war, he argued, if the resulting armistice allowed “an international jungle of gangster governments” and “money-mad imperialists” to continue their “old tyranny.” Wallace included the United States among them. He urged his countrymen to seize the opportunity to set a moral example for the world in terms of race and class relations, education, and economics. “We cannot assist in binding the wounds of a war-stricken world and fail to safeguard the health of our own people,” he stated in his speech “America Tomorrow.” In other words, the revolution must begin at home before it could make a global impact.

To some critics, such as fellow democratic socialist Dwight Macdonald, Wallace’s vision “combined provincialism and internationalism in a bewildering way.” He did not understand Wallace’s intention of cultivating changes in social behavior and values from the local-level to the international arena or he simply chose to dismiss such plans as naïve, especially given Wallace’s association with communists. Wallace, however, considered his approach vital and practical. “Religion to my mind is the most practical thing in the world,” he explained. “In so saying I am not talking about church-going, or charity, or any of the other outward manifestations of what is popularly called religion. By religion I mean the force which governs the attitude of men in their inmost hearts toward God and toward their fellow men.”

Of course, Wallace lost in 1948, garnering only 8.25 percent of the vote. Given the Cold War climate, and his sidelined position as a third-party candidate, it was much easier for Truman to convince voters to contain the world rather than liberate it. Americans could not or would not take Wallace seriously as a practical politician once his associations with communists became known. However, Wallace’s failure to appeal to a wide electorate also stems from his inability to project a concrete democratic socialist framework as international policy. His abstract Golden Rule language sounded rhetorical when many voters wanted realism.

Wallace’s career helps illustrate the viability of democratic socialism in national politics; but it also tells us something about the America left and the limits of its religious rhetoric and moral claims in the realm of foreign policy. In policy debates on domestic issues, such as welfare, labor, and civil rights, socialists often gain traction by appealing to the moral and religious sensibilities of the American public. But, values-talk, whether religious or ethical, has its limits, especially when it comes to restructuring foreign affairs. Civil rights activists in the mid-twentieth-century, for instance, had much more success leveraging the Cold War contest toward reforming domestic issues of race and class than it did projecting spiritual values onto foreign policy. The road became much rougher, indeed, when attempting to convince Americans that peace, love, cooperation, and democracy should extend to international relations, especially toward perceived enemies.

Democratic socialists like Wallace insisted that Americans must adhere to a Golden Rule standard by allowing communities abroad to determine their own way forward, toward peace and cooperation, from the bottom up, something that Sanders and Warren currently echo. When asked about the crisis in Venezuela, Warren, for example, stated, “Instead of reckless threats of military action or sanctions that hurt those in need, we should be taking real steps to support the Venezuelan people.” When faced with these tough choices in the presidency, however, she and Sanders must make moral action practical, and that remains the primary challenge for all progressives and socialists advancing their values in the world.

Vaneesa Cook is a historian, professor, and freelance writer in Wisconsin. Her book Spiritual Socialists: Religion and the American Left, from which this excerpt is adapted, is available through the University of Pennsylvania Press. Follow her @CookVaneesa.