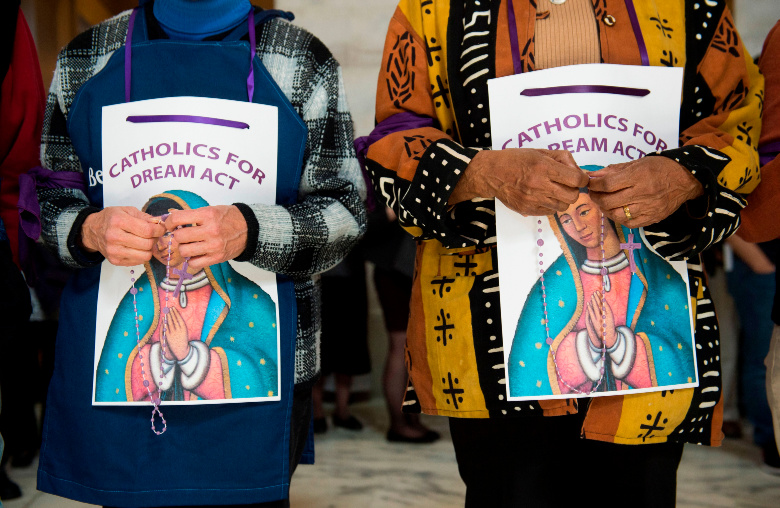

(Saul Loeb/AFP/Getty)

Readers of different religious traditions, and even those within the same tradition, may read sacred Scripture in radically divergent ways. Among the most pronounced ways this occurs is in the common refrains that religious immigration activists tend to cite. The Hebrew Bible directs adherents to watch over the ger, a term that alludes to a permanent resident or a convert and is often defined imperfectly as “stranger.” The New Testament depicts Jesus as a refugee, and the Quran directs the religious to care for both the wayfarer (aabir sabeel) and the homeless (ibn sabeel). These religious values motivate many to advocate for refugees and would-be immigrants, while many others understand their religious mandate differently.

Exegetical variety aside, experts and nonprofit leaders say that religious activists have rallied of late in response to the president’s immigration policy and rhetoric. Since President Donald Trump’s election, immigration activists have demonstrated a “new energy” and a “new level of urgency,” even though they were concerned about high levels of immigrant deportation under President Barack Obama, says Grace Yukich, associate professor of sociology at Quinnipiac University in Hamden, Connecticut, and author of One Family Under God: Immigration Politics and Progressive Religion in America.

“The anti-immigrant rhetoric during Trump’s presidential campaign frightened immigrants and their allies, including many faith-based activists, who saw such rhetoric as antithetical to their religious traditions’ calls to welcome the stranger,” Yukich says. The activists are concerned about what they interpret as White House efforts to curb the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program (DACA), to reduce both legal and illegal immigration, and to curb the scope of the Fourteenth Amendment. Activists are also concerned about separation of families on the border, targeting of undocumented immigrants without criminal records, and the tragic incidents of immigrant children who have died within U.S. custody. The activists worry both about the immigrants and “the moral and spiritual health of a nation that often treats immigrants in cruel and inhumane ways,” Yukich says.

Mark Hetfield, president and chief executive officer of HIAS, has seen more American Jewish passion for welcoming refugees and asylum seekers than he has observed in decades. (HIAS was founded in 1881 as the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society.) “They want to volunteer to welcome them, to set them up in new homes and new communities, and to help them navigate our Byzantine and often vicious legal process,” he says. “Unfortunately, with the Trump administration’s allowing the fewest number of refugees in the 40-year history of the program, and with the ‘remain in Mexico’ policy, volunteer opportunities are increasingly scarce. Consequently, we’ve facilitated more advocacy opportunities to change these policies.”

More than 2,000 rabbis and hundreds of congregations have formally committed to work with HIAS to support welcoming refugees, and HIAS helped organize more than 100 meetings between constituents and their congressional representatives this summer. “The global refugee crisis of 2015, and then, just before the Jewish high holidays, the photograph of the lifeless body of 3-year-old Alan Kurdi washed up on the beach in Turkey, woke up our entire community, and they’ve been actively engaged in welcoming refugees ever since on a scale we haven’t seen since the late 1980 and the Soviet Jewry movement,” Hetfield says. “The big difference today is that they are not welcoming refugees who are Jews, but welcoming refugees as Jews.”

Religious activists are helping immigrants by providing legal services along the border, raising money to help immigrants and their families, and offering sanctuary to those at risk for deportation through the New Sanctuary Movement, which offers “sacred resistance,” Quinnipiac University’s Yukich says. Activists are also educating communities about immigration policies and collaborating with groups like No More Deaths, an Arizona-based organization that provides water and other necessities to immigrants and is part of the Unitarian Universalist Church of Tucson.

When Joan Rosenhauer, executive director of Jesuit Refugee Service/USA, thinks about her group’s humanitarian work, she turns to the New Testament. “The fact that the very Son of God was a refugee serves to call us to see the face of Christ in all those who are forced to flee,” she says. (While Gospel stories from Jesus’ childhood are rare, one has his family crossing a national border, fleeing King Herod-endorsed infanticide in Bethlehem for Egypt.) Jesus preached that when one visits the imprisoned or feeds the hungry that one is visiting and feeding God, Rosenhauer says.

Jesuit Refugee Services, which was founded in 1980 and is based in Rome, supports refugees in more than 50 countries. Its activities include creating safe spaces for children within refugee camps, running schools, training refugees to teach and to launch businesses, providing food and hygienic supplies, and offering pastoral and religious support to those in U.S. detention hoping to immigrate. On the U.S. southern border in particular, the U.S. chapter operates a program where chaplains provide pastoral and religious assistance to non-citizens in five detention centers operated by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security. (Rosenhauer has visited the centers in El Paso, Texas, and in Florence, Arizona. The others are in Batavia, New York; Los Fresnos, Texas; and Miami.)

In 2018, Jesuit Refugee Service activists distributed religious materials, provided religious services through volunteer faith leaders, and offered stress management classes and psychosocial support to 10,453 migrants through this program, Rosenhauer says. The Mexican chapter of Jesuit Refugee Service also collaborates with other Jesuit organizations to help migrants with legal and psychological support. “Many of our donors support our work with displaced people where it is most needed,” Rosenhauer says. “We see a lot of generosity among Americans toward people who have fled their homes, but it is not exclusively focused on the U.S. border.”

Catholics aren’t monolithic in their views, including on immigration reform, according to PRRI data. More than 60 percent of Catholics in New York City and 70 percent of Catholics in Washington, D.C., believe immigrants strengthen the country with their hard work and talents. In Philadelphia, on the other hand, 45 percent of Catholics think immigrants take American jobs, housing, and healthcare, a 2015 PRRI survey found. But Rosenhauer has been impressed with the ways that Catholics worldwide have responded to Pope Francis’ public support for refugees. In a message released in advance of the church’s World Day of Migrants and Refugees, which was held on September 29, the pope stated that “the presence of migrants and refugees—and of vulnerable people in general—is an invitation to recover some of those essential dimensions of our Christian existence and our humanity that risk being overlooked in a prosperous society. … I invoke God’s abundant blessings upon all the world’s migrants and refugees and upon all those who accompany them on their journey.”

Not every faith group is seeing a surge in activism around immigration reform. Many members of the Orthodox Jewish community in Lakewood, New Jersey, for example, read the Torah literally and turn to Jewish teachings for guidance on all aspects of life. At the yeshiva Beth Medrash Govoha, some 6,000 men pore for many hours a day over Hebrew and Aramaic texts, and most can recite Exodus 22:20 (“Neither harass nor oppress the ‘stranger,’ for you were ‘strangers’ in Egypt”) by heart in biblical Hebrew, but they aren’t interpreting the verse, or others like it, as a mandate to jet or bus to the southern border and pitch in. Instead, members of this community (and many others) tend to see their primary religious responsibility as internal obligations to more immediate neighbors.

“Our tradition teaches us—and it is imbued through our education, both in our homes and in our Yeshivas—that people have a deep and important responsibility to care for each other’s welfare,” Rabbi Eli Steinberg says, speaking personally rather than in his capacity as Beth Medrash Govoha’s spokesman. “What it also teaches us is a system of prioritization of our efforts. We are responsible for those closest to us first: family, extended family, community.”

But other Jewish communities read the biblical texts differently. An 85-year-old rabbi was handcuffed with a plastic tie while protesting outside Philadelphia’s Immigration and Customs Enforcement office last year, even as the man, who walks with a cane, needed assistance to stand, the Jewish Telegraphic Agency reported. This past July, the Associated Press reported that a network of more than 70 synagogues nationwide has committed to supporting asylum seekers and immigrants.

Imam Omar Suleiman, the Dallas-based founder and president of the Yaqeen Institute for Islamic Research and a Southern Methodist University adjunct Islamic studies professor, was arrested at the U.S. Capitol last year for protesting the mistreatment of American-born children of undocumented immigrants, known as “Dreamers” based on never-passed congressional legislation called the DREAM Act. “Hundreds of thousands of families are being ripped apart and we need to come to a permanent solution for them,” he posted on social media at the time.

Suleiman’s activism is theologically motivated and draws upon a faith tradition in which stories of migration are hardwired into the theology. Islamic Scriptures tell of Muslim migrants fleeing violence from Mecca to both Medina and to Abyssinia, a Christian land. Abraham, Moses, and Jesus, who are also prophets in Islam, were migrants, and the Islamic calendar starts with the date of the migration from persecution. The Quran prescribes recognizing the sanctity of all sons of Adam—meaning all people—and caring for both the wayfarer and the homeless.

Islam’s teachings on the sanctity and dignity of the human being are principles that Suleiman believes and explains to the immigrants in detention that he meets. “I read Scriptures on general hardship, ease, patience, and love. I definitely use a universal language,” he says. “I have a set of Scriptures that I read … nothing that a Christian or Jew couldn’t pray to.” When he talks—and more importantly, he says, listens—to young immigrants, he is frequently asked to pray, typically for the young people’s relatives. The Quranic verses, which he translates into Spanish, include this one: “When my servant cries out to me, then I am near to him. I answer the call of every caller when they call unto me, so that they will respond to my call and believe in me. So that they will find guidance.” He adds this verse from the Quran as well: “With every hardship comes ease.”

Among American evangelical Christians, there are longstanding and deep divisions on immigration and refugees, John Fea, professor of history at Messiah College in Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania, says. Fea is the author of Believe Me: The Evangelical Road to Donald Trump. The spectrum of evangelical views on immigration range from Jim Wallis, founder and editor of Sojourners magazine and author of the 2013 op-ed “The Bible’s case for immigration reform,” and the National Association of Evangelicals on the left, to groups on the right like Evangelicals for Biblical Immigration, Fea says.

Those in the same camp as Evangelicals for Biblical Immigration largely oppose granting citizenship to American-born children of undocumented immigrants affected by the DACA program, and would like to see borders either closely defended or severely restricted, Fea says. “[They] claim that these verses are manipulated by the evangelical opponents to serve their political interests,” he says. “Most claim that these verses about welcoming the stranger do not apply to illegal immigrants, because these immigrants are breaking the law.”

The essential evangelical division here, which divides along political lines, pits Christian compassion against rule of law. “The evangelical differences on immigration have been around for several decades, but right now politics seems to be shaping everything,” Fea says. “Almost all of the evangelicals, who support Trump’s Supreme Court nominations, [and] move of the Israeli embassy to Jerusalem … also oppose all forms of illegal immigration and are fearful about the arrival of these refugees. If they do have any moral qualms or pricks of conscience about the separation of families at the border or the treatment of refugees in detention centers, they do not speak up about it.”

Many white evangelicals, he says, believe that a wall is the only solution to the problem on the southern border. “They do not want to jeopardize their access to political power, because Trump is delivering on abortion and Supreme Court justices, and other issues that are more important to them than immigration reform,” Fea says. “Evangelical Christianity in America has been divided for a long time, but the immigration debate, and Trump’s handling of it, reveals this division perhaps more than anything else.”

Menachem Wecker is a freelance journalist in Washington, D.C.