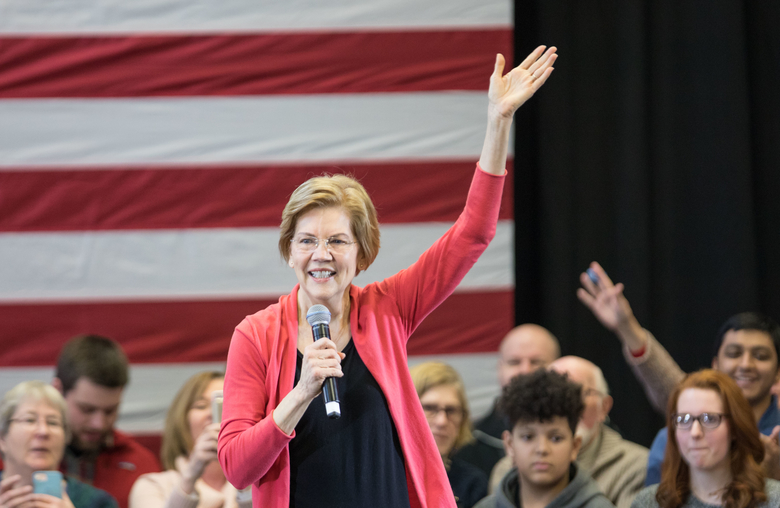

(Scott Eisen/Getty Images)

Ancient Greek had two words for time: kairos, meaning an opportune time, and chronos, meaning chronological or a set amount of time. Christian theology makes a big deal out of kairos moments. Jesus uses kairos for “time” when he declares in the Gospel of Mark: “The time is fulfilled, and the kingdom of God has come near; repent, and believe in the good news.” More recently, the Rev. William Barber took a leadership role at the Kairos Center at Union Theological Seminary in New York, from which he leads the Poor People’s Campaign: A National Call for Moral Revival.

Three years ago, I felt a kairos moment that turned out to be more chronos.

I took the subway down from Union Theological Seminary—where I was a few weeks away from finishing my Master of Divinity degree—to Hillary Clinton’s campaign headquarters in Brooklyn. After months of trying to leverage every connection I had to get a meeting, the moment finally came in April 2016. I had high expectations for the Clinton campaign’s commitment to religious outreach. After all, the candidate had spoken regularly of her political awakening coming from a church youth group trip to see MLK speak.

“Probably my great privilege as a young woman was going to hear Dr. Martin Luther King speak,” Clinton said in 2014. “I sat on the edge of my seat as this preacher challenged us to participate in the cause of justice, not to slumber while the world changed around us. And that made such an impression on me.” The lifelong Christian who spoke eloquently about her faith was running against a man who likely wouldn’t recognize Jesus even if he showed up on Page Six of the New York Post.

I sat on the edge of my seat in a conference room with senior campaign staff and made my pitch for a robust religious outreach program for the campaign. I’d spent my entire life frustrated with how the religious right dominated our public conversation about faith and politics. I felt deep in my soul that Clinton’s campaign came at the opportune time to shift this dynamic.

Sadly, it was like I was speaking in Greek to them. I gave them six specific action items to consider and never heard back. Lest you think it was just me, conversations with other advocates of Democratic faith outreach have told me they made similar pilgrimages to pitch the campaign and were rebuffed. Michael Wear, who worked on faith outreach for President Barack Obama’s administration and 2012 re-election campaign, said Clinton’s aides wanted to run a “post-Christian” campaign.

Hillary Clinton, who reportedly thought “all the time” about becoming a Methodist minister before getting into politics, ran a campaign that employed 4,200 staffers at its zenith but never employed one full-time staff person to coordinate the campaign’s religious outreach. (One full-time staffer split time between religious outreach and Irish-American outreach, while another woman was tasked with African American church outreach. Neither had significant influence on the campaign.)

While I have no desire to argue about why Hillary Clinton lost, the complete abdication of her campaign’s responsibility to engage religious values as a motivating factor for voters is vital to understanding our current context for how the chronos of the religious right drags on, and we who are part of the religious left fervently await a kairos moment.

But since I defined kairos, I think it’s also important to define our other key term here: religious left.

For me, the religious left consists of individuals and groups who are politically part of the American Left or progressive movement and also self-identify as religious, whether that’s Muslim, Jewish, Christian, Buddhist, Sikh, or any other of the myriad religious groups that make up our nation’s spiritual patchwork. “Left” is the noun, denoting those who support social and economic justice; and we’re speaking specifically about those of us on the “the Left” who are religious.

I think it’s that simple, but many people don’t. Here are the three main reasons that critics resist the term.

First, whether or not someone counts as part of the “left” is a favorite game of people on the “left” who try to out-radicalize each other. Does supporting the end of drone strikes make you a leftist? No, according to the non-interventionist left that wants to see the U.S. bring all troops home. Does supporting a pathway to citizenship for undocumented immigrants? Not for those who want to see Immigration and Customs Enforcement abolished.

Second, the term is also limited because it sets up a dichotomy of left-versus-right when the reality is that most Americans’ political views don’t fit nicely into one category. Religious leaders like the Rev. Barber bristle at the term “religious left” because they see themselves as moral leaders outside the left-right divide. Others, like the Rev. Jim Wallis of Sojourners, oppose abortion rights and distance themselves from “the left” in that regard.

And, finally, many non-religious and religious Americans shun the term “religious” being used in politics. They’re mostly white (the black church has long history of social and political activism). The theocratic tendencies of the religious right have tarnished perceptions of the good role people of faith can play in the public square while also valuing U.S. religious pluralism. Contrary to widespread assumptions about religion mixing with politics, one of the oldest advocacy groups for the separation of church and state—Americans United—has long been helmed by progressive religious leaders.

We should define an individual or group’s beliefs and politics with specificity: a “Catholic anarcho-communist,” a “gay investment banker who attends an Episcopal church on Wall Street,” or a “lifelong Republican Mormon in Utah who cares about immigrants since he was a missionary in Honduras.” These three individuals might all be members of a “Christians Against Trump” Facebook group, but they are certainly not part of an ideologically cohesive political bloc.

No term in politics is perfect, but paying attention to the “religious left” or what we might instead call “religion on the left” in all its complexity and diversity is important. For those of us who write about religion and politics, it’s about journalistic ethics. We live in a society that in our public imagination equates “religious” with “conservative” and contrasts the “religious right” with the “secular left.” But the Society of Professional Journalists’ Code of Ethics says journalists should “boldly tell the story of the diversity and magnitude of the human experience” and “seek sources whose voices we seldom hear.” This practice includes progressive people of faith, as well as religious moderates and atheist conservatives.

The religious left is receiving more attention over the past few months because 2020 Democratic candidates are talking about their faith. I’m an eternal optimist and think the kairos moment of the religious left might again be close at hand.

Mayor Pete Buttigieg of Indiana, Senator Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts, Senator Cory Booker of New Jersey, and others are generating positive media attention about Democrats getting back into the God game.

“I think it’s unfortunate [the Democratic Party] has lost touch with a religious tradition that I think can help explain and relate our values,” Buttigieg told The Washington Post. “At least in my interpretation, it helps to root [in religion] a lot of what it is we do believe in, when it comes to protecting the sick and the stranger and the poor, as well as skepticism of the wealthy and the powerful and the established.”

Booker told Religion News Service, “I think Democrats make the mistake often of ceding that territory to Republicans of faith.”

And Senator Warren practically delivered a sermon during a CNN town hall. “[Matthew 25] does not say, you just didn’t hurt anybody, and that’s good enough. No. It says, you saw something wrong. You saw somebody who was thirsty. You saw somebody who was in prison. You saw their face. You saw somebody who was hungry, and it moved you to act. I believe we are called on to act.”

This shift is hopefully the beginning of campaigns making deep investments in religious outreach, including proactively engaging religious media, hiring staff to coordinate campaign activities, traveling to religious events, and engaging religious leaders in policy discussions. These investments, which would mark an important change from 2016, mirror the two goals of all political campaigning: persuasion and turnout.

Political campaigns spend a considerable amount of energy devising compelling and unique ways to engage voters. This often takes the form of specific strategies of constituency outreach across various identities, such as Asian and Pacific Islander (AAPI), LGBTQ, veterans, and women. Within these buckets of mobilization, Democrats should stress outreach to black Christians and religious minorities. Rising religious intolerance in our country that targets black churches, synagogues, and mosques is also an opportunity for Democrats to focus on their priority of fairness and civil rights while wading more deeply into the waters of religion.

But Democrats shouldn’t limit their religious base mobilization to these groups. White Mainline Protestants and Catholics are roughly divided in their political views. According to the Pew Research Center, Catholics lean slightly Democratic (44 percent to 37 percent) and white Mainline Protestants lean slightly to the GOP (44 percent to 40 percent). Neither fits the cultural stereotype that Christians vote Republican. There are more Democratic voters who are Catholic (9.1 percent of the U.S. population) and mainline Protestant (5.9 percent) than black Protestant (5.2 percent), Jewish (1.2 percent), and Muslim (0.6).

Among these split religious communities, candidates can use the campaign art of persuasion to recruit progressive people in the pews. Eighty-three percent of Democrats believe in God, according to Pew. Living in a culture where Republicans have somehow managed to lock up God-talk makes the choice to vote or defend a vote for a Democratic candidate difficult. I’ve met countless Democrats and Independents who tell me how conflicted they feel about even bringing religion into political discussions.

Democratic candidates engaging in more religious outreach will tilt the scales to more of an equilibrium, where we see how faith inspires people across the political spectrum. It will persuade Independents and Republicans of good conscience who are sick of the immorality of President Trump’s agenda that there is a viable alternative.

And to be clear, this viability is not limited to a candidate’s personal religious beliefs—although sharing authentic convictions is always helpful—or in moderating policy stances to be more conservative socially. Religious outreach is about displaying value for the role of religion in public life by showing up and engaging religious leaders. An atheist running for president could do this just as well or better than an ordained minister running for office.

It’s an exciting time for the religious left. The 2020 candidates are engaging with religion, there are debates happening about whether the religious left is rising or just finally getting its time in the spotlight, and there are political analyses of what effect Democrats closing the “God gap” will have. I am hopeful that this time will be different.

It will take significant investments from campaigns and continued interest from the media to really change the fault lines of how we see religion in public life. But with Buttigieg, Warren, Kirsten Gillibrand, Kamala Harris, and many more candidates openly talking about the religious values that animate many voters’ progressive politics, I’m more hopeful than I was when I walked into Hillary Clinton’s campaign headquarters that this might actually be a kairos moment for the religious left.

Guthrie Graves-Fitzsimmons is the founder and editor of The Resistance Prays, a daily devotional aimed at spiritually and politically defeating Trumpism. He’s the author of a forthcoming book with Fortress Press on progressive Christianity.