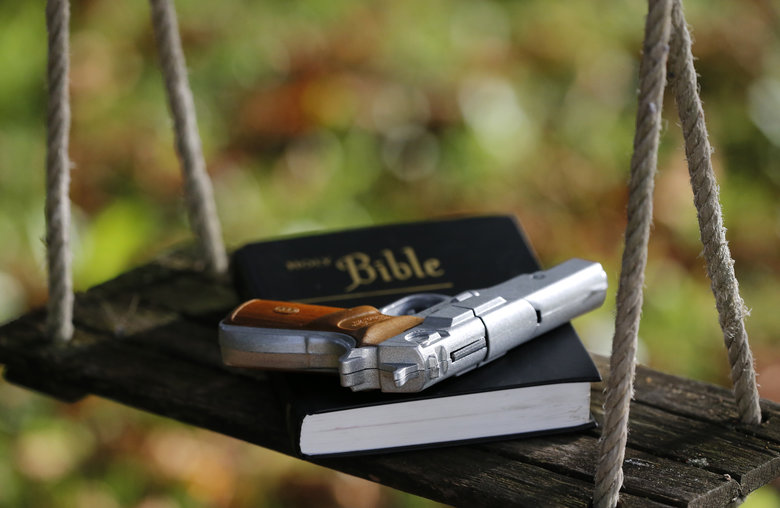

(BSIP/UIG/Getty)

The minister closed the door behind him as he entered the small office, hidden away in the U.S. Capitol building. Having run two blocks after getting the call moments before, he sat down across from the member of Congress.

“My whole life is falling apart in front of my eyes,” the congressman confessed, so emotional he had a hard time catching his breath. The clergyman knew him as a rising star. But now the politician had been caught in a scandal that would end his career. “Everything I’ve ever worked for in my life is about to fall apart,” he said. “I own a gun. I know how to use it, and I think that’s the best way for this to end.”

The Rev. Rob Schenck gets emotional as he relates this scene, describing it as “one of my most difficult pastoral encounters.” Since 1994, the native of upstate New York has led the evangelical ministry Faith and Action on Capitol Hill. “When you’re with a person in that moment, it’s literally a life-saving rescue operation,” says Schenck, age 60. “As a minister, the most important and urgent attention is to the soul. I told him, ‘Congressman, in the midst of your pain and agony and what looks like only disaster, there is hope.’” The member of Congress eventually went to counseling, according to Schenck.

A series of gun-related incidents over the past decade profoundly altered the trajectory of Schenck’s vocation. Until 2014, Schenck was perhaps best known as a prominent anti-abortion activist and for his work with Operation Rescue. Over the years, he began to see opposing gun violence as part and parcel of his pro-life work. It struck him how closely linked suicide was to gun violence. The latest available CDC figures reveal that suicide is the second leading cause of death for Americans ages 15 to 34, and nearly half of all suicides occur by firearms.

“Every human life is sacred, holy, and of inherent value,” says Schenck. “This value crosses over into anything that would artificially interrupt the process of life, from homicide to suicide to abortion to so-called euthanasia to disease.”

In the few years since Schenck first broached the topic, the conversation around firearms and suicide has not abated. On November 5 of this year, a gunman entered a small Sunday church service in Sutherland Springs, Texas—ultimately cutting short 26 lives before taking his own. Suicide rates have continued to climb. In March, Netflix released 13 Reasons Why, a serialized show about a teenage suicide, which has been criticized for romanticizing taking one’s life. And in Washington, finding a congressional majority for specific gun control measures has proved elusive, even as gun ownership has increased nationwide.

Schenck is a lifetime NRA member, saying he supports the Second Amendment. It hasn’t kept him from uncovering the issue deeper. In his own firearms training, he recalls how his Marine trainer emphasized that carrying a weapon means being ready to kill—otherwise, the weapon will be taken and used to cause harm. “So now I ask believers who conceal-carry or open-carry: ‘Who are you ready to kill today? Who will God allow you to kill today?’” Schenck says. “That’s a heavy moral question for a Christian to ask.”

His natural constituency during his four decades in ministry has been conservative Christians. What if opening people’s eyes to the ethical implications of firearms could do more than lobbying to change laws ever could?

THE SON OF A Jewish father and a mother with Catholic roots, Schenck was raised to see the connections between faith and valuing every life. Images of the Holocaust from a picture book are among his earliest memories. Schenck converted to Christianity as a teen, soon pursuing a theology degree and a career in ministry.

By the mid-1980s, Schenck increasingly focused his ministry on anti-abortion efforts. His advocacy inevitably led him to Washington, D.C., where he became a “minister in the public square—much as Jesus was in his day,” he says. His nonprofit group, Faith and Action, provides equal parts private chaplaincy to elected officials, issue advocacy, and public evangelism.

This past decade has given Schenck a broader focus. The clergyman began to notice that certain lives lost—to gun violence—were rarely discussed in some pro-life circles. In 2006, Schenck went to Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, in the immediate aftermath of five Amish schoolgirls being killed. Ten girls were shot and the gunman committed suicide.

Serving as chaplain following many such incidents, one question kept returning to Schenck: “Is there nothing we can do to put an impediment between someone with murderous thoughts and the means to efficiently and immediately carry out those intentions?”

Three years ago, filmmaker Abigail Disney was asking the same question—though with a different ideological lens. A self-described “pro-choice feminist,” Disney nonetheless admired how abortion foes spoke of the sanctity of life. Seeing a contradiction with conservatives’ views on guns, she sought out voices willing to answer tough questions. It led her to Schenck, who engaged on the issue—though he thought it risky. His Christian supporters were often gun owners, and he knew films from the Disney family got attention.

Indeed, Abigail Disney’s grandfather Roy co-founded Walt Disney Studios. Yet far from making an idealized family film, this director tells the story in all its untidy reality. The resulting documentary, The Armor of Light, recounts key events that began to change Schenck’s views, following him to an NRA convention and into difficult conversations in communities of color. The film replays deadly shootings in the Amish community and in Schenck’s D.C. neighborhood; examines the enigma of squaring pro-gun and pro-life convictions; and raises questions about race and justice.

After a modest initial roll-out at a dozen film festivals and as many colleges, The Armor of Light gained a wider audience. Church leaders screened it in 400 congregations, and PBS aired it last May to an audience of more than 100,000. It was released on Netflix last year. On October 5, the film won an Emmy for Outstanding Social Issue Documentary.

Schenck says most believers who’ve seen it praise the open dialogue on guns. Yet he’s also encountered passionate pushback, as seen in the film itself. In one scene, activist Troy Newman, president of the anti-abortion group Operation Rescue, appears in a meeting with Schenck. At first, he replies with a well-worn line about the power of good men with guns. Within seconds, emotion overtakes dialogue. “You’re living in a delusional fantasyland that you’ve created for yourself in the ivory towers of Washington, D.C.,” Newman shouts at Schenck. “You don’t live in the real world!”

Now used to hearing heated rhetoric, Schenck is not dissuaded from his mission. “The questions presented by guns and suicide are not easily and glibly answered with slogans,” he says.

WORKING FROM A SMALL row house located behind the U.S. Supreme Court, Schenck and his staff are not alone in their soul-searching. In an extensive national survey, LifeWay Research found churchgoers feel ill-equipped to deal with the issue of suicide. More than half of respondents admitted they hear more gossip in church about suicide than actual help offered to those suffering.

Dynasty Jefferson, a mental health specialist in Chantilly, Virginia, agrees that faith communities should be discussing suicide more. “It seems like people are silent about suicide until it happens—then everyone has an opinion,” she says. “The church, as well as society, needs to start a conversation about suicide and mental illnesses.”

Another resource among mental health experts comes from extensive research into how religious participation is linked to suicide prevention. Written by practicing physicians and their research team, the Handbook on Religion and Health, 2nd Edition provides a meta-analysis of peer-reviewed research on these themes. With the rise of suicide among service members, the U.S. Army recently began using insights from the handbook in hopes of saving soldiers’ lives. “Strong Bonds” retreats led by the Army chief of chaplains are intended to bolster faith and relationship skills, building on research about religion, suicide prevention, and resilience.

A top-line summary shows that religious people tend to be at lower risk of suicide than nonbelievers. However, the relationship between faith communities and risk of suicide is more complex—particularly when factoring in the reality of shame. “Being part of a church can provide support and community that benefit a person’s wellbeing,” says Jefferson, who concentrated on suicide prevention when earning her psychology degree.

The downside is some churchgoers feel social pressure to keep up appearances. “There is this notion that Christians are happy, always full of light and joy,” Jefferson says. “An individual active in church can be struggling with a mental illness or another difficult situation, and will feel the need to hide it. Shame and guilt only exacerbate the problem, preventing them from reaching out for help.”

The belief that suicide is inherently sinful can also drive people at risk deeper into self-loathing and depression. Such feelings present real dangers in faith communities without a plan for suicide prevention, which starts with broaching the topic. Counselors advocate communities listen with empathy and connect the person to appropriate resources. Evangelical authors Rick and Kay Warren, who lost their son to suicide in 2013, urge pastors and lay leaders to invest in a one-day mental health training course to be equipped in dealing with crises when they arise.

Schenck emphasizes trends showing believers have greater contentment in life and overall lesser incidence of mental health issues, but he admits they are not immune to suicide. “Certainly plenty of religious people, including Christians, experience suicidal thoughts,” he says. “Dietrich Bonhoeffer, my hero, did when he was in prison and when he was being tortured.”

He also points to the potential peril when firearms are more prevalent in a community. “A gun in the home raises the suicide risk for everyone: gun owner, spouse, and children alike,” states a 2013 Harvard Public Health article, summing up recent research.

THOUGH MASS SHOOTINGS GET more media attention, nearly two-thirds of all gun deaths in America are by suicide. Firearms require a unique public policy response compared to other threats to human life, says Schenck. “A gun is engineered to do its job, which is to kill.” It’s uniquely dangerous, he says with conviction, compared to a knife, a baseball bat, or some other object. “Combine a lethal weapon with depression, desperation, hopelessness—it makes suicide awfully easy and awfully certain.”

There are a number of known risk factors that contribute to suicidal thoughts, attempts, and completion, according to Dr. Laurel Shaler, a professor of counselor education at Liberty University. The risk factors she and others cite include: mental illness; grief caused by loss (“not only by death, but also from social and relational loss,” said one social worker); family history of substance abuse or suicide; hopelessness; a previous attempted suicide; and the lack of a strong support system.

“We need to apply the airport mantra of ‘see something, say something’ to all of society,” says Shaler, author of the recently released book Reclaiming Sanity. “If you have any reason to believe someone you know is suicidal, reach out to them. Some things to look for include a change in personality, giving belongings away, isolation, depression, and talk of suicide.”

Licensed counselors propose certain measures to deal with the threat guns pose to people at risk of suicide ideation. “Any additional amount of time to think before acting may result in a reduction in suicidal deaths,” says Shaler. “Handing out gun locks to anyone who may potentially become suicidal is one option.”

Other counselors believe emergency risk protective orders, in which a judge can order that firearms not be in close proximity to those who pose a threat to themselves, can be an effective tool. “At times, these are necessary steps to prevent a suicide until an appropriate safety plan can be enacted by a mental health professional, relevant authorities, and the respondent’s family and community,” says Branden Polk, a longtime social worker in the D.C. area.

He and Jefferson also recommend greater scrutiny be given to gun owners’ psychiatric health. “Mental health information related to homicidality and suicidality should be weighed when background checks are run for potential gun purchases,” Polk says.

Schenck focuses more on inspiring responsible choices than particular policies. “To me, the gun question is, at its core, a moral and ethical question,” he says. When pressed, he says lawmakers should limit who can carry a weapon with the purpose of killing. Yet he emphasizes personal responsibility over government measures, including in online articles he’s written. “The NRA is missing the moral and ethical dimensions of this issue,” Schenck says. “Maybe the subject at the next annual NRA convention should be: ‘When is it moral to own a firearm, and when is it immoral to own one?’”

He adds, “For the Christian, the decision is first moral and ethical. Only after that is it of any legal interest at all.”

ON THE HEELS OF The Armor of Light’s success, in January Schenck launched The Dietrich Bonhoeffer Institute (TDBI), a platform to examine moral and ethical issues using the German theologian’s biblical insights as a guide. Pastors count Bonhoeffer’s The Cost of Discipleship and Life Together as essential reading. His works are all the more compelling in light of how he joined a plot to assassinate Adolf Hitler, only to be executed be the Nazi regime.

Before his death at age 39, Bonhoeffer wrote more than 10,000 pages—a treasure trove for Schenck. It’s in these writings that Schenck reconciles what seems to be an oxymoron: How can he look to a spy for ethical guidance on issues like firearms? “Bonhoeffer was watching his country, his fellow Germans, face annihilation,” Schenck says. “It was very clear that Bonhoeffer believed that kind of action could be taken only in extremis, in the worst possible circumstances. ‘This is a unique time, place, and circumstances calling for unique action,’ he would say.”

With a staff of five, including two shared with Faith And Action, the new Institute has ambitious goals. Schenck and his team will sift through the 100,000 faith leaders, churches, and other ministries in their existing network to hone in on those bold enough to engage the questions TDBI has started to raise. Bonhoeffer spoke into the spiritual, moral, and ethical crises of his day, including how the church idolized political leaders such as Hitler, notes Schenck. Thus, TDBI will broadly address “the problem of idolatry,” he says. “It comes in many different forms—from religious legalism and zealotry, to political ideologies, and everything in between.”

They’ve started by targeting a golden calf that few dare to speak of in church: the intertwined issues of guns and suicide. These efforts will not bring back the lives lost already. But perhaps their unwavering focus on “the image of God in every human being” may yet open eyes and cause believers to cling more loosely to things that harm.

Josh M. Shepherd covers culture, faith, and public policy issues for media outlets including The Federalist and The Stream. A graduate of the University of Colorado, he previously worked on staff at The Heritage Foundation and Focus on the Family. Josh and his wife live in the Washington, D.C., area.

If you are thinking of hurting yourself, or if you are concerned that someone else may be suicidal, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255).