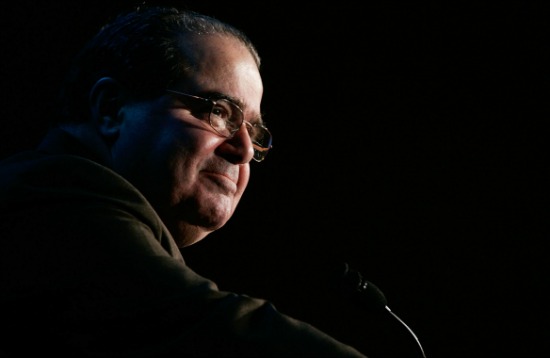

(Getty/Alex Wong)

As efforts are made to assess the legacy of Justice Antonin Scalia, who died last month, pundits have avoided discussing the one decision that stands as the biggest enigma in his corpus of largely conservative judicial decisions: Employment Division v. Smith, the historic case that repudiated the existence of a free exercise right to religious accommodation. Today, religious accommodation is championed by religious conservatives, who usually counted Justice Scalia as a friend, but remain mystified by what they perceive as his betrayal in Smith. The backlash against Smith, which outraged both liberals and religious conservatives at the time it was handed down in 1990, led to the unlikely political coalition between civil libertarian organizations and conservative religious advocacy groups that brought us the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (“RFRA”), the statute that supplied the basis of the controversial Hobby Lobby decision. That 2104 decision, which Justice Scalia joined, recognized the right to religious accommodation claimed by a family-owned business that objected to including coverage for contraception in its employee health insurance plan as required by the Affordable Care Act.

Scalia’s shift on religious accommodation in Smith confounded religious conservatives. It also has confounded liberals, who themselves have shifted their stance on religious accommodation, today embracing the arguments against religious exemptions from general laws of neutral application espoused in Scalia’s Smith opinion. Many of the tributes to Antonin Scalia written since his death have drawn attention to the times when he sided with the liberal justices on the Supreme Court, focusing in particular on the opinions in which he supported procedural rights for criminal defendants and the right to free speech. Yet none of these encomia to Justice Scalia’s “liberal side” discuss his Smith decision, even though it might be regarded as his most liberal decision of all. The omission of Smith from the accounts of Scalia’s “liberal” decisions reflects the politically ambiguous nature of the Smith opinion. That in turn reflects ambiguities within both liberalism and conservatism writ large.

Justice Scalia’s assertion in Smith that “the right of free exercise does not relieve an individual of the obligation to comply with a ‘valid and neutral law of general applicability’” was widely viewed by religious conservatives as contradicting their longstanding mission to protect rights to conscientious objection and religious accommodation. Yet it was the liberal Warren Court that first held that the Free Exercise Clause mandates religious exemptions from regulations that impose a substantial burden on religion unless the government can demonstrate a compelling interest in enforcing the regulation. Written by Justice Brennan, the most notoriously liberal member of the Supreme Court, that decision, known as Sherbert v. Verner, was based on quintessentially civil libertarian logic. It represented a mid-century consensus among religious rights advocates and secular liberals that freedom of religion was, like freedom of speech, a civil liberty that warranted strong protection from the Supreme Court.

That consensus proved to be fleeting. But the way it broke down defied any simple black and white distinction between the politics of the right and the left. Indeed, even before Sherbert was decided, the seeds of that breakdown could be seen. In 1961, just two years before it issued its decision in Sherbert, the Supreme Court handed down two decisions involving the conflict between Saturday Sabbath observance and laws reflecting the norms of the Christian majority. One, known as Braunfeld v. Brown, rejected a free exercise claim to a right to a religious exemption from Sunday Closing Laws made by Orthodox Jews who owned retail businesses, who argued that they deserved relief from the competitive disadvantage of having to close two days a week instead of just one. Contrary to the Sherbert decision, which viewed conditioning the receipt of economic benefits on sacrificing one’s religious belief as a substantial burden, Braunfeld held that merely making the practice of religion more expensive is not an infringement on the rights protected by the Free Exercise Clause. This decision was in keeping with the Court’s judgment in McGowan v. Maryland that same year, which held that Sunday Closing Laws do not violate the Establishment Clause or the Fourteenth Amendment’s guarantee of equal treatment.

Sherbert v. Verner also involved a conflict between a Saturday Sabbath observer and the Christian calendar, although in that case the Saturday Sabbath observer was a Seventh-day Adventist. Her claim to unemployment benefits was denied because she lost her job due to her refusal to work on Saturdays, a denial of benefits that the Supreme Court found to be unconstitutional. Sherbert thus represented a sharp divergence from the approach to analyzing the conflict between Saturday Sabbath observance and majority practices taken in McGowan and Brauner. Whereas McGowan denied that Sunday Closing Laws discriminated in favor of Christians (a position the Court sustained by denying that the Sunday Closing Laws were religious in nature at all), Sherbert took note of the fact that the state in question (South Carolina) “expressly save[d] the Sunday worshipper from having to make the kind of choice which we here hold infringes the Sabbatarian’s religious liberty,” characterizing the preferential treatment of Sunday over Saturday Sabbath observance as a form of religious discrimination.

Three decades later, in Smith, Scalia would repudiate Sherbert, thereby vindicating his youthful view of the legitimacy of laws that favor the religious practices of the Christian majority, while at the same time disappointing his conservative Christian supporters who strongly supported Sherbert’s principle of a right to religious accommodation. Twenty-four years after that, in 2014, Scalia would confound people again by recognizing a right to religious accommodation in the Hobby Lobby case that seemed to many observers at odds with the position he had taken in Smith.

Indeed, by the time that Hobby Lobby rolled around, the views Scalia had espoused in Smith had become the favored positions of progressives. Scalia had cautioned in Smith that “[t]o make an individual’s obligation to obey such a law contingent upon the law’s coincidence with his religious beliefs, except where the State’s interest is ‘compelling’ … permit[s] him, by virtue of his beliefs, ‘to become a law unto himself.’” This is exactly the concern now being voiced by progressives. They use this argument to counter conservative religious claims to a right to exemption from laws that offend their beliefs, like anti-discrimination laws that require providing goods and services to homosexual individuals and laws requiring health plans to cover contraception.

So whose position here is the liberal one? And whose is conservative? And how does the position that Justice Scalia took in the Smith case cohere with the position he took in the Hobby Lobby case, where he sided with the majority opinion, which granted business owners the right to an exemption from the Affordable Care Act’s contraceptive mandate on the basis of their religious objections?

The key to understanding Scalia’s views about the place of religion in the constitutional order can be found in his thoughts about the early Sunday Closing Law cases. As recollected by Nathan Lewin, in a fascinating reminiscence published a few weeks ago under the title of “The Supreme Court’s Jewish gentile: My memories of Justice Scalia,” he and Scalia were both Harvard Law students serving as editors on the Harvard Law Review in 1960 when the Sunday Closing Laws cases were being argued. While they were and remained good friends, Lewin recalls that he and Scalia battled “over whether a student-authored note should support the constitutional rights of Sabbath-observant business owners,” with Scalia championing the position that ultimately prevailed in McGowan and Brauner, denying the right of Saturday Sabbath observers to religious accommodation or to overturn the Sunday Closing laws.

Scalia’s views about a judicially enforceable right to religious accommodation may have shifted over the years, but, as his opinion about the Sunday Closing Law cases indicates, his belief in America as a Christian nation was unwavering. While the Warren Court defended the constitutionality of Sunday Closing Laws on the dubious grounds that they were no longer Christian in character, Scalia’s Establishment Clause decisions once he was on the bench would make clear that he had nothing but contempt for such ruses. He rejected the idea that observances of holidays and displays of religious symbols by the government had to be described as having undergone a process of secularization in order to withstand constitutional scrutiny. In the two Ten Commandment display cases heard in 2005, he flatly rejected “the Court’s oft repeated assertion that the government cannot favor religious practice,” or “religion over irreligion,” calling it “demonstrably false.” In other words, he maintained that the government can favor religious practice and engage in “public acknowledgment of religious belief.” He went on to claim that “the Court’s assertion that governmental affirmation of the society’s belief in God is unconstitutional” was based on nothing “except the Courts own say-so,” clearly suggesting that the affirmation of belief in God, through state-sponsored displays of religious symbols and other forms of government religious expression, is constitutional.

Similarly, in Lee v. Weisman, a school-prayer decision issued in 1992, just two years after Smith in 1992, Justice Scalia wrote in dissent that the Establishment Clause prohibition on government endorsement of religion only applies to the endorsement of sectarian beliefs “upon which men and women who believe in a benevolent, omnipotent Creator and Ruler of the world are known to differ (for example, the divinity of Christ).” In other words, the government and public entities like public schools cannot take sides in the debates that divide Catholics from Protestants, or different schools of Protestantism from one another. But, according to Justice Scalia, they most certainly can endorse and sponsor religious exercises that express the belief in a “benevolent, omnipotent Creator and Ruler of the world” ostensibly shared by all Christians. In this particular case, the prayers that Justice Scalia would have upheld were offered by a rabbi, indicating his view that such “nonsectarian” religion embraces Jews as well. He likewise asserted that the ecumenical belief in a “single Creator” expressed by the Ten Commandment displays embraced all three of the “most popular religions in the United States, Christianity, Judaism, and Islam”—this notwithstanding the fact that Judaism and Christianity have different versions of the Ten Commandments and the monuments in question not surprisingly adopted the version favored by their Christian sponsors, while any version of the Ten Commandments occupies a far less prominent symbolic place in Islam than it does in either Judaism or Christianity. But Scalia refused to let such distinctions get in the way of his preferred version of religious ecumenicism. More recently, in The Town of Greece v. Galloway, he went beyond this strained version of ecumenicism, joining Justice Alito’s opinion, which upheld the practice of delivering Christian prayers before town meetings against an Establishment Clause challenge. Together, Alito and Scalia dismissed the dissenters’ concern that the practice would make non-Christians and non-believers feel like outsiders and unequal citizens as a fanciful hypothetical.

While Justice Scalia’s opinion in Smith might appear to be an outlier in this otherwise unbroken string of opinions supporting positions taken by religious conservatives, it actually can be seen as quite consistent with his case for government religious endorsement—and with his youthful enthusiasm for the cases that upheld the constitutionality of Sunday Closing Laws. For both the denial of the right to religious accommodation in Smith and Scalia’s belief in the government’s authority to sponsor religious exercises like school and legislative prayer proceeded from his oft-stated commitment to a majoritarian conception of our constitutional democracy. He was unabashed about the consequences of this position for religious minorities as opposed to the majority. He was particularly explicit about this in Smith, which included this notable passage, reminiscent of his indifference to the feelings of religious minorities and nonbelievers expressed in Town of Greece:

It may fairly be said that leaving accommodation to the political process will place at a relative disadvantage those religious practices that are not widely engaged in; but that unavoidable consequence of democratic government must be preferred to a system in which each conscience is a law unto itself or in which judges weigh the social importance of all laws against the centrality of all religious beliefs.

Justice Scalia’s willingness to deny religious minorities exemptions from laws that conflict with their beliefs was of a piece with his belief that the government’s espousal of generic Christian beliefs did not flout the Establishment Clause. Both were born of his confidence in the existence of a Christian majority whose beliefs would naturally be reflected in the laws enacted through a democratic process. It was only when his confidence in the continued existence of a Christian political majority began to be challenged—as it was most clearly when what he vilified as the “homosexual agenda” triumphed politically in the legislature and in the courts—that he began to change his tune about the rights of religious minorities to religious accommodation. Then, suddenly, he got the religion of accommodation, which Christians now said they had a right to as the new minority.

But if Scalia flip-flopped on the issue of the right of minorities to religious accommodation, so too progressives have reversed their position on majoritarianism, endorsing the view that Justice Scalia put forth in Smith that religious believers cannot be permitted to make their religion a law unto themselves. This is a liberal position insofar as it justifies the enforcement of progressive laws, like the Affordable Care Act and anti-discrimination laws, against conservative conscientious objections. But it is also a quintessentially conservative position inasmuch as it upholds the need for law and order against individual liberties and the anarchical freedom to do whatever one wants or personally believes is right. This is traditional political conservatism of a Hobbesian kind, and if it is at odds with the conservatism of the religious right, that suggests that there are fissures within American conservatism (and American liberalism) that need to be brought to light. Justice Scalia’s jurisprudence of religion reflected these fissures. At the same time it revealed his staunch commitment to maintaining the Christian character of America.

Nomi Stolzenberg is the Nathan and Lilly Shapell Chair in Law at the University of Southern California Law School. She is the director of USC’s Program on Religious Accommodation and co-directs USC’s Center for Law, History and Culture.