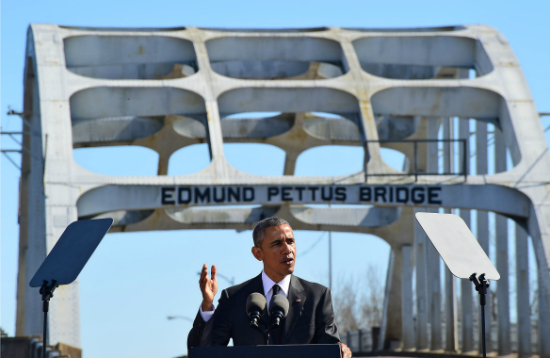

Speaking at the ceremony marking the 50th anniversary of the Selma to Montgomery marches last month, President Obama posed a question that captured why many continue to view him as hope personified, while others seem to see him as an existential threat. “What greater form of patriotism is there than the belief that America is not yet finished?” he asked.

“Not yet finished”: That’s the line that separates worship of the founders from belief in the unrealized potential of what they began; it divides those who are nostalgic for freedoms supposedly lost which now must be restored, from those who recognize that the freedoms enjoyed by some have always been partial, while the struggle continues to guarantee them for all.

In case anyone missed that first “not yet,” Obama offered it four more times before the Selma speech was done: “We know the march is not yet over. We know the race is not yet won … Fifty years from Bloody Sunday, our march is not yet finished, but we’re getting closer. Two hundred and thirty-nine years after this nation’s founding our union is not yet perfect, but we are getting closer.”

More than merely a well-crafted string of phrases on a significant occasion, the notion that the United States is “not yet perfect” may be the single most enduring theme of Obama’s political life.

The speech largely credited with saving his candidacy in 2008—itself called “A More Perfect Union”—relied on the rhetorical interplay of “perfect” as an adjective and “perfect” as a verb. “This union may never be perfect,” he said, “but generation after generation has shown that it can always be perfected.”

Given in response to the controversy surrounding his longtime pastor Jeremiah Wright, the speech addressed race especially as “a part of our union that we have yet to perfect.”

This was for him not only an assessment of history, but a profession of faith. “I have asserted a firm conviction—a conviction rooted in my faith in God and my faith in the American people,” he said, “that working together we can move beyond some of our old racial wounds, and that in fact we have no choice if we are to continue on the path of a more perfect union.”

Many commentators have proposed that the president’s “A More Perfect Union” speech and his recent remarks in Selma are companion pieces. But they might be seen instead as reframings of the same simple yet subtly subversive idea that has repeatedly emerged for Obama at moments of crisis or reflection: While at no point in its history could the United States be described as perfect, he insists, it remains the responsibility of its citizens to attempt to perfect it. Hints that the word matters more to him as an act than a description were there even in his 2007 announcement that he would seek the presidency: “I want us to take up the unfinished business of perfecting our union, and building a better America.”

Given the number of times he has said the words, and all that those words say about his understanding of what the country has been and could be, there’s a case to be made that “Not Yet Perfect” might prove to be Obama’s “Shining City Upon a Hill.”

Of course, it is also the antithesis of everything Ronald Reagan intended whenever he used that more famous phrase. For Reagan, the biblical “city upon a hill,” which Governor John Winthrop entreated the settlers of Massachusetts to build, presented a scriptural vision of history as something to be emulated rather than overcome. And while the promise of “not yet perfect” is for Obama ultimately a matter of faith, Reagan’s “city” suggests a very different religious interpretation of the past. As he explained a moment before he first used the phrase, at Conservative Political Action Conference in 1974:

You can call it mysticism if you want to, but I have always believed that there was some divine plan that placed this great continent between two oceans to be sought out by those who were possessed of an abiding love of freedom and a special kind of courage … Call it chauvinistic, but our heritage does set us apart.

Reagan would go on to use his version of the “city upon a hill” at every major juncture in his public life, including three campaigns for the presidency, two administrations, and most significantly in the farewell address that marked his departure from the national stage. Describing his last week in the White House in January 1989, he closed his final remarks as president with an elaboration of his understanding of what Winthrop might have had in mind three and a half centuries before:

The past few days when I’ve been at that window upstairs, I’ve thought a bit of the “shining city upon a hill.” The phrase comes from John Winthrop, who wrote it to describe the America he imagined. What he imagined was important because he was an early Pilgrim, an early freedom man. He journeyed here on what today we’d call a little wooden boat; and like the other Pilgrims, he was looking for a home that would be free.

I’ve spoken of the shining city all my political life, but I don’t know if I ever quite communicated what I saw when I said it. But in my mind it was a tall, proud city built on rocks stronger than oceans, wind-swept, God-blessed, and teeming with people of all kinds living in harmony and peace; a city with free ports that hummed with commerce and creativity. And if there had to be city walls, the walls had doors and the doors were open to anyone with the will and the heart to get here. That’s how I saw it, and see it still.

Had PolitiFact been around in 1989, someone might have noted that Winthrop’s city was never “shining,” nor was it as well established as the thriving and cinematic cityscape Reagan described. It is also a remarkable feat of revisionism to praise the governor who exiled iconic figures of early American religious dissent like Anne Hutchinson and Roger Williams as a “freedom man.”

Yet the most interesting departure from history in this American creation myth may be that though Reagan spoke often of the courage it took to reach this city, his city upon a hill, “built on rocks stronger than oceans,” was divinely guaranteed success in a way Winthrop’s was not. The past was not only prologue, it was an ideal to which he hoped the nation might return.

In the forty years since Reagan successfully repainted the origins of the United States with this broad brush, nearly every national candidate has repeated some version of “city upon a hill” as creed and shibboleth. Even Obama made use of this well-worn phrase—and perhaps inevitably he did so through the filter of “not yet perfect.” Invoking Winthrop while speaking in Massachusetts as the junior senator from Illinois, he delivered a 2006 commencement address that at once echoed and questioned earlier allusions:

It was right here, in the waters around us, where the American experiment began. As the earliest settlers arrived on the shores of Boston and Salem and Plymouth, they dreamed of building a city upon a hill. And the world watched, waiting to see if this improbable idea called America would succeed.

For over two hundred years, it has. Not because our dream has progressed perfectly. It hasn’t. It has been scarred by our treatment of native peoples, betrayed by slavery, clouded by the subjugation of women, wounded by racism, shaken by war and depression. Yet, the true test of our union is not whether it’s perfect, but whether we work to perfect it.

Obama’s “city upon a hill” did not depart as far from Reagan’s interpretation as it at first might seem. After all, he still insisted that it was with a Puritan dream that the “American experiment began.” He would not embrace this dream, however, without acknowledging how it had been “scarred”—a mixed metaphor, but an arresting one: a wounded city upon a wounded hill.

Taking into account as it does the many ways the country it describes has not lived up to its ideals, this revised sense of the “city upon a hill,” has not yet supplanted the 40th president’s “shining” notion, and it is unlikely to do so. But in any case, since Obama first spoke the words nearly a decade ago, the limits and the potential of the nation’s perfectability have set the tone for much of the campaign and presidential rhetoric that followed.

Heard by some as an apology or admonishment, and by others as a stirring call to action, recognition of the nation’s flaws is risky political theater. Yet after overwhelming victories in two elections, Obama’s past imperfect has mostly paid off— certainly in terms of his own astonishing rise, and perhaps also as a catalyst for increased willingness to consider the light and the dark of the nation’s history.

Only the coming campaign season will tell if this kind of retrospection has had lasting effect. When asked to choose between directions for the future, voters in 2016 may also face a choice between visions of the past.

Peter Manseau is the author most recently of One Nation Under Gods: A New American History, from which this essay is adapted. Follow him on Twitter @petermanseau.