My childhood was oriented around Nebraska Cornhusker football. A pastor’s kid growing up in McCook, a town of 8,000 in southwest Nebraska, I came of age during the Cornhuskers’ string of championship runs in the 1990s. I was more likely to skip church on Sunday than miss the Saturday radio or television broadcast of the Cornhusker game. Occasionally I scored tickets to see the action in person. I have vivid memories of the four-hour pilgrimage east to Memorial Stadium in Lincoln, where I joined fellow Huskers as we sang hymns like “Dear Old Nebraska U,” chanted “Husker Power!” and participated in the call-and-response liturgy of “throwing the bones” (crossing our arms into an X) after a spectacular defensive play.

Not everyone in Nebraska roots for Cornhusker football, but nothing else unites the state quite as much. Even for dissenters, the power of the Big Red cannot be avoided. Fall weddings must be planned around football games; trips out in public on game day must be taken with the assumption that the radio broadcast will be piped through the speakers of whatever establishment you are visiting. It is no wonder that scholars have found Cornhusker fans useful when exploring the “sports-as-religion” thesis.

There are plenty of others states that love college football (see: every state in the South). But there is something different about the context in which Nebraska football operates. This difference can be traced, in part, back to the Morrill Act of 1862. The law offered the sale of federal lands in the West (lands from which American Indians were forcibly removed) to fund the establishment of land-grant colleges in participating states. In states like Kansas (Kansas State), Alabama (Auburn), and South Carolina (Clemson), the Morrill Act funded new public colleges separate from the state university—inadvertently creating long-lasting intrastate athletic rivalries. Elsewhere, in states like Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Nebraska, the state university and land-grant college were joined together in one institution. The decision by Nebraska to create one unified statewide public institution of higher education—combined with the absence of professional teams or large private universities—ensured that as college athletics developed in the twentieth century, the loyalties of Nebraska’s football fans would be united. “No mountains. No beaches. No big-league teams,” Tom Callahan wrote in TIME in 1983. “Other than slow-changing seasons, burning summers, bitter winters, and autumns that can be rather a brilliant compensation, only this football team gathers up an entire state of people and brings them to one emotional place.”

The University of Nebraska first fielded a football team in 1890. By 1893 Nebraska student Willa Cather was singing the praises of the program. “A good foot ball game is an epic,” Cather wrote in the student newspaper, “it rouses the oldest part of us.” From 1900 until 1940, the Cornhuskers had only two losing seasons, emerging as a national football power. The team struggled in the 1940s and 1950s, but as more Nebraskans attended the school in the postwar years and as the era of big-time college athletics emerged, head coach Bob Devaney led a Big Red renaissance. Under his watch, which stretched from 1962 until 1973, Nebraska won 81 percent of its games, eight Big Eight conference titles, and two national championships. Devaney’s successor, Tom Osborne, kept the football program rolling until his retirement in 1998. Osborne’s last five years were especially remarkable: from 1993 until 1997, the Cornhuskers won as many national championships (three) as they lost games.

Devaney and Osborne are both revered figures in the state. It’s fitting that they also represent Nebraska’s two leading twentieth-century religious denominations: Roman Catholicism (Devaney) and United Methodism (Osborne).

Devaney generally didn’t make a public display of his Catholicism, but some Catholics in Nebraska found it necessary to make a public display of their Cornhuskerness. This was particularly true in 1973, when Nebraska and Notre Dame matched up in the Orange Bowl. Loyalties collided: while the Cornhuskers claimed to represent Nebraskans, Notre Dame claimed the same for America’s Catholics. In Huskerville: A Story of Nebraska Football, Fans, and the Power of Place, Roger Aden recounted the story of a young Nebraska Catholic boy going to mass on the day of the game. “The entire parish was wearing red,” the fan recalled. “They wanted to show that the fact they were Catholic did not mean they were going to refuse to be Nebraskans.”

Under Devaney, Cornhusker football became a kind of religion of its own. Under Osborne, the state’s devotion to the program became a means through which Christianity could be promoted. One of the primary beneficiaries and agents of this mingling of faith and football was the Fellowship of Christian Athletes (FCA).

FCA, founded in 1954, was viewed early on as a tool to harness the nation’s growing obsession with sports and use it for civic good by channeling it into Christian expression. FCA aimed to strengthen Christian churches with an infusion of newly committed Christian youth, who would then go on to make better citizens. Few raised eyebrows as FCA’s celebrity athletes came to public schools in the South, Midwest, and California, dishing tales from the big leagues and selling students on the benefits of Christianity. True to its ecumenical nature, an FCA campaign in Omaha in 1957 featured stops at public schools and Catholic schools. But despite its more broad-based appeal in the 1950s, by the 1970s FCA had moved decisively into the conservative evangelical sphere alongside organizations like Campus Crusade for Christ.

Osborne’s connection to FCA dates back to 1957 when he had a profound religious experience while attending a national FCA camp. As he wrote in his book More Than Winning, “Until 1957, most of what I believed about God was a sort of second-hand religion.” At the FCA camp that year he mingled with Christian sports stars. For the first time, he recalled, Christianity seemed exciting. By the end of the camp Osborne felt that “my faith really became my own.”

In 1967, soon after Osborne became an assistant at Nebraska, he helped launch an FCA huddle on campus. As FCA expanded in the state and as its institutional infrastructure matured, Osborne provided FCA with access to the Nebraska football team and served as a powerful statesman for the organization. FCA huddle groups in Nebraska expanded from 30 in 1976 to 220 by 2001. In the 1980s, a “Cornhuskers for Christ” group featuring Nebraska football players regularly toured the state; by the mid-1990s Cross Training, a publishing house based in Nebraska, churned out books connecting Cornhusker football with the conservative evangelical faith favored by FCA. I still have from my childhood library four Cross Training books: I Can, a religious biography of Nebraska assistant football coach Ron Brown; Lessons from Nebraska Football, featuring moments from Nebraska football history combined with bible lessons; Hearts of Champions, a collection of twenty evangelical conversion narratives from Cornhusker coaches and players; and One Final Pass, a biography of Nebraska quarterback Brook Berringer, who tragically died in 1996 while flying to speak at an FCA event.

Berringer’s story, in particular, shows just how connected FCA was with Nebraska football. In 1995 during his senior season, Berringer became born-again through relationships developed in FCA. Months later, in April 1996, the beloved backup quarterback died in a plane crash, triggering a statewide outpouring of emotion. Ron Brown immediately saw the evangelization potential: in print, radio, and television media across the state, he (and other FCA leaders) highlighted Berringer’s recent conversion and the suddenness of his death. Would Nebraskans catch Brook’s “one final pass,” Brown asked in a video made with support from the University of Nebraska athletic program, and accept Jesus Christ as their personal Lord and Savior?

For many Nebraskans, using Nebraska football to evangelize was not a problem. Since the 1940s Nebraska had been a bastion of conservative politics and Nebraskans generally supported a prominent public role for Christian institutions and expressions. Most Nebraskans took it for granted that faith was a central part of the Cornhusker program. It helped that many Nebraskans saw in FCA a generalized Christianity imbued with the character traits and values Nebraskans liked to think that they possessed in a unique way: working hard, doing things with integrity, believing in a higher power; “Not the victory but the action; Not the goal but the game; In the deed the glory,” goes the oft-quoted phrase inscribed on the southwest corner of Memorial Stadium. Those generalized notions of Christianity were what Sister Mary Hlas, a nun well-known for her Husker enthusiasm, had in mind in 1982 when she congratulated “Tom Osborne and his players” because they “are not members of the Fellowship of Christian Athletes in name only, but they truly live out their philosophy.”

For his part, Osborne cultivated goodwill by leaning towards an irenic, cooperative brand of evangelicalism. He remained a member of the United Methodist church and he encouraged players to pursue the benefits of a committed spiritual life within their chosen religious traditions. Thus, when Milt Cooper, the national director of programs for FCA, said in 1998 that “the Christian atmosphere” within the Nebraska football program was “one of the best in the nation, if not the best,” most Cornhusker fans took it in stride, if not pride.

But not all Cornhusker fans. The team was too central to the state’s identity to allow its connection with an evangelical-leaning Christianity—or even a generalized Christianity—go unchallenged. Especially for those affiliated with the Nebraska ACLU, the public Christian image was potentially unconstitutional. Beginning in the 1990s, the ACLU increasingly scrutinized FCA’s access to Cornhusker football and to public high schools. In response, FCA defended itself on legal grounds and argued that the ACLU’s views represented only a tiny fraction of Nebraskans. Since the majority of Nebraskans did not oppose what FCA was doing, why did the ACLU have a problem?

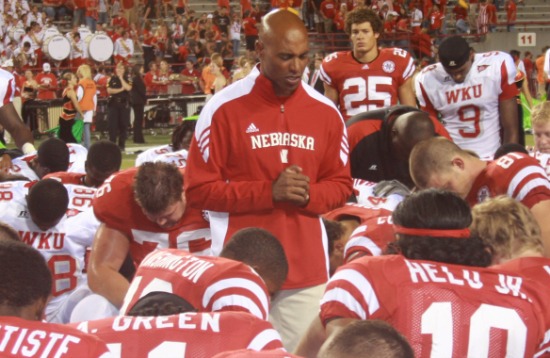

The frequent battles between the ACLU and the FCA often centered on the actions of Assistant Coach Ron Brown, the leading representative of the FCA/Cornhusker fusion in the post-Osborne era and a longtime member of an evangelical, nondenominational church in Lincoln. As an African American, Brown occupied a unique place of prominence in Nebraska. African Americans constitute just five percent of the state’s population, but are usually a majority of the football team’s starting lineup. Brown used his position to support racial equality and reconciliation—albeit in ways that other African American leaders, like longtime State Senator Ernie Chambers, found ineffective.

Unlike Osborne, Brown wears his evangelistic zeal on his sleeve, and he has often spoken out against homosexuality. For example, in 1999 on his weekly radio show he called on Christians not to abandon gay and lesbian individuals to “a politically correct world that honors this lifestyle.” Rather, Brown said, Christians should “win the homosexual to Christ” through love and active evangelism. Brown’s supporters have claimed that he treats all his players with equal respect, even if they disagree with his religious views: Eric Lueshen, an openly gay player, and Ameer Abdullah, a Muslim player, seem to back this up in supportive statements they have made about Brown. Yet for Brown’s opponents, his treatment of individual players did not take away from the controversy of his public statements. Nor did it address the larger structural and power issues at play. The matter for them was simple: Brown used his position in a public university to tirelessly promote his exclusionary conservative evangelical views and to demonize those in the LGBT community. “Nebraska is not a Christian state,” Rabbi Aryeh Azriel of Omaha’s Temple Israel said in response to Brown in 1999. “The University of Nebraska is not a Christian university.”

For the most part the culturally conservative politics of Nebraska meant that Brown was protected from his opponents. But the tide began to shift somewhat in 2012, when he gained national attention for publicly opposing an ordinance in Omaha that would ban discrimination on the basis of gender identity and sexual orientation. Before making his public comments, Brown listed his address as “Memorial Stadium.” His appropriation of a powerful state symbol prior to giving his inflammatory remarks raised the ire of his Nebraska opponents and more than a few national writers. Although Brown was not fired, and although he did not back down from his comments, even some of his supporters felt he had gone too far. Omaha World-Herald columnist Dirk Chatelain, who lauded Brown as a strong spiritual influence, nevertheless wrote that Brown spoke about homosexuality “in a way that reflects negatively on Nebraska and—more importantly—on Christianity.”

Brown’s forays into the political realm contrasted sharply with Osborne’s more moderate tone. Yet, even Osborne found that his football-based reputation could only carry him so far when it came to politics. After leaving coaching, Osborne served three terms in Congress for Nebraska’s third district, never receiving less than 82 percent of the vote. But then he lost his bid for governor in 2006 when he was defeated in the Republican primaries. The former coach faced an incumbent governor, and GOP voters disliked some of his moderate stances, such as his willingness to give college tuition rates to the children of undocumented immigrants. Though he never attained another elected office, his approval ratings did bounce back: A 2011 survey of the state by Public Policy Polling found Osborne to be “the most popular person PPP has ever polled on anywhere.”

Earlier this year Ron Brown announced his departure from Nebraska, a casualty of the recent firing of head coach Bo Pelini. His longtime co-laborer and former Husker Gordon Thiessen penned a heartfelt goodbye to Brown on an FCA website, commending him for using his “platform as a Husker football coach in a football-crazed state to tell people about Jesus.” Others probably felt less charitable. Regardless of one’s sentiments, it certainly felt like an era had ended: the link to the Osborne-initiated blending of faith and football was gone. Who will carry on the torch? Perhaps Brown’s departure portends to a future in which FCA does not have the same access to Nebraska football. Or perhaps another sport will take the lead. Nebraska’s wildly popular women’s volleyball team is coached by John Cook, another FCA stalwart whose connections may continue to pay dividends for the organization.

As those changes are sorted out, a new generation of Nebraskans—pastors’ kids and otherwise—are learning the rites and rituals of Cornhusker fandom. The glory years of the 1990s may seem like the distant past, but devotion to Cornhusker football remains strong. And as long as Cornhusker football serves as a powerful symbol of state identity, residents and organizations will continue to integrate faith and football—and to challenge unwanted attempts at such integration—in ways that inevitably spill over into politics.

Paul Putz is a PhD student in history at Baylor University. He lived in Nebraska for 28 years prior to moving to Baylor. Follow him @p_emory.