Wilhelm Keitel had been general field marshal, second only to Adolf Hitler in Germany’s military hierarchy. Now, on a cold, rainy October morning, at 1:00 a.m. in 1946, he stood shackled to a guard outside cell 8 of Nuremberg’s Palace of Justice. In half an hour, Keitel would be hanging by his neck from a rope, his hands tied behind his back with a leather bootlace, a black hood over his head. Outside the prison, no moon marked the sky above the destroyed city of Nuremberg.

The prison’s commandant, U.S. Army colonel Burton Andrus, spoke loudly, with both custom and history in mind. His voice was high pitched but authoritative, and it echoed off the prison’s dull stone walls and traveled up the metal staircases, past the mesh wiring that had been strung across the three tiers of cells to prevent suicides.

It traveled past a small chapel that had been created by knocking down the wall between two cells.

Andrus felt the weight of the moment, but he didn’t relish it. He walked along the cell block on the first level, stopping at each prisoner’s cell and repeating his sentence. The men had heard the same words two weeks earlier when the justices of the International Military Tribunal read the verdicts and sentences aloud in court.

The colonel was simply going through with a formality—required by the army’s standard operating procedure and the Geneva Convention. The men in these cells were the former elite of the Third Reich, but they had long since been stripped of any military rank or privilege. In Nuremberg’s prison, they were treated by most as persons without status.

Andrus was anxious and annoyed as he eyed Keitel. This was the date the tribunal had set for the executions, and while the prisoners didn’t know it officially, most of them had guessed these were their final hours. Earlier in the night, Hermann Goering, Germany’s former reichsmarshal, Hitler’s designated successor and the former head of Germany’s air force, had killed himself by swallowing cyanide, cheating justice and outfoxing Andrus, who had vowed that his prison would be suicide-free. The commotion that followed Goering’s death had woken the other prisoners. At 12:45 a.m., they were told to dress and were given their last meal: sausage, potato salad, cold cuts, black bread, and tea.

Most didn’t touch the food. Keitel had made his bed and asked for a brush and duster to clean his cell.

Keitel’s life had been ruled by army regulations. Since his capture by the Allies eighteen months earlier he had played the part of a disciplined soldier. His bearing was erect, his silver hair and mustache always perfectly trimmed. Keitel’s defense attorney had played on the notion of following orders. He had only been doing a job he’d trained for his entire life. Keitel’s commanding officer was the führer, and questioning orders was never even a consideration.

The tribunal had seen it differently. “Superior orders, even to a soldier, cannot be considered in mitigation where crimes so shocking and extensive have been committed,” the justices had said about Keitel’s defense. They found him guilty on all four counts of the Nuremberg indictment. When the justices told Keitel he’d been sentenced to death, the general nodded curtly and left the courtroom.

Now Keitel was hearing his sentence for the second and final time. “Defendant Wilhelm Keitel,” Andrus announced, “on the counts of the indictment on which you have been convicted, the Tribunal has sentenced you to death by hanging.”

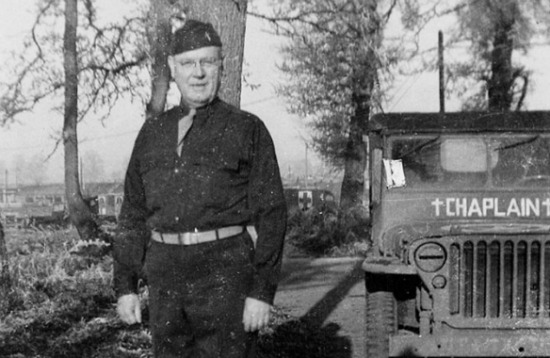

Once Andrus had moved to the next prisoner and Keitel had returned into his cell, a stocky man with glasses, receding gray hair, and a doughy face followed the field marshal to his cot. Chaplain Henry Gerecke, a captain in the U.S. Army, was carrying a Bible. He asked Keitel if he’d like to pray.

Gerecke (rhymes with “Cherokee”) had also been rattled by Goering’s suicide. An ocean away, Gerecke’s St. Louis Cardinals had been battling the Boston Red Sox in the World Series. The prison’s other chaplain, Father Sixtus O’Connor, was rooting for the Sox. They had been in the guards’ booth on the prison floor awaiting a telephone call when Goering bit down on the cyanide. With the Palace of Justice locked down for the executions, the only way the chaplains and guards had of receiving updates after each half inning was through phone calls from an American officer outside the prison walls. Just after a call came in that Boston’s Dom DiMaggio had doubled in the top of the eighth, driving in two runs to tie St. Louis, Goering’s guard began yelling that something was wrong; Gerecke was the first to get to the reichsmarshal as he died.

Two hours later, Gerecke was with Keitel. They sank to their knees in Keitel’s cell, and Gerecke began to pray in German. Andrus’s words must have triggered in Keitel the realization that his life was over, because his soldierly demeanor was suddenly shattered. His voice faltered. His prayer trailed off. He began to weep, then sobbed uncontrollably, his body jerking as he gasped for air. Gerecke raised his hand above Keitel’s head and gave the general a final benediction. Most likely it was Martin Luther’s favorite, from the book of Numbers: “The Lord bless you, and keep you; The Lord make his face shine on you, and be gracious to you; The Lord lift up his countenance on you, and give you peace.” Then the chaplain was called to the next cell, and he rose to his feet.

A LITTLE MORE THAN three years earlier, on June 3, 1943, Henry Gerecke was late for dinner. He burst through the front door and bounded up the wide wooden steps, two and three at a time, leading to the three-bedroom apartment at 3204 Halliday Avenue in south St. Louis that he shared with his wife, three sons, and sister-in-law. Gerecke’s wife, Alma, was the only one home. Her younger sister, Ginny, was out. The couple’s youngest son, fifteen-year-old Roy, was at a church youth group meeting. Gerecke’s two older sons had already joined the army. The eldest, twenty-two-year-old Hank, was in the Aleutian Islands, fighting off the Japanese threat to the North American mainland. Twenty-one-year-old Carlton—everyone called him Corky—was training at Fort Bliss, Texas, for the Normandy invasion that would take place the next year.

As Henry reached the top of the steps, panting, he knew he was about to tell a woman with two sons in the war that her husband was headed there, too. That, and he was late for dinner. He walked through the long hallway toward the back of the apartment, where the kitchen was, and sat down at the table. Alma’s back was to him. His dinner was already on the table. It was lukewarm, but Henry began shoveling the food down. Alma was silent.

“Do you know something?” he asked brightly. “I got the idea today I’d like to join the Chaplains Corps.” More silence. Henry kept eating. Still nothing from his wife. “I asked you something,” he said.

“I heard you,” Alma said, finally. “I’ve heard you right along.” She took her time. She dried another dish. “But I want to tell you something. If the army has come to such straits that men of your age have to go into the Chaplains’ Corps, I feel sorry for the army.”

Alma had a point. By the summer of 1943, the army was desperate for chaplains. It needed thousands more. The ratio of one army chaplain for every thousand soldiers was better than in the First World War, when the ratio was one chaplain for every twenty-four hundred men. But it wasn’t quite good enough. “As the tempo of the war increases, the soldiers’ interest in spiritual matters also increases,” General William R. Arnold, the army’s chief of chaplains, told a newspaper that summer. “Reports from our chaplains in the battle areas tell of the increased opportunities afforded them and because such conditions prevail, I believe you will agree that we dare not fail these men by not supplying them with enough chaplains.”

He urged church organizations to “rob their parishes of priests and ministers, if necessary, to supply spiritual advisors for our troops.” Arnold stressed that the army wanted chaplains under the age of forty-five for service with combat troops. “At present there are no vacancies for those over 50.”

Gerecke’s fiftieth birthday was two months away. Alma’s joke about the Chaplain Corps was her way of letting her husband know she’d accepted the situation. She knew he had already made up his mind.

Gerecke volunteered just before his birthday, and two months later he reported for duty at the Chaplains School at Harvard University. Five weeks after that, the army assigned him to the Ninety-Eighth General Hospital, a newly formed unit at Fort Jackson, South Carolina. In February 1944, the army directed the hospital unit to Camp Myles Standish in Massachusetts, and then on to England. Eighteen months later Gerecke was in Germany and was handed an assignment he was allowed to refuse. He could go home to St. Louis, to Halliday Avenue, to Alma. Instead, he took the assignment, and later he considered his time in Nuremberg the most important year of his life. Gerecke’s ministry at Nuremberg has been called “one of the most singular … ever undertaken by U.S. Army chaplains.” It was a historic experiment in how good confronts radical evil. And at its center was a farm kid from Missouri.

Gerecke, the Lutheran preacher from St. Louis who ministered to the agents of the Third Reich, was one player in a judicial improvisation we now call simply the Nuremberg trials. They were “trials”—plural—because the most famous proceeding, officially called the Trial of the Major War Criminals before the International Military Tribunal, was only the first in a series that took place in the German city of Nuremberg lasting until 1949. But that first trial overshadows the rest. When most people refer to “Nuremberg,” they mean the Trial of the Major War Criminals. For the first time in history, the international community held a state’s major leaders accused and convicted them of conspiring to commit crimes against humanity. Nuremberg was, in the words of one of its American prosecutors, “a bench mark in international law and the lodestar of thought and debate on the great moral and legal questions of war and peace.”

Hans Fritzsche, on trial as Hitler’s radio propaganda chief and a member of Gerecke’s Nuremberg flock, wrote later that when Gerecke first arrived at the prison in November 1945, just days before the trials began, the chaplain “made scarcely any impression on us. Some of us may even have smiled at his simple, unequivocal faith and unpretentious sermons.” It was the victorious Allies who were judging the crimes of the Nazi leaders at Nuremberg, but it would be a pastor of the Lutheran Church–Missouri Synod who would try and convince those criminals that it was really God’s judgment that they should fear.

For Gerecke, the decision to accept the assignment wasn’t easy. He wondered how a preacher from St. Louis could make any impression on the disciples of Adolf Hitler. Would his considerable faith in the core principles of Christianity sustain him as he ministered to monsters? During his months stationed in Munich after the war, Gerecke had taken several trips to Dachau. He’d seen the raw aftermath of the Holocaust. He’d touched the inside of the camp’s walls, and his hands had come away smeared with blood.

The U.S. Army was asking one of its chaplains to kneel down with the architects of the Holocaust and calm their spirits as they answered for their crimes in front of the world. With those images of Dachau fresh in his memory, Gerecke had to decide if he could share his faith, the thing he held most dear in life, with the men who had given the orders to construct such a place.

Fritzsche wrote later:

Pastor Gerecke’s view was that in his domain God alone was Judge, and the question of earthly guilt therefore had no significance so far as he was concerned. His only duty was the care of souls. In a personal prayer which he once made aloud in our queer little congregation he asked God to preserve him from all pride, and from any prejudice against those whose spiritual care had been committed to his charge. It was in this spirit of humility that he approached his task; a battle for the souls of men standing beneath the shadow of the gallows.

WHEN GERECKE RETURNED to Keitel’s cell about 30 minutes after his initial visit in those early morning hours, he was visibly shaken from just having escorted Joachim von Ribbentrop, Hitler’s foreign minister, to the gallows. It was the first time Gerecke had seen someone put to death. Now he was at Keitel’s cell, and the two again prayed through Keitel’s tears.

But then it was time to go, and they started down the corridor. Andrus was in front, his cavalry boots clacking on the prison’s cement floor. He was followed by Gerecke, then Keitel, who was handcuffed to a guard. They walked into the courtyard that separated the cell block from the prison gymnasium where the gallows had been erected hours earlier.

When Andrus reached the gymnasium door, he knocked to let those inside know the next prisoner was ready. A military police officer opened the door, and Andrus led the other men in. Looming ahead of them, just to the left, were two black gallows, which, in the words of the lieutenant in charge, were “huge, foreboding and hopelessly out of place next to the basketball hoop at the end of the chamber.” A third gallows, held in reserve in case one of the other two failed, stood to the right. A curtain next to it hid eleven wooden coffins.

Left of the main gallows, the four tribunal judges sat at folding tables, and near them, at four other tables, were eight members of the press. Keitel’s eyes went instinctively to the first gallows, where he saw a rope, taut and twisting. He knew Ribbentrop was dying on the other end. Two MPs took Keitel by the arms, and Gerecke followed as they stood Keitel before the tribunal. The judges asked him to state his name.

“Wilhelm Keitel!” the general said, loudly and clearly.

He then turned on the heels of his gleaming black boots and walked briskly up the thirteen steps of the second gallows. Gerecke followed him up, and the two men looked at each other. Gerecke began a German prayer he had learned from his mother. The chaplain knew Keitel’s mother had taught him the same verse as a child, and the general joined Gerecke in prayer.

The prayer was just one thing the two men had in common. Brunswick was another. Keitel had been raised on a farm outside Brunswick in central Germany, and Gerecke’s great-grandfather had left that city when he sailed to America. Keitel was ten years older than Gerecke, but both men had been brought up on farms, and both had married the daughters of brewers. During the year of the trial, Gerecke and Keitel had become close. Gerecke found that Keitel was always “devotional in his bearing” when the chaplain visited his cell. He found the field marshal penitent and “deeply Christian.” Keitel was interested especially in hymns and verses from scripture that dealt with the evidence of God’s love for man, and man’s redemption from sin through Christ’s death on the cross.

Gerecke was very slow to give Holy Communion to a new, or returning, Christian. He needed to be convinced that a candidate not only understood the significance of the sacrament, but that, “in penitence and faith,” he was ready for it. This was the real reason Gerecke took the Nuremberg assignment. These were men who had spit on the notion of traditional Christianity while promoting an idea that a cleansed Germany would mean a better world and a more pure future. Gerecke believed his duty as a Christian minister was to bring redemption to these souls, to save as many Nazis as he could before their executions. After studying the sacrament during the first months of the trial, Keitel asked Gerecke if he could celebrate Communion under the chaplain’s direction. The general chose the Bible readings, hymns, and prayers for the ritual and read them aloud. He kneeled by the cot in his cell and confessed his sins.

“On his knees and under deep emotional stress, [Keitel] received the Body and Blood of our Savior,” Gerecke wrote later. “With tears in his voice he said, ‘You have helped me more than you know. May Christ, my Savior, stand by me all the way. I shall need him so much.’”

After reaching the top of the thirteen steps of the gallows, Keitel was asked if he had any last words.

“I call on the Almighty to be considerate of the German people, provide tenderness and mercy,” he said. “Over two million German soldiers went to their death for their Fatherland. I now follow my sons.”

A United Press account reported that the field marshal then “thanked the priest who stood beside him.” Then the executioner pulled a lever, and just twenty minutes after Gerecke and Keitel had first kneeled in prayer on the general’s cell floor, Keitel dropped through the platform’s trapdoor.

In the seconds that followed, the only sound in the gym was the creaking of the rope against its huge steel eyebolt at the top of the gallows. Gerecke walked out into the rain to retrieve the next prisoner.

Tim Townsend is the author of Mission at Nuremberg: An American Army Chaplain and the Trial of the Nazis, from which this article was excerpted. Townsend is senior writer/editor at the Pew Research Center’s Religion & Public Life Project. Follow him @townsendreport.

From the book MISSION AT NUREMBERG: An American Army Chaplain and the Trial of the Nazis by Tim Townsend. Copyright © 2014 by Tim Townsend. Reprinted by permission of William Morrow, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.