On November 19, 1863, in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, at the dedication of America’s first national cemetery, on the site of the battle that had turned the course of the Civil War decisively toward the Union, Edward Everett of Massachusetts delivered the keynote address. A former Harvard president and heir to Senator of Massachusetts Daniel Webster as the leading orator of the day, Everett offered an exhaustive account of this battle, comparing it to the Battle of Marathon in 490 BCE, when the Greeks had defeated the Persians and saved democracy. In the presence of the living and the dead (many of the 50,000 or so slain soldiers had not yet been buried), Everett also advanced a detailed constitutional argument for the supremacy of the nation over the states. His “classic but frigid oration,” as New York Tribune editor Horace Greeley termed it, lasted over two hours. It has been almost entirely forgotten. Abraham Lincoln’s “dedicatory remarks” lasted three minutes. Today they are remembered as the “Gettysburg Address,” and the finest speech in American history.

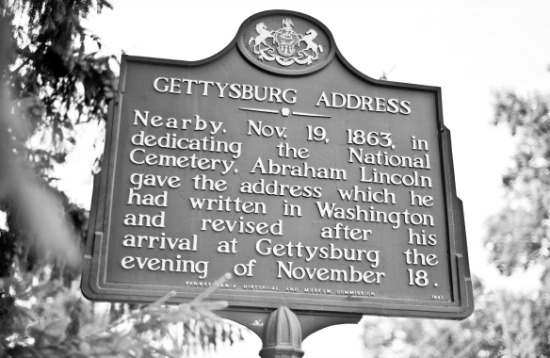

Because the Gettysburg Address is now legendary, legends have grown up around its composition. Some say that Lincoln wrote it on the back of an envelope, perhaps on the train on the way to Gettysburg. Others say he composed it on the fly as Everett was speaking. But he almost certainly prepared a draft in the capital before honing it in Gettysburg.

Most of the speech is dedicated to the men who died there—those who, in Lincoln’s memorable phrase, “gave the last full measure of devotion.” It is not up to the living, Lincoln says, to consecrate this battlefield. Soldiers’ blood has already made this place holy. But it is up to Lincoln and his listeners to ensure that these men did not die in vain. They “gave their lives that this nation might live,” Lincoln says. So it is up to the living to see to it that the United States experiences “a new birth of freedom.”

These sentiments are pitch perfect, as might be expected from America’s most eloquent president. But the underlying message about wartime sacrifice is also the sort of thing a president is expected to say at an event such as this. What Lincoln said about the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution is an entirely different matter.

There is a recurring tension in American thought between the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution. The Declaration is a revolutionary document, but it is also in many respects a radical one, affirming as “self-evident” a host of claims that upon its promulgation would almost certainly have been denied by most colonists. The Constitution is a far more conservative document, a measured product of negotiations among the thirteen states. In short, if the Declaration is an outburst on behalf of liberty and equality, the Constitution is a compromise by committee on behalf of order. Or so it went in the 1700s.

At the heart of Lincoln’s “dedicatory remarks” at Gettysburg is a new interpretation of the Declaration and the Constitution, and of the relationship between them. The first hint of this reinterpretation comes at the start of the opening sentence, when Lincoln dates the birth of the new nation not to the ratification of the Constitution in 1787 but to the promulgation of the Declaration of Independence in 1776. (1863 minus 86 is 1776.) But Lincoln does more than refigure America’s birthday. He distills its project down to one central idea. This bombshell comes in the second part of the first sentence, when Lincoln asserts that the United States, though “conceived in liberty,” is nonetheless dedicated to one and only one proposition: “that all men are created equal.”

In his last sentence, Lincoln offers another reason for the ultimate sacrifice of these men. They have died so that real republicanism might live—“that government of the people, by the people, for the people shall not perish from the earth.” Here Lincoln is borrowing from Daniel Webster and the Transcendentalist/Unitarian minister Theodore Parker, both of whom had defined democracy in similar terms. In so doing, Lincoln is locating U.S. sovereignty not in the states but in its people, reading the federal government as a covenant of people rather than a compact of states. In fact, it was to this end that Webster had presented his formulation of “the American idea” in a debate on states’ rights with Senator Robert Hayne of South Carolina. “Is it the creature of the state legislatures or the creature of the people?” he asked. “It is, sir, the people’s Constitution, the people’s government; made for the people, made by the people and answerable to the people.”

What is Lincoln doing here? First, he is subordinating the Constitution to the Declaration of Independence, which had long stood at the center of his political thought. The Declaration was America’s Genesis, the founding book of the American Bible and the core expression of the aspirations of the American people. It was this text that constituted the nation. According to historian Garry Wills in his book Lincoln at Gettysburg: The Words that Remade America, “Lincoln distinguished between the Declaration as the statement of a permanent ideal and the Constitution as an early and provisional embodiment of that ideal, to be tested against it, kept in motion toward it.” Second, Lincoln is reading the “equality clause” of the Declaration—the self-evident truth “that all men are created equal”—as the heart and soul of this founding expression, and employing equality (a word never mentioned in the Constitution) as a prophetic principle by which the American experience is to be judged. Third, he is, by context and implication, reading African Americans into that clause. They, too, are human beings; they, too, are created equal. Finally, he is reimagining the United States not as a collection of states but as a people. “Up to the Civil War, ‘the United States’ was invariably a plural noun: ‘The United States are a free government,’” Wills explains. “After Gettysburg, it became a singular: ‘The United States is a free government.”

But this Gettysburg revolution did not simply put the American people over and above the states and the spirit of the Declaration before the letter of the Constitution. In practical terms, it elevated the Gettysburg Address above the Declaration. Here the same eyes Lincoln used to gaze over the battlefield became the eyes through which subsequent generations read the Declaration. “For most people now,” Wills concludes, “the Declaration means what Lincoln told us it means.

This new gospel of Gettysburg—a new version of the “good news” of the American story—had huge implications, of course, on the question that was above all other questions at the time, since the Constitution would seem, on any simple reading, to favor slavery, while the “self-evident” truths of the Declaration seem to protest most emphatically against it. But Lincoln did not take up this question at Gettysburg. Neither did he address God—a role relegated to the House chaplain, the Reverend Thomas Stockton, and the Reverend Henry Baugher, president of Gettysburg College. In fact, Lincoln’s working draft did not mention the Almighty. But he added the words under God under the impress of the moment, and then to subsequent copies he produced. Roughly a century later, in 1954, this last-minute insertion would become a winning argument for adding “under God” to the Pledge of Allegiance.

After Lincoln finished speaking, he was met, first, with a hushed silence and then with “immense applause.” Not everyone in attendance was happy, however. The Chicago Times complained about the president’s “silly, flat, and dishwatery utterances,” while the Harrisburg Patriot and Union allowed itself to hope “that the veil of oblivion shall be dropped over [Lincoln’s remarks] and that they shall no more be repeated or thought of.” The Massachusetts-based Springfield Republican, however, got its first draft of history right: “His little speech is a perfect gem, deep in feeling, compact in thought and expression, and tasteful and elegant in every word and comma.”

What this “perfect gem” did was define the Civil War to succeeding generations, and in the process to redefine America. Still, many took exception, both before and after his 1865 assassination, to Lincoln’s interpretations of the war and the nation. The Democratic Chicago Times called his address “a perversion of history so flagrant that the most extended charity cannot regard it as otherwise than willful.” Others insisted that the Constitution, not the Declaration, was the law of the land and the basis for the national compact. Many Northerners, chafing at any suggestion that the Civil War was fought to secure racial equality, insisted that the purpose of the war was to preserve the Union. Who said that blacks were heirs to the Declaration’s promises?

This debate has never been settled, but the legend of the “Gettysburg Address” has swelled over time. The popular elementary school readers of the McGuffey brothers started to include it in the 1890s, and it was first cast in bronze in 1896. By the start of the twentieth century it had become American scripture—“the nation’s political Sermon on the Mount.” Over the last hundred years, Americans have invoked the Gettysburg Address to justify all sorts of causes—new wars, of course, but also Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s war on poverty, the Equal Rights Amendment, and the civil rights movement. In 2011, economist Joseph Stiglitz married Lincoln to the Occupy Wall Street movement with a Vanity Fair essay in runaway income inequality called “Of the 1%, by the 1%, for the 1%.”

The “Gettysburg Address” has also been used to chasten America. In 1984 the South African Archbishop Desmond Tutu blasted the United States for abstaining from a U.N. Security Council vote condemning apartheid in South Africa: “I believed, naively perhaps, that the United States lived by the precepts of the Declaration of Independence and the Gettysburg Address.” In 1985, the Soviet state newspaper Pravda, noting that the large corporations that had picked up much of the $12.5 million tab for President Reagan’s second inauguration would expect their generosity to be repaid, said the U.S. was becoming “a government of millionaires, for millionaires and by millionaires.”

As the civil rights movement moved from success to success in the 1960s, Lincoln’s views of the Constitution, the Declaration, the Civil War, and the origins and ends of American came to predominate. Or, to be more precise, an even more audacious interpretation of the Declaration’s equality clause triumphed, because Lincoln, who in his famous debate with Stephen Douglas stated plainly, “I am not, nor ever have been in favor of bringing about in any way, the social and political equality of the white and black races,” never imagined the sort of racial integration that came with the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

During the Reagan Revolution of the 1980s and beyond, conservative advocates of states rights and an “original intent” approach to Constitutional interpretation challenged the Gettysburg gospel, rejecting Lincoln’s elevation of equality to the guiding principle of American life. Echoing earlier critics, these conservatives now argue that the Declaration did nothing more than declare thirteen independent colonies independent from the British crown. It did not found a new nation; the Constitution did that. Moreover, the equality clause in the Declaration could not possibly have created a national commitment to realize equality for all. “All men” could not have meant “all men” to the founders, since the vote was kept from slaves, women, and the landless. Lincoln’s “second founding,” in short, lured the country away from first principles and toward untold dangers. Far from the pinnacle of American political thought, these critics argued, the Gettysburg Address is a nadir.

Despite these criticisms, the Gettysburg Address is now widely recognized as the greatest American speech, challenged only by Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream,” which shares with it not only a vision but also soaring rhetoric and a historic moment appropriate to the task. In recent years, the most quoted phrase from the Gettysburg Address, perhaps because of its resonances with resurgent evangelicalism, is “a new birth of freedom.” Bob Dole, Jack Kemp, and Steve Forbes used this phrase in their Republican campaigns for president, and Ronald Reagan used it at least ten times during his presidency. In 2009, the theme of the inauguration of America’s first black president, Barack Obama, was “A New Birth of Freedom.”

THE GETTYSBURG ADDRESS

Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent, a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.

Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure. We are met on a great battle field of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of that field, as a final resting place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this.

But, in a larger sense, we cannot dedicate—we cannot consecrate—we cannot hallow—this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it, far above our poor power to add or detract. The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here. It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us—that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion—that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain, that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom—and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.

This version is based on the so-called Bliss copy, made for Colonel Alexander Bliss, and now located in the Lincoln Room of the White House. This copy is the only version Lincoln signed.