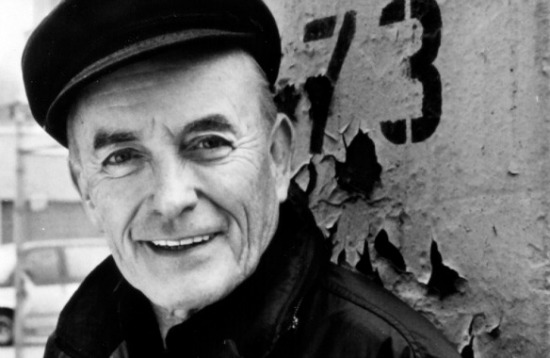

Father Andrew Greeley, who died in May at the age of 85, used to joke that he would be remembered as the Catholic priest who wrote sexy novels. As it happened the obituaries written for him all did refer to it. This apparent paradox was evidently the most compelling of the contradictions said to characterize Greeley’s life, or at least it was the most salacious, conjuring up as it did the old fantasy of the cleric as clandestine libertine. But there were others: here was a sociologist who wrote books of prayers to a God he took as really present; a priest who was also a crime novelist; a university professor who loved the life of Catholic parishes; and an “outspoken”—the most common adjective used to describe Greeley in the obituaries—critic of the Catholic hierarchy with unshakeable hope in the Holy Spirit at work in the church.

Greeley’s long and productive life was characterized by real and multiple incongruities. He came up in mid-twentieth century Chicago Catholicism, a seminarian at Mundelein, serving first as a parish priest in the late 1950s before going on to train as a social scientist at the University of Chicago. He received his doctorate in 1962, the same year the first session of the Second Vatican Council convened in Rome. Catholic Chicago and Hyde Park might as well have been different planets for all they had to do with each other in those years. The vein of incongruity that runs through Greeley’s life begins here, in an existential and religious breach mapped onto Chicago’s topography; perhaps this is why Greeley was such a passionate wanderer of the city all his life, as if he wanted to walk out connections that were otherwise so elusive. The question confronting him in these transitional years in American Catholic history—a transition Greeley faithfully charted in his research—was what the relationship would be between the Catholic imaginary in which he had been formed and the sociological imagination in which he was being formed, a version of the question many Catholics entering the secular academy confronted in this time. Because Greeley was compelled to work this through so intimately in his mind, heart, and soul, as he traversed the city he loved so dearly, his life invites a closer look at what “Catholic” means when it is prefaced as an adjective to an academic discipline, as in “Andrew Greeley, the Catholic sociologist.”

As it happened the young Father Greeley was laying the foundations of his life’s project just as the prelates in Saint Peter’s were trying to figure out a new relationship between the church and the modern world, on the other side of alienation and rejection. The Council’s major statement on the church, Lumen Gentium, promulgated by Paul VI on November 21, 1964, called the life of the church on earth a “mystery,” which in Catholic theology means a sacred reality lived but not fully comprehended. The church is both visible and invisible, “hidden with Christ in God,” in the words of the text. This does not mean there are two churches. Just as Jesus was both fully human and fully divine, so too, says Lumen Gentium, the church “as the visible assembly and the spiritual community … the earthly Church and the Church enriched with heavenly things” are not separate but “form one complex reality which coalesces from a divine and a human element.” This visible/hidden community, now defined as the people of God on pilgrimage in the world, was to be found in engagement with its times in an open, humble, and discerning spirit. Catholicism, in other words, is both an ontological reality and a question for empirical research. What may be glimpsed of “the church enriched with holy things” in the ordinary lives of Catholics making their way in society?

This is the mystery/sociological understanding/theological truth that Father/Professor/Detective/Andrew Greeley/Blackie Ryan [his forensic alter ego] was in search of in his fiction/sociology/devotions/parish work/sleuthing/pastoral writing. Greeley’s productive and generative life was poised at the point of coalescence of the visible assembly and the spiritual community that Lumen Gentium identifies. The integration of the theological and the sociological, the Catholic imaginary and the sociological imagination, gave Greeley’s work its conceptual vitality as well as its moral force. Coalescence here may be taken as a cognate of what William James called the “more” of religious experience. This is not to say that Greeley lost sight of the protocols and standards of sociological research; nor did he speak sociologically when a pastoral response was called for; he did not turn away from the venality, contradictions, and corruptions of Catholicism; and he did not confuse storytelling with data analysis. But Greeley was confidently and generously one person, one priest, and one scholar, despite all the slashes above, and when he spoke or wrote out of the coalescence-that-is-one-reality he made the boundaries of his various projects porous to each other, in a coalescent empiricism.

Greeley studied Catholic adolescents in the United States sociologically in the tumultuous years of the 1960s and 1970s, for example, and at the same time he published pastoral articles in popular Catholic magazines offering counsel as a priest to young people and their parents that was informed by his empirical research. He charted the suburbanization of white Catholicism while calling the children and grandchildren of European immigrants to account for fleeing their moral and social responsibilities as Catholics to the cities. He wrote eloquently of the role of the Virgin Mary in Catholic history and culture and he was unabashedly devoted to her. He recorded the proliferation of new devotional practices among Catholics in the 1970s in a spirit that was attentive both to the spiritual hunger of the period, as a social scientist, and to its spiritual dangers, as a priest. Throughout his long and productive life he wrote theology as well as sociology, alternating one genre with the other.

Coalescent empiricism offers another way of thinking about the sex scenes in Greeley’s fiction (what anti-Andrew-Greeley-Catholics call his “pornography”). Greeley was writing as much as a priest and confessor as he was a novelist in these books, with a sociologist’s attunement to the social realities impinging on human relationships. For this reason his defenders’ argument that the partners in his sex scenes are always married misses the point. Priests were supposed to know about all manner of licit and illicit sex. They were trained in the seminary to listen with understanding and compassion to people’s accounts of their sexual transgressions in all their multifariousness. (That the appearance in the same paragraph of the words “priest” and “sexual transgressions” probably makes some readers squirm is yet more proof, if any was needed, of how deeply all the bishops, diocesan administrators, nuns, parents, and parishioners who in complete complicity with evil covered up clerical sexual crimes so utterly failed the people of God.) Sexuality in Greeley’s novels has as much to do with the dilemmas of human intimacy, its social intricacies and its grief, as it does with pleasure. Greeley’s romances inherited and expressed a Catholic vision of human embodiment that fully acknowledges the ambiguity and pain of human relationships as well as the beauty, as it holds out the promise of forgiveness.

Because he saw the church clearly in all its social and moral imperfections, without apology, Greeley is commonly thought of as a liberal Catholic. But this says more about what has become of Catholicism over the past quarter of a century than it does about him. Catholics find themselves confronted today by the stark choice of either submitting obediently and without question to what their prelates tell them to do and to think or else leaving the church. Such is the message of the Vatican’s persecution of American nuns. But Greeley’s Catholicism—the Catholicism he lived and the Catholicism he studied—was too capacious to be constrained within the arid polarities of liberal/conservative polemics. He modeled a way of being Catholic that was at once free in conscience and faithful.

Early on in his public career, in 1967, Greeley joined Daniel Callahan, L. Brent Bozell, George Shuster, Jacqueline Grennan, and Bishop Robert Dwyer for a discussion hosted by the National Catholic Reporter on “issues that divide the church.” The proceedings were published that same year as a small book. The battle lines were sharply drawn from the start. Bozell, who was William Buckley’s brother-in-law and a co-founder of the National Review, set the tone. He relentlessly taunted the others, in particular Grennan, a former nun who was at the time president of Webster College. Throughout what must have been a tedious and unedifying day for him Greeley spoke up—not in defense of what Bozell was caricaturing as Catholic liberalism, still less to chart a middle course (a task that fell to Bishop Dwyer), but to bring the conversation down to earth, to the places where Catholics lived. Polemicists insist that some particular account of the visible church, their own, in one moment of time, is the true church. Greeley would not tolerate such presumptive closure.

Nor did he sign on to the resurgent Catholic triumphalism of the 1980s and 1990s. Lumen Gentium speaks of the church possessing a sanctity that is “real but imperfect,” and it was in this spirit that Greeley functioned as a public intellectual within Catholicism. He had been formed as a priest, scholar, and citizen in the Catholic tradition, a polyvalent inheritance of theology, ritual, aesthetics, moral and political philosophy, devotionalism, and spirituality. Catholicism has developed over centuries in dynamic engagement with the world; this is not the story of the movement of a hermetic perfectionist sect through time. Greeley critically engaged the church from within the heart of its tradition, speaking out of the places where Catholicism in its imperfect holiness met and continues to meet the world.

This was risky. Greeley’s various clashes with the hierarchy are well known. But the more intimate vulnerability of his position becomes evident in a less obvious context. He was one of the first public figures in the church to speak out clearly and forcefully against diocesan administrators who protected pedophile priests. By all accounts he was also generous in his moral and financial support of fledgling survivor organizations. Chicago was an epicenter of the movement. I have heard from people who were there that at an early public gathering of survivors Greeley became visibly distressed when justified and necessary criticism of administrative malfeasance and legitimate anger at pedophile priests turned into a generalized hatred of the church and contempt for all priests. He went to the meeting as a priest, in his collar and black suit, to show a priest’s solidarity with those abused by priests. But his critical faithfulness seems to have made nearly everyone unhappy with him in this instance. It was not an unfamiliar position for Greeley to be in, but there is no reason to think he enjoyed it. There is an expression among Catholic liberals of my generation that to be a critic of the church “you have to look good on wood.” Martyrdom was not Greeley’s style.

The most challenging thing then about Greeley’s vision of the church is that it is a fully and courageously sacramental ecclesiology, meaning that even in its imperfect holiness, the church is still the church, because the visible church, with all its evident complicity in human failure, is not identical with the hidden life of God within. Greeley was a sociologist who had the perspective of the ages. I confessed to him in one of our last conversations that I was in despair over the church. How could the Vatican forbid the distribution of condoms in the midst of a global AIDS epidemic? How could bishops and diocesan vicars reassign pedophile priests over and over to parishes and schools knowing full well these men would go on to molest and rape other children? I saw no reason for hope. Greeley encouraged me to trust the Holy Spirit. “She” will surprise you, he said.

Thinking about this comment in the years since, or rather holding on to it as a protective talisman in dark times, it seems to me that the Holy Spirit named or embodied for Greeley the promise that every now and then the visible and the hidden realities of the church might touch in what the poet Christian Wiman calls “fugitive instances of apprehension.” The Holy Spirit is the sign and the presence of coalescence. Greeley, the priest and sociologist, kept a keen eye on the people of God for evidence of this grace.

Robert A. Orsi is Professor of Religious Studies and History and the Grace Craddock Nagle Chair in Catholic Studies at Northwestern University. He serves on the Editorial Advisory Board of Religion & Politics.