Universal History Archive/Getty Images

Last Tuesday, Andrew Sullivan’s post at The Daily Beast highlighted what he believes to be the double standard the American media has applied to the racially charged sermons delivered by President Obama’s former Pastor Jeremiah Wright—replayed in a constant loop in 2008—and the relatively scant coverage the history of racial exclusion Mitt Romney’s Mormonism has received in 2012.

“It is a fact,” Sullivan writes, “that Mitt Romney belonged to a white supremacist church for 31 years of his life … which retained white supremacy as a doctrine until 1978.” With this in mind, Sullivan asks his readers to engage in a thought experiment: “[C]an you imagine the outrage if Obama had actually been a part of a black supremacist church?”

Sullivan intended to provoke. And provoke he did. At Religion Dispatches, Joanna Brooks noted that while he got many details wrong about race and Mormonism, “Sullivan is right to point out that there is a tremendous double standard at play” when it comes to linking Wright to Obama and Mormonism to Romney. Yet in private, other Mormons—even those sympathetic to Sullivan’s analysis of their church’s troubling past—thought the timing of the piece was more provocative than its content. Sullivan’s post was more a manufactured “October surprise,” or even “blatant political demagoguery,” as one Mormon politico told me, than serious media criticism. At The American Conservative,this was more or less Rod Dreher’s assessment. While sharing Sullivan’s “disgust for the legacy of the anti-black theology [of] the Mormon church,” Dreher asserted that Sullivan “raises this because the election is very, very close, and his candidate, Obama, is in trouble.”

I too found Sullivan’s piece to be provocative. But unlike Dreher, and some of my Mormon friends, the lessons I take from the questions that Sullivan raises have less to do with the last two weeks of this presidential campaign, and more to do with the past four years of the Obama era.

Here are three such lessons.

First, the Obama presidency, and the nomination of Mitt Romney, have led to an unprecedented confluence of the issues of race, religion, and the identity of the American president. Sullivan is right to ask why Obama was required to repudiate Wright if he hoped to get elected, while Romney has not felt personally compelled—nor publicly forced—to do more than follow the long-established position of the church fathers in Salt Lake: to let the 1978 revelation, which opened up the Mormon Church to full black membership, “stand on its own.”

I think there is a racial component to the incongruity in the way the media has treated Obama and Romney’s faiths. To be sure, both Romney’s Mormonism and Obama’s black liberation theology-infused Christianity still exist—in the minds of many Americans—outside the religious mainstream. Yet when it comes to “10 a.m. on Sunday morning [being] the most segregated hour of the week,” as Martin Luther King Jr. is credited with saying, Mormon exclusion of blacks from full membership is certainly not uniquely Mormon. Instead, it belongs to a history that most American Christian communities have had to contend with. Wright’s powerful—and poorly understood—critique of the legacy of institutional racism was too direct, too on the nose, for many Americans—including the Americans whose votes Obama needed to become president.

This ties in with the second lesson: a dire need for all Americans to be religiously literate, as both Stephen Prothero and Diane Moore have argued. Sullivan bases his criticism of race and Mormonism on a rhetorical analysis of the Book of Mormon. Yet, the Book of Mormon’s racialized language does not describe African Americans, but instead “Lamanites,” whom Mormons believe to be the ancestors* of modern-day Native Americans. Sullivan thus mistakenly reads the Book of Mormon through the lens of the American racial binary of “black” and “white,” which signifies “African” and “European.”

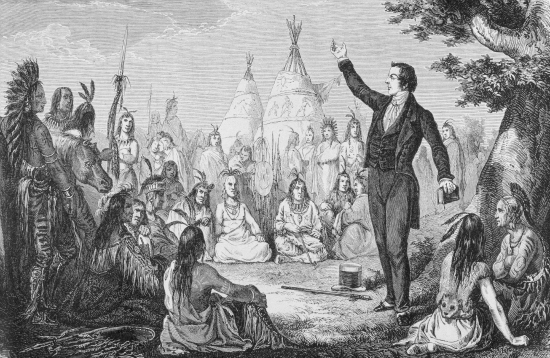

The roots of Mormon racial exclusion lie elsewhere, in the standard nineteenth-century biblically-based justification for slavery and segregation. The founder of Mormonism, Joseph Smith Jr., did welcome some African Americans into his early community. Yet Smith also accepted the widely-held view that African Americans were the “cursed” descendants of the biblical anti-heroes, Cain and Ham. Though in the twentieth century, a specifically Mormon justification for the ban developed, the origins of Mormon racial exclusion are more American than Mormon.

The same need for religious literacy exists for a better understanding of Jeremiah Wright’s fiery rhetoric. Wright’s inversion of “God bless America” to “God Damn America,” is shocking. But it is meant to be so. Black liberation theology challenges the status quo by asserting that Jesus is on the side of the oppressed. After all, Wright asserted (in a section of his infamous sermon that rarely got much air time), “America failed [African Americans]… She put them in chains, the government put them on slave quarters, put them on auction blocks, put them in cotton fields, put them in inferior schools … God damn America, as long as she tries to act like she is God, and she is supreme.” Wright’s phrase “as long as” is the fulcrum of the sermon. In the classic jeremiad tradition, Wright calls America back to its promises of equality and justice for all, in the hope that its past and current oppression of African Americans is temporary, and not intrinsic to the nation itself.

Finally, and briefly, let me add a third lesson: In terms of failing to live up to their own standards, religious systems are more like political (or secular) ones than we would like to believe. Religion and politics are institutionally constituted, and governed by citizens, politicians, and believers—in other words, by fallible human beings. The fact that the systems (and people) that shielded the clerics of the Catholic Church who abused children resemble what went on at Penn State (and now, we are learning, in the Boy Scouts) should not be a surprise. Institutions, be they big-time churches, big-time football, or big-time scouting, are structured to self-perpetuate. This means that too often we must rely on courageous individuals to blow the whistle when institutions fail their most vulnerable.

But religion, as both believers and our own Constitution point out, is special. And because faiths assert a relationship with God, with the “transcendent,” with a “holy other,” however individual faiths describe it, we expect more from our religious institutions. Here I take my lessons from my friend, Jerri Harwell, a black Mormon woman who joined the LDS Church in 1977, just months before the priesthood ban was lifted. As a new convert, Jerri learned quickly that the Mormon Church forbade her from full membership. Yet her prayers told her that the exclusion of blacks was not God’s will, “but the will of men.” Still, today some 34 years after the revelation that allowed full church membership for blacks, Jerri understands the LDS Church to be a “denomination,” and thus prone to failure. But because she knows the church is imperfect—an understanding rooted in pragmatism not cynicism—she is empowered to criticize it, and challenge it to live up to its own promises.

Let that be a lesson to us all.

Max Perry Mueller is associate editor of Religion & Politics.

*Correction: The article originally used the word “descendants” when “ancestors” was intended.