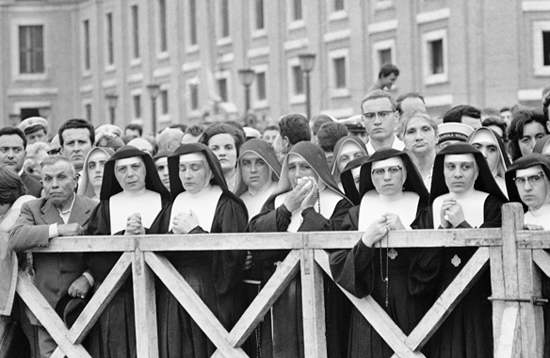

(AP Photo)

In April, the Vatican censured the Leadership Conference of Women Religious (LCRW), a body that represents more than 80 percent of American sisters. After a two-year investigation, the Vatican’s Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith (CDF) alleged that the LCRW had promoted “radical feminist themes” in its programs, had encouraged models of leadership that privileged dialogue over clear exertion of authority, and had tolerated dissent against bishops and other Church officials. In its formal “Doctrinal Assessment,” the CDF also charged that American sisters had failed to give sufficient attention to the Church’s opposition to abortion, euthanasia, and homosexuality, focusing instead on issues of social and economic justice. An archbishop and two bishops will now oversee the LCWR’s “renewal,” attempting to reform the group to align more consistently with what Rome deems to be proper doctrine. Sister Pat Farrell, president of the LCRW, has called the charges inaccurate and unfair and has asked the Vatican to engage in “open and honest dialogue” about the censure and the involuntary renewal process.

In an interview with CNN about the criticisms, author and radio host Sister Maureen Fiedler invoked the Second Vatican Council in defense of her American Catholic sisters and the priorities they hold dear today. She shifted the focus away from politics and toward the history and structure of the church itself. “What’s really at stake here in the larger significance of this [conflict] is the future of the church,” Fiedler said: “whether we’re going to go back to the old church before the Second Vatican Council, which was male and dictatorial and not collaborative, obsessed with issues of sexuality, or whether we’re going to go forward with what the Second Vatican Council called us to, which was collaborative leadership and dialogue and a church where the laity really have a place—and a place where social justice issues are in the forefront of the agenda that we’re carrying forward.”

Sister Fiedler’s appeal to the Council was not a casual reference. Rather, her invocation of the Second Vatican Council goes to the heart of the current conflict between American sisters and the male hierarchy of the church, and it illuminates both what caused the current conflict and what is at stake for both sides in its resolution. Bluntly, if one party has departed from the definition of Church promulgated by the world’s bishops during the Second Vatican Council, it is not the nuns.

THE SECOND VATICAN COUNCIL (sometimes called Vatican II) was a major meeting of the world’s bishops that took place in Rome between 1962 and 1965. Pope John XXIII called the bishops to Rome to facilitate what he termed “aggiornamento” or modernization, literally bringing the church up-to-date. At the Council the bishops wrote, debated, revised, and voted to approve 16 separate documents that addressed topics like the nature of the church, its relationship to the world, the liturgy, ecumenism, and religious freedom.

Most people associate Vatican II with liturgical revisions that changed the mass from Latin to the vernacular langue of the local population, but the Council also sparked deeper systemic reforms in the ecclesiology and self-definition of the Catholic Church. In Lumen Gentium, the Council defined the church as “the Pilgrim People of God,” a phrase that underscored the processual and inclusive nature of the church and defined the Catholic faith as an ongoing journey. This was in contrast to longstanding assumptions that equated the church with the male hierarchy of priests, bishops, and the pope in their role as arbiters of doctrine and morality. Gaudium et Spes affirmed that each human person posses inherent dignity. It also emphasized the foundational solidarity of the Catholic Church for individual persons—and indeed the whole human family—especially those who suffer from poverty, injustice, and war.

Vatican II also addressed the need for aggiornamento or modernization in congregations of vowed religious. The conciliar document Perfectae Caritatis called for sisters to revise their missions, rules, and constitutions to make religious life more relevant to the modern world. Sisters were to be guided in this process by the gospel and through reflecting on the spirit of those who founded their congregations. In successive directives, the Vatican instructed sisters about the proper process for these revisions and established a period where sisters could experiment with changes to established norms in dress, lifestyle, leadership, and ministry.

American sisters responded obediently and often enthusiastically to the immense tasks imparted by the Council. Through the late 1960s and early 1970s, sisters read and debated theologies of religious life and immersed themselves in the deep histories of their congregational founders. They reflected on the meaning of their vows and the role of religious consecration in contemporary society. They formed committees to address different facets of religious life, performed multi-year self-studies, conducted surveys of their entire membership, wrote detailed reports about their findings, and held open chapter meetings where sisters talked freely about the pain and promise of vowed life. In the end, American sisters reached a working consensus about the form and direction vowed religious life should take in light of the Second Vatican Council.

The LCWR is a direct embodiment of these reforms. The Leadership Conference originally was named the Conference of Major Superiors of Women’s Religious Institutes (CMSW). Formed in 1956 in response to Pope Pius XII’s call for the vowed religious to form national organizations, the CMSW’s founding statutes defined its purpose as “the promotion of the spiritual welfare” of American sisters. Following Vatican II, many congregations concluded that true Christian community honors the inherent dignity, ethical autonomy, and moral conscience of its members rather than requiring unquestioning obedience to external authority. By 1971 members believed that the title “superior,” with its connotations of hierarchy and autocracy, no longer reflected the new understanding of authority that had emerged in congregations of sisters through their renewal process. Changing the name of the organization to the Leadership Conference of Women Religious, sisters were signaling that they saw leadership as a prayerful, participatory, consensual, and democratic process among sisters rather than an embodiment of monarchical authority in a single person.

Aggiornamento was not easy for American sisters. The process of implementing the mandates of the Second Vatican Council was costly in both time and resources. The airing of diverse ideas about the direction of their collective life sometimes strained the cohesion of religious communities. A significant number of sisters left religious life in the tumultuous period of adaptation and renewal. Most congregations interpreted these challenges as necessary growing pains, a natural result of trying to adapt medieval institutions to the twentieth century. In her influential study of modern religious life, Finding the Treasure: Locating Catholic Religious Life in a New Ecclesial and Cultural Context, Sister Sandra Schneiders compared the conciliar adaptation of sisters to the evolution of prehistoric dinosaurs into modern-day birds. Both dinosaurs and preconciliar convents were large and powerful but ultimately ill-adapted to dynamic environments. Birds and congregations of modern sisters may be less imposing, but they are swift, svelte, adaptable, and much better suited to the contemporary world than their predecessors.