(Used by permission of University of California Press)

Making Chastity Sexy: The Rhetoric of Evangelical Abstinence Campaigns

by Christine J. Gardner

University of California Press, 2011

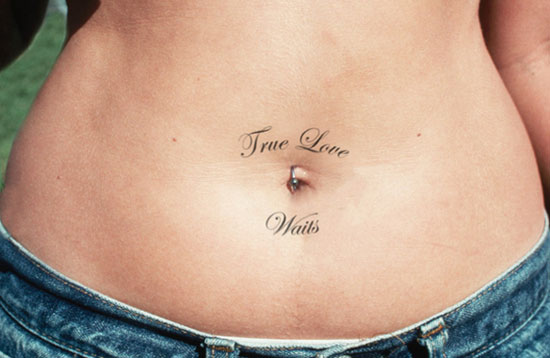

When it comes to adolescent sexuality, more than the hormones rage. The culture wars still infect questions of how best to teach kids about sex and how to prevent disease, pregnancy, and heartbreak. For conservative Christians, the answer has been relatively straightforward: teach them to just say no. Since the mid-90s, abstinence organizations like True Love Waits, The Silver Ring Thing, and Pure Freedom have attempted to provide teenagers with an alternative to hyper-sexualized popular culture by encouraging chastity until marriage. By hosting live events, Bible studies, and selling popular purity rings, all three of these organizations remain strong, claiming to have reached millions of youth, with tens of thousands of new participants added at dozens of events held nationally and internationally each year.

In Making Chastity Sexy, Christine Gardner, a communications professor at the evangelical Wheaton College, examines the rhetoric of these three abstinence organizations, analyzing their books, pamphlets, Web sites, and events, as well as interviewing leaders and followers. In the end, she determines that the old adage is true: Sex sells. Only this time, sex even sells abstinence.

Gardner’s principal critique of American chastity organizations is their capitulation to the “sexy” overlay of popular youth culture. These organizations aim to be, and are, popular and successful among young people in part because they add a sexual charge to the idea of abstinence. “Put this ring on,” says the founder of The Silver Ring Thing to a large gathering of young women, “and I guarantee you that there are young men here who will fall in love with you tonight.” Organizers argue that chastity is sexier than its alternative, more ultimately alluring and more gratifying. A young person says no now so that he or she can say yes to marital satisfaction later. The formula goes: early restraint plus godly partner equals great marital sex. Organizers promise that “good sex” is worth waiting for, and that those who wait will be well rewarded by God in sexually fulfilling marriages.

Gardner notes two problems with this kind of argument. The first is that organizers are making a false promise. They, of course, have no way of knowing that marital sex will be full of pleasure, “as God intended,” for everyone who signs a pledge or dons a ring. Chastity culture is, at heart, a sales pitch; and as a sales pitch, it promises what it cannot possibly deliver. In one particularly painful anecdote, Gardner interviews a young man who waited to have sex; his wife did too and even gave him her purity ring as a wedding gift. But the marriage did not come with “great sex.” “We thought it would be something intimate, something comforting that we could share,” he told Gardner, adding, “It has become a complicated thing, more painful and divisive.” Soon after the wedding, his wife discovered deeply buried memories of sexual abuse, and his life as a married man lacks the easy intimacy he had imagined. This wasn’t the program he signed up for.

Gardner’s second objection approaches the subject almost theologically: when chastity is sold as sexy and alluring, that message inherently obscures the message that a Christian life is a life of sacrifice rather than self-gratification. “The individualistic what’s-in-it-for-me approach may resonate with today’s teenagers, promising great sex and future marriage as a reward for abstinence, but the persuasiveness of that argument subtly shifts the nature of evangelicalism away from sacrifice and suffering to self-gratification,” Gardner writes. In other words, the chaste life is imagined as one that can most benefit the self—leaving a person healthier and happier—as opposed to a life where one surrenders the self to God or sacrifices oneself for the good of others.

One of Gardner’s key questions, and a useful one, is: can the abstinence movement be empowering for young women? She finds that empowerment rhetoric is very much a part of these campaigns, in what becomes an uneasy alliance between feminism and the image of fairytale romance presented. Young women are encouraged to assert control over themselves and their relationships. Even modesty in dress, once an issue of submission, is re-written as a form of power. “A true princess,” writes Gardner, echoing the rhetoric of Pure Freedom, “is one who chooses modesty instead of surrendering her sexual power to men through immodesty.” Men are depicted as being weaker beings sexually. Chastity rhetoric for men focuses on men controlling their errant impulses. Chastity rhetoric for women focuses on women controlling men’s errant impulses. It remains a tangled double standard with very rigid understandings of male and female sexuality. But ironically, the goal, at least rhetorically, is no longer to deliver untainted females into male hands, but rather to give young women more say over their futures. In turn, young evangelical women appear less willing to define themselves solely in terms of their future partners, a sign of what’s possibly to come for conservative Christianity’s ongoing negotiation with contemporary culture.

Gardner deals only lightly with the cultural changes in which chastity rhetoric has emerged, but these cultural changes are significant. The average age of first marriage is now 28.7 for men and 26.7 for women. This means that the commitment that young people make when they try to combine an old world sexual standard to a new world reality is greater than the commitment made by their parents or grandparents. A commitment to abstinence made at age 15 will look quite different at age 25 or 30. Nearly 90 percent of adults have sex before marriage, and 80 percent of conservative Protestants do. This is not to say that people do not make and keep these commitments—only that when they buy into abstinence campaigns, that pledge will shape considerably more of their lives than it would have in previous eras.

If chastity is to be made sexy, then sex sells more than just the idea of abstinence—it peddles a whole line of purity products. From fashion shows for modest styles to bumper stickers, T-shirts and silver rings, contemporary abstinence is as much about economics and image as it is about a particular choice made in private settings. Riven through the rhetoric of abstinence is the idea that lifestyle choice requires appropriate purchases. Dannah Gresh, the founder of the abstinence group Pure Freedom, identifies abstinence with self-esteem and self-esteem with buying things. In her book And the Bride Wore White: Seven Secrets to Sexual Purity, Gresh writes, “God says you are a princess … You must present yourself as you would priceless china.” She then details this with specifics of “the royal wardrobe” as well as advice about personal conduct. On the Silver Ring Thing website, you can buy books, videos, t-shirts and jewelry, and participants confirm their commitment with the purchase of a $20 ring.

This conflation of consumer culture and abstinence in part leads Gardner to Africa, where she wonders if abstinence education, U.S. style, can be exported. While the bulk of her work is with U.S.-based organizations working with American teenagers, she adds two chapters, based on a short time in Africa, about abstinence education in Rwanda and Kenya, where programs are shaped by American organizations but not identical to them. Gardner does not really spend enough time with these groups and their leaders in Africa to unravel the cultural and social nuances of their work. In some ways, Gardner’s chapters on abstinence in Africa—one based on interviews and observations in classrooms and the other on arguments made about condom usage and the AIDS crisis—seem to be part of a different, yet unwritten, book. While a great deal more depth is needed to understand what Gardner observes, the chapters serve the important role of reminding the reader that abstinence organizations have a global reach and that interactions between cultures are never a simple matter of export and import.

The most contradictory facet of the book is Gardner’s own positioning vis-à-vis the purity movement. At times, she plays the role of critical observer but more often than not, it is clear she shares, at least to a degree, these organizations’ goals and their assumptions about the nature of Christian marriage and the value of abstinent young adulthood. She accepts the logic that sex outside marriage leads primarily to heartbreak. Though she tries to get past the purity movement’s depiction of secular teens as primarily pleasure-seeking and hedonistic, she remains attached to the notion of virginity as a precious gift bestowed to another only in marriage. She even goes so far as to use, without challenge, Pure Freedom’s “broken teacup” metaphor in talking about young people who have had sex. She is left, then, with cataloging the ways that young people might not fit the “chaste singlehood until marriage” ideal. “Second virginity,” homosexuality, sexual abuse, and life-long singlehood are treated as exceptions to an otherwise good rule.

These shared presumptions both benefit and limit the book. On the one hand, Gardner perceives and reconstructs her interviewees’ worldviews with depth because of her familiarity with them. On the other hand, she does not give the context in which these campaigns are situated. We are left to believe that the organizations’ construction of a destructive secular culture bent on disease and personal disaster is an accurate portrayal of the world against which they stand. A greater consideration of other factors—the delay of marriage, studies on marital happiness, cultural change regarding homosexuality, and gender roles for men and women—would have helped Gardner capitulate less to these purity organizations while also providing another layer of understanding.

In Making Chastity Sexy, Gardner proves herself to be an able interviewer, albeit one who identifies very closely with her subjects and material. She is right to condemn the ways chastity organizations use sex to sell abstinence. Yet while she critiques their sexy campaigns, ultimately, she agrees with their underlying message. In doing so, she leaves unexamined many questions faced by evangelical teens seeking answers about sex.

Amy Frykholm is associate editor of The Christian Century. Her most recent book is See Me Naked: Stories of Exile in American Christianity.