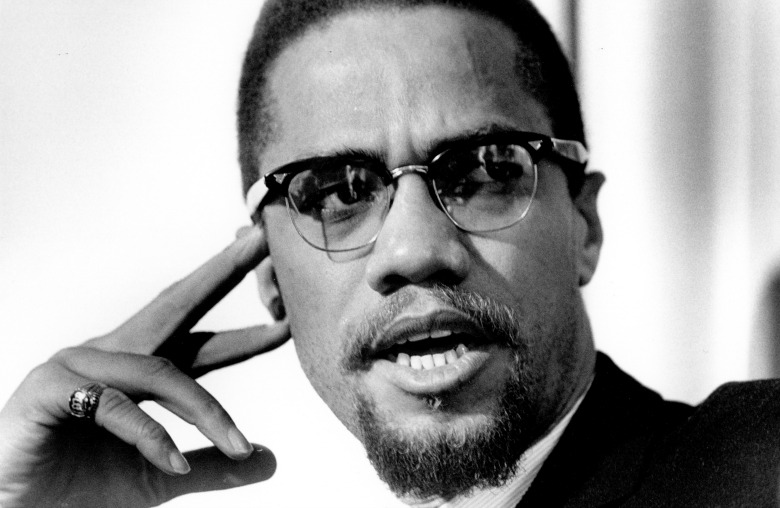

(Getty/Michael Ochs)

I fell in love with Malcolm when I was fifteen. He was eloquent, handsome and, most importantly, revolutionary. Among a litany of emotionally stunted fictional white men, the Caulfields and Gatsbys of the standard high school English syllabus, the central character in The Autobiography of Malcolm X stood apart. As the only Muslim in my English class, I was quietly convinced that I understood Malcolm in a way that no one else could.

As I approached Malcolm’s birthday this month on May 19, I reflected on why I was so quick to identify with his story as a teenager. I have not spent time in prison, I did not have an impoverished childhood, and I will never know the struggle of being African American in the United States. I remember being intrigued that his was not the Islam I saw caricatured by the media as I came of age post-9/11, nor was it the Islam of the foreign-born imams who I struggled to follow on the rare occasion that my dad took us to a mosque. To me, Malcolm X’s Islam was the unapologetic Islam of the streets. I was drawn to Malcolm because he was cool.

I was born to a second-generation Swedish American Lutheran mother and an immigrant Muslim Pakistani father. My mother did not want to convert, a decision my father respected, but she agreed to raise us as Muslims. Growing up in Brooklyn in what was then a black majority neighborhood, Islam acted as a passport of sorts—linking my visually out-of-place family to the Senegalese restaurant owner, the African American pharmacist who always closed for jummah (Friday prayers), and the Yemeni bodega owner. The local mosque issued the athan (call to prayer) four times a day, skipping only the predawn prayer out of respect for sleeping neighbors. Years later I was surprised by the controversy that followed Duke University’s attempt to issue the call to prayer from the campus’s chapel. Our neighborhood was by no means Muslim majority, but the significant Muslim presence made it clear that being Muslim was respected.

Post-Trump Islam is becoming an increasingly racialized category in the United States. “Punish a Muslim Day” took place this past April. The day originated in England with a widely circulated letter whose authorship remains unknown, which called for various attacks against Muslims including throwing acid on people’s faces and bombing mosques. A Pakistani American man tweeted in response:

On #PunishAMuslimDay. I don’t want to give such a vile idea the Twitter oxygen it craves. Just remember what our hero, martyr, and walī, Malcolm X said: “Be peaceful, be courteous, obey the law, respect everyone; but if someone puts his hand on you, send him to the cemetery.”

Clearly, I am not alone in my reverence for Malcolm X. My Facebook newsfeed is flooded every February on the commemoration of his assassination with images of Malcolm posted by South Asian Americans with captions like, “May Allah bless our hero.” (Full disclosure: I may have also posted an Instagram or two.) Young South Asian Muslims who embrace Malcolm as a walī, or saint-like figure, claim his narrative of counterculture and resistance as their own. This narrative is appealing because it is both authentically American and stands in rebellious contrast to the assimilationist aspirations of an older generation of South Asians.

Muslims are the most racially diverse religious group in America. According to the Pew Research Center, 41 percent of Muslims are white. (Pew follows the Census Bureau in coding Arabs and Persians as white, a categorization contested by many who argue that they are not perceived as white in America.) About 28 percent of Muslim Americans are Asians, a category predominantly made up of South Asian immigrants and their descendants from countries such as Pakistan, India, and Bangladesh. And, 20 percent of Muslim Americans are black, a category that includes African Americans, as well as recent African immigrants and their descendants from countries such as Senegal, Ghana, and Nigeria.

The average American thinks of Muslims as a brown mass, lumping together South Asians and Arabs, and ignoring black Muslims. The racialization of Islam has obscured both the diversity of Muslim America, and the tensions that accompany that diversity. These tensions, ranging from serious to light-hearted, played out in my own childhood experience. Back in Brooklyn, the Senegalese might look down upon the African American Muslims and incorrectly assume that they were recent converts. When my grandmother visited from Pakistan and prayed in the Shi’a manner to which she was accustomed, a board member from our local Sunni mosque brusquely suggested that we shift to a Shi’a establishment; we never went back again. My father had heard Arab men refer to each as habibi, or “dear.” In a cross-cultural faux pas, he used it trying to be friendly, but our Palestinian grocer did not take the term of endearment kindly.

Beyond my neighborhood, discrimination against black Muslims is rampant in Muslim American spaces. I was shocked to hear a Pakistani American classmate in my undergraduate Muslim Student Association refer to a Muslim international student from West Africa as a “black monkey” in Urdu. More than once I have heard my uncles wax angrily and poetically about their treatment in this country, only to slip in a veiled racist remark about African Americans a few moments later.

On a structural level, and looking specifically at South Asians, white converts and South Asians are vastly overrepresented among the leadership of prominent Muslim American institutions such as the Islamic Society of North America. In her book American Muslim Women, sociologist Jamillah Karim demonstrates the ways in which racially segregated divisions in housing between South Asians and African Americans in Chicago and Atlanta influence the racial demographics of mosques in those cities. Following the patterns of the neighborhoods they serve, mosques are often divided along racial lines, although it’s worth noting that American mosques are typically more racially integrated than American churches.

What is the source of South Asian racism against black Muslims? As a result of the history of race in the United States and the ongoing prevalence of a black-white racial binary in which whiteness is associated with goodness, the process of immigrants assimilating and aspiring to the American dream of a secure middle-class life often ends up translating into aspiring to whiteness. South Asian American communities are no exception. Furthermore, colorism is a huge issue in South Asia, where whiteness is often equated with beauty.

In light of this history, is it a revolutionary act for young South Asians to embrace Malcolm X? It can be, but unfortunately, this embrace often falls into the trap of removing Malcolm from his historical context and flattening his legacy. For example, Malcolm’s continued focused commitment to black liberation post-hajj is often muted in South Asian-sanctified visions of Malcolm. The same Muslims who sanctify Malcolm X often dismiss African American Muslims, associating them with the Nation of Islam (NOI). There has been a lot of debate in the press recently about Louis Farrakhan, the current leader of the Nation of Islam, and his anti-Semitic remarks. Farrakhan’s remarks should be analyzed and held up to scrutiny, but it’s also important not to overstate his influence. The Pew Research Center points out: “Perhaps the best-known group of black Muslims in the U.S. is the Nation of Islam.” But today only 3 percent of black Muslims are part of the Nation of Islam. The vast majority of the NOI’s former adherents followed Warith Deen Mohammed’s leadership and converted to Sunni Islam in the late 1970s.

It should come as no surprise that Muslims Americans have a race problem; after all, what is more authentically American than non-black people profiting from aesthetic expressions of blackness while ignoring actual black communities? In Muslim Cool: Race, Religion, and Hip Hop in the United States, Su’ad Abdul Khabeer describes the aura of cool that has come to be associated with black Muslims, especially as expressed through hip hop culture. Many young Muslims of all ethnicities draw from Muslim cool, and Khabeer details the irony of upper-class Pakistani American kids in the southern suburbs of Chicago flaunting hip-hop culture and benefiting from the aesthetics of black Muslim cool, while having no connection whatsoever to the actual black Muslims living mere miles away.

South Asians are not unique in their reinvention of Malcolm as a saint; in fact, they are building upon a much longer history of commodifying Malcolm which Manning Marble, the formidable historian and expert on Malcolm, details in his article, “Rediscovering Malcolm: A Historian’s Adventure in Living History.” The hip-hop generation first revived Malcolm’s legacy in the 1980s. Artists such as Tupac Shakur and Public Enemy referenced Malcolm and even sampled excerpts from his speeches. In 1992, the year I was born, Spike Lee released the film “X.” In the 1990s President Bill Clinton, whose policies on crime increased mass incarceration at an unprecedented rate, was spotted wearing a Malcolm X t-shirt while jogging outside the White House. Most ironically of all, the United States government, which had the FBI patently ignore and even encourage death threats against Malcolm while infiltrating every organization that he founded or was associated with, issued a postage stamp of Malcom in 1999.

Movements such as the Nation of Islam are often portrayed as historically disconnected from other forms of Islamic expression in the United States, when in fact Malcolm X was an international Muslim American spokesperson during his lifetime, and the NOI provided Malcolm a platform for the majority of his career. The politics of the Nation shifted with time, but it was responsible for introducing thousands of Americans to Islam. Until recently, scholars across many academic fields have contributed to the erasure of black Muslims by frequently relegating the black Muslim American experience to a quirky sociological footnote. The field of American Islam is growing, but many university departments across the country are still structured to view Islam as the province of the exotic orient and not as part of American life. Even ethnographic work on American Muslims tends to focus on immigrant, mosque-affiliated American Muslims. There is nothing wrong with these portrayals, but their ubiquity gives a very limited picture of Muslim America’s diversity.

In Muslims and the Making of America, Amir Hussain, a theological studies professor at Loyola Marymount, gives ample examples of black Muslim luminaries, including of course, Malcolm X. The short text is clearly meant to be accessible and shift public perceptions of Islam, which is a noble goal. But I was troubled to read this line in the introduction: “We were here before America was America, arriving in slave ships bound for the colonies.” Who is we? Hussain is a Pakistani American man raised in Canada. His ancestors were not forcibly taken on slave ships to the United States, and his everyday lived experiences are not the same as someone who is perceived by society as a black American.

I have no doubt that Hussain’s invocation of “we” came from a place of goodwill and a desire to shed light on the diversity of Muslim Americans stories. However, there is a difference between standing in solidarity and learning from someone’s liberation struggle and appropriating that struggle. Fighting Islamophobia should not come at the cost of ignoring discrimination within our communities.

In the face of rising anti-Muslim sentiments, South Asians and Muslims of all backgrounds can learn from Malcolm X and draw upon his message of self-love and communal self-determinism. But for non-black Muslims to truly honor Malcolm, they must also call out racism internal to Muslim American communities and be honest that the cool that Malcolm demonstrated was a response to the circumstances that he faced, and those circumstances are not ours.

Yasmine Flodin-Ali is a Ph.D. student in Islamic Studies at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, where she studies issues of race and gender in contemporary Muslim American communities.