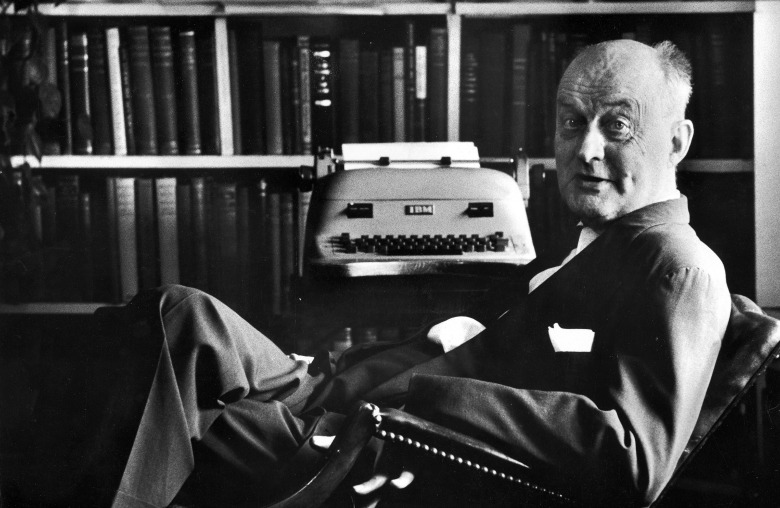

(Getty/Alfred Eisenstaedt/LIFE)

Reinhold Niebuhr, it seems, is everyone’s favorite theologian. Then-candidate Barack Obama told David Brooks in 2007 that Niebuhr was one of his “favorite philosophers.” There is “serious evil in the world, and hardship and pain,” Obama said. “And we should be humble and modest in our belief we can eliminate those things. But we shouldn’t use that as an excuse for cynicism and inaction.”

President Jimmy Carter said, “Niebuhr was always present in my mind in a very practical way, particularly when I became President and was facing the constant threat of a nuclear war, which would have destroyed the world.” In his 2007 book, John McCain dedicated a chapter to Niebuhr. And presidents and senators are not alone. Since the conservative columnist David Brooks wrote in 2002 that “I’m amazed that Reinhold Niebuhr hasn’t made a comeback since September 11,” Niebuhr has experienced a revival among theologians, historians, public commentators, and politicians.

A new documentary called An American Conscience: The Reinhold Niebuhr Story, tries to capture and explain why Niebuhr is experiencing something of a renaissance. It is directed by Martin Doblmeier, who has worked on dozens of faith-based films. (The John C. Danforth Center at Washington University in St. Louis, which publishes this journal, co-hosted a screening of the film in March.) “The questions Niebuhr raised in his time,” Doblmeier said in an interview with The Christian Post, “are all themes that seem in the forefront for many Americans today and Niebuhr is an insightful companion for those kinds of reflections.”

Reinhold Niebuhr was a theologian of the nuclear age. He became a public intellectual after the United States dropped two atomic bombs on Japan at the end of World War II. To a country run by mainline Protestants, who had long ago abandoned Armageddon, rapture, and the end times, Niebuhr needed them to believe that the end was possible, and perhaps probable. By the early 1940s Niebuhr was well-known among theologians as a professor at New York’s Union Theological Seminary who published largely in the Christian press. By 1948 he was on the cover of Time magazine, which promoted him as a figure who could help Americans understand the new predicaments they faced. Hiroshima created a world suitable for Niebuhr’s theological grand drama and launched him to fame.

Sin, irony, tragedy. These words leapt out of the pages of Niebuhr’s books and speeches. Humanity was fallen and redeemed through God’s grace, Niebuhr wrote. But that redemption is always incomplete and we can never rise to the standards set forth in the Bible. Only by accepting our limitations could we make the best out of an imperfect situation. In a world full of evil, we must choose good, but we must accept that we can never get rid of sin entirely. The irony of our situation is that we must often do what is considered evil for the sake of good.

Jimmy Carter could quote by heart from Niebuhr’s 1932 book Moral Man and Immoral Society. It contained what many believe is one of Niebuhr’s most important insights: Individuals were capable of overcoming sin, he argued, but groups were not. “Individual men may be moral” because they “are endowed by nature with a measure of sympathy and consideration for their kind,” Niebuhr wrote. But to empathize with others is “more difficult, if not impossible, for human societies and social groups.” Man could become moral but he was always destined to live in an immoral society.

With this book Niebuhr parted ways with his pacifist past. As Cornel West says in An American Conscience, “Part of the greatness of Reinhold Niebuhr is that he was willing to risk his popularity in the name of integrity.” When pacifists took exception to Niebuhr’s use of Christianity to endorse violence, “he had to engage them and tell them I have changed my mind owing to these kind of arguments and insights that I have learned.”

Niebuhr’s debates were never this civil. A reviewer wrote in 1933 of Moral Man and Immoral Society, “To call this book fully Christian in tone is to travesty the heart of Jesus’ message to the world.” The reviewer took issue with the text because Niebuhr implied that Christians must sometimes resort to violence when dealing with groups. Niebuhr traded barbs with pacifists for the rest of the decade. “If modern churches were to symbolize their true faith,” he wrote in 1940, “they would take the crucifix from their altars and substitute the three little monkeys who counsel men to ‘speak no evil, hear no evil, see no evil.”

The lead-up to World War II thrust Niebuhr into the spotlight. His calls to understand power—which historian K. Healan Gaston identifies in the film as his “major preoccupation of his thought and his primary legacy”—were prophetic calls to his fellow Americans in 1939 and 1940 to join the war effort against Nazi Germany and Japan. In his view the aggressive fascist powers stood on one side. On the other were the naïve pacifists who would refuse to fight evil. We must choose the sensible middle ground, he argued. We must do evil for the sake of the good.

Events turned his way. With American entry into the war, Niebuhr’s pacifist critics were largely silenced. Niebuhr had effectively created a just war theory for a religion that had none. Or, as historian David Hollinger puts it, “Reinhold Niebuhr made war safe for American Protestants.” In the process, he silenced some of the most trenchant critics of American power.

But these critics had prophetic qualities of their own. Pacifists A. J. Muste and John Haynes Holmes Jr. warned that installing military bases around the world would pull Americans into one war after another. They called on America to give up its empire. They counseled that conscription would militarize domestic life. But very few people listened. Niebuhr’s “realist” theology became the new Cold War orthodoxy.

By 1952, Niebuhr had become a celebrated Cold Warrior, who was invited to State Department meetings to advise America’s mandarins to act wisely and humbly in their fight against the Soviet Union. That year, he wrote one of Barack Obama’s favorite books, The Irony of American History. That book repeated the earlier warnings about the imperfectability of society, but now he was writing about American foreign policy. The world was an imperfect place, and Americans had to shed their innocence if they were to act wisely in their fight against the Soviet Union. Stay firm against the communist threat, Niebuhr counselled, but do not succumb to arrogance or crusading.

This transcendent Niebuhr—speaking beyond his time to our own—appears in the recollections of the many figures interviewed in An American Conscience. But to his contemporaries he sounded differently. In 1952, in the middle of the Korean War, nobody really needed to be convinced that the United States must take responsibility in the world. Niebuhr cautioned against crusading, but the United States was doing just that. And in putting a theological stamp of approval on the Cold War, Niebuhr was endorsing as a responsible middle ground the very fanaticism he was warning against.

In other words, Niebuhr was not speaking truth to power. He was reassuring the powerful that they were on the right side of history. The most uncharitable criticism in this vein came from Noam Chomsky. He called Niebuhr’s ideas “soothing doctrines for those preparing to ‘face the responsibilities of power,’ or in plain English, to set forth on a life of crime.” Niebuhr’s ideas were more than this, of course. Niebuhr continues to inspire reflection by some of today’s most astute critics of American power, like Andrew Bacevich and Cornel West. But biographer Richard Fox got it right that Niebuhr helped America’s Cold Warriors “maintain faith in themselves as political actors in a troubled—what he termed a sinful—world. Stakes were high, enemies were wily, responsibility meant taking risks. Niebuhr taught that moral men had to play hardball.”

Niebuhr’s popularity began to wane in the 1960s and 1970s. Liberation theology overtook Niebuhr’s Christian realism in seminaries, while popular commentators became suspicious of endorsements of America’s military muscle at a moment when it was being flexed in Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos. Millions of mainline Protestants stopped going to church while evangelicals cared little for Niebuhr’s liberal theology. Niebuhr was losing his audience.

By the 1980s, academics—who had never taken Niebuhr seriously—deconstructed the very foundations of Niebuhrian thought. Niebuhr spoke of the sinful nature of man. But academics showed that “human nature” was a fiction. The world is radically pluralistic. There is no singular, universal person but a variety of people divided by culture, nationality, and gender. And what seems natural to us is usually “constructed” through historical and political forces, often times for nefarious ends. Niebuhr’s ideas started to seem misguided at best.

It took the tragic events of September 11, 2001, to revive Niebuhr. Sin, irony, and tragedy had returned to the American vocabulary. Those fighting the war on terror—Obama the most famous among them—turned to Niebuhr. But Niebuhr’s revival begs the question: Why does a theologian who reached the height of his popularity in the atomic age speak clearly to so many in the age of terror?

“If we’re looking for a thread that unites almost all of our interviewees, they’re all working with some form of power or influence,” said Jeremy Sabella, who is the author of a companion book to An American Conscience. “They’re all trading in a certain type of power and influence. And Niebuhr is excellent on helping people think through the predicaments of working with that power and influence as badly flawed human beings who struggle with sin.”

One of those powerful people is FBI Director James Comey, who likely used the pseudonym “Reinhold Niebuhr” on his Instagram and Twitter. Comey had written his undergraduate thesis on Niebuhr’s call to public action in 1982. “Niebuhr’s book Moral Man and Immoral Society says it’s not enough to sit in an ivory tower,” Comey later reflected about his decision to go into law enforcement in an interview with New York magazine. Referencing his son’s death, 9/11, and the Holocaust, Comey asserted that “it is our obligation as people not to let evil hold the field. Not to let bad win.”

Comey became the U.S. attorney in New York City in January 2002, just months after the tragedy of September 11, 2001. He argued that Jose Padilla, who was accused of planning to set off a dirty bomb in New York, had no right to a defense lawyer. Padilla, a natural-born American citizen, spent three and a half years in a military prison as an enemy combatant. In 2004 Comey became assistant attorney general in the Bush administration and signed off on the CIA’s use of waterboarding and other forms of torture. In his role as director of the FBI, he has been in charge of programs that surveil Muslim Americans, prosecute domestic terrorism, and prevent would-be terrorists from infiltrating the United States.

Do Comey, Obama, and other powerful people read Niebuhr because he tells them to act with humility and caution? Or is it because Niebuhr tells them that moral men have to play hardball? The most likely answer is both, and we should find that more than a little troubling.

Gene Zubovich is a postdoctoral fellow at the John C. Danforth Center on Religion and Politics. Follow him @genezubovich.