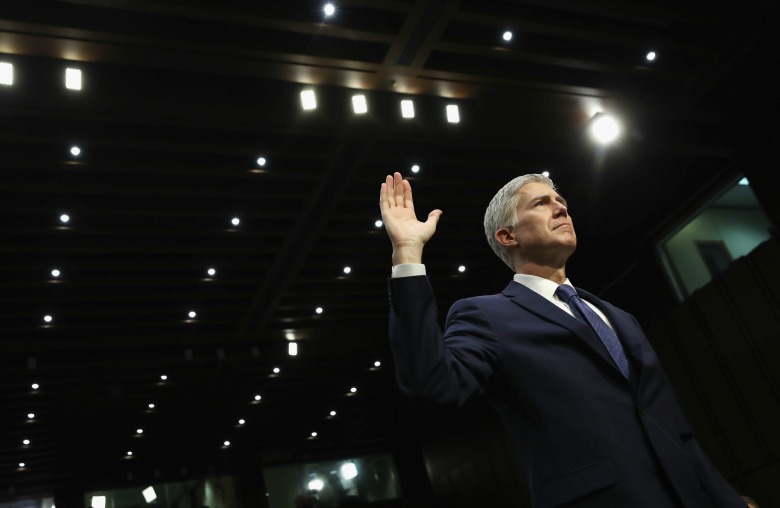

(Justin Sullivan/Getty)

A little over a year ago, Associate Justice Antonin Scalia died. Justice Scalia was among the most consequential jurists in American history. For many traditional religious believers, mainstream Republicans, and conservative intellectuals, the Supreme Court vacancy created by Scalia’s death was an important—perhaps the strongest—reason to vote for Donald J. Trump in the recent election. And, for those to whom the balance and future of the Court mattered greatly, questions about religious freedom, church-state relations, and the role of religious believers and institutions in the public square loomed particularly large.

This was not because Scalia wrote a large number of controlling or influential majority opinions in cases involving the First Amendment’s Religion Clause. In fact, he wrote only one (a landmark, to be sure, but still only one): In a 1990 case, Employment Division v. Smith, Scalia announced for a Court majority that the First Amendment’s Free Exercise Clause does not require exemptions from “neutral” and “generally applicable laws” that burden the exercise of religion. This ruling prompted criticism on both sides of the congressional aisle and across the political spectrum and eventually resulted in the near-unanimous passage of the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA) of 1993. Still, through dozens of memorable, sometimes bracing, concurring and dissenting opinions, Scalia shaped and even drove the conversation.

President Donald Trump has nominated Judge Neil M. Gorsuch of the United States Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit to replace Scalia. The hearings in the United States Senate’s Judiciary Committee started this week, and it already seems clear that they will involve more scripted posturing and predictable campaigning than thoughtful examination or insightful questioning. For weeks, the usual activists have been doing the usual name-calling and sky-fall predicting, and Gorsuch has performed the pre-hearing rituals of completing War and Peace-length questionnaires and dutifully calling on senators who will pretend to expect him to answer questions about whether he would vote to overrule Roe v. Wade or Citizens United.

It is entirely clear and no serious person denies that Gorsuch is well qualified to serve on the Court. His credentials are sparkling, his reputation for collegiality and civility is excellent, and his writing is both engaging and clear. It is true that he is being opposed by some partisans, commentators, and academics, but this opposition reflects disappointment over the election results, policy disagreements with the outcomes in some of Gorsuch’s opinions, and resentment over the Republicans’ blocking of President Obama’s (also well qualified) nominee, Judge Merrick Garland—not Gorsuch’s merits. His critics will lob the usual adjectives—“dangerous,” “disturbing,” “reactionary,” “extreme,” and so on—but they won’t, and we shouldn’t, think they actually apply. Were our politics not dysfunctional, he would be confirmed—as Scalia was—unanimously.

What would the confirmation of Gorsuch to the Supreme Court of the United States mean for the First Amendment and for religious-freedom-under-law? This is, to put it mildly, an interesting time when it comes to these matters. The so-called “culture wars” do not seem to be abating, conventional religious observance and affiliation appears to be declining, and the nature—even the value—of religious liberty seems increasingly contested. Not long ago, President Clinton called religious freedom our “first freedom”; today, our leading newspapers tend to put it in scare-quotes.

It is tempting, and not entirely wrong, to answer the question with “not much.” After all, the confirmation of Gorsuch would not change the Court’s 5-4 partisan “balance” and it is reasonable to assume that a Justice Gorsuch would think about First Amendment and religious-liberty questions more like, say, Chief Justice John Roberts does than like, say, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg does. It is fair to say that, if Gorsuch is confirmed, the “big story” in law-and-religion is the significant shift that was avoided and not the one to come.

It is also important—and, maybe, reassuring—to remember that there is a solid consensus among the Roberts Court justices on some significant religious-liberty questions. Not every case is a 5-4, Republicans v. Democrats affair. Most cases are not Hobby Lobby. For example, in both the 2006 O Centro case and the 2015 Holt v. Hobbs ruling, the Court was both unanimous and generous in ruling for the claimant seeking an accommodation for religiously mandated practices. (Another accommodations case, EEOC v. Abercrombie & Fitch, was 8-1).

In the United States, the law of religious freedom and church-state relations can be imperfectly, but still usefully, divided into four categories. First, there are the cases about money and other forms of support for the educational, healthcare, social service, and other “secular” activities of religious schools, universities, hospitals, and charities. From the late 1960s through the mid-1980s, relying on an inaccurate understanding of Madison, Jefferson, and the Founding Fathers, the Court often treated such support as an unconstitutional “establishment” of religion and as a violation of the “separation of church and state.” In recent years, though, the tendency has been to allow such funding, so long as the programs and funding mechanisms are “neutral.” This is a welcome development.

Scalia was entirely on board with this movement away from discrimination in the doctrine, and it is reasonable to think that a justice appointed by President Clinton would have been more skeptical about, for example, educational-scholarship programs that help low-income children attend private and religious schools. Gorsuch has not written opinions that fall into this category but it seems likely, given all the givens, that he would agree with the other Republican appointees on the Court that this kind of cooperation, in the pursuit of appropriate government goals, is constitutionally permissible.

The second category of cases involves objections by religious believers to laws that, in their view, burden their “free exercise of religion.” The question here is whether the First Amendment’s “Free Exercise Clause” or some other religious-liberty statute requires the government to accommodate these objectors and to exempt them from the law’s burdensome requirements. The Court has changed course on this question several times over the last 50 years, but the rule now is that such exemptions are not required by the Constitution. They are, however, usually allowed, and so legislatures are generally permitted to remove such burdens, and accommodate religious objectors, if they want to.

A prominent example of such an accommodation, of course, is the federal Religious Freedom Restoration Act, which the Court applied in the Hobby Lobby case, but there are many others. Sometimes these exemptions are categorical, other times they call for a balancing of the government’s interests, on the one hand, and the burdens on religious exercise, on the other. Some of Gorsuch’s critics have focused on his opinions in this area. In the Tenth Circuit, in both the 2013 Hobby Lobby case and the 2015 Little Sisters of the Poor litigation, Gorsuch voted in favor of the religious claimants and for accommodation. In other decisions, he protected the religious-freedom interests of Native Americans and Muslims. Contrary to what some critical opinion writers have claimed, his votes and opinions did not give a blank check or absolute opt-out right to religious believers. Nor did he ignore the need to consider the costs to third-parties or the government of accommodation. In fact, he simply took seriously the religious-freedom statute enacted overwhelmingly by Congress, which directs the federal government to accommodate religious minorities and facilitate religious exercise to the extent possible.

In the coming years, there will be controversial clashes between some anti-discrimination laws and medical-procedure mandates, on the one hand, and sincere religious objections, on the other. Gorsuch’s record suggests that he will take seriously both the burdens that facially neutral laws can impose on religious believers and the requirement that the federal government do what it can to ease those burdens.

The third category of cases—and it is a big one—involves religious symbols and speech by public officials or in the public square. Think, for example, of the famous school-prayer decisions, or the annual Holiday Season ritual of lawsuits over Nativity scenes and menorahs on government property, or the Supreme Court’s recent decision involving the practice of a small town in New York of opening its town council meetings with a prayer offered by a local minister. These cases are very fact-specific and context-sensitive. They come out, frankly, all over the map (and Gorsuch has noted as much). Perhaps the best one can do is to say that religious symbols and speech are unconstitutional when they are seen as “coercive” or as “endorsing” religious faith; they are usually permissible when they merely involve traditional, ceremonial practices like “God save this honorable Court”; and they are constitutionally protected, even on public property, when they are the expression of private parties.

Here too, Gorsuch has a record. He has been respectfully critical—and compelling in his criticism—of the Court’s failure to provide consistent and clear guidance to lower courts, to local governments, and to citizens. In cases involving Ten Commandments displays and roadside crosses, he has recognized and respected the fact that there has always been a place in America’s public, civic life for religious symbols and speech. He appreciates that not every acknowledgement of religion is an unconstitutional religious establishment and that not all encounters with religious symbols or monuments in public are coercive or oppressive. If confirmed, he could help move the law away from an excessively subjective, unpredictable approach that depends too much on judges’ speculation about psychological states and décor-related minutiae. We should hope that he and his colleagues would step back, and leave to political processes and local conversations the tricky decisions about what civic friendship in a pluralistic society requires when it comes to holiday displays, school pageants, and the like.

The fourth and final category is a bit of a grab-bag. It includes cases and controversies that have to do with government “entanglement” in matters of religious doctrine and church discipline. Famous cases in this category involve political interference in intra-religious disputes or inappropriate deference by government to religious authorities in secular matters. The most important recent case in this category is probably the Court’s 2012 Hosanna-Tabor decision, in which the Court—unanimously—confirmed that the secular anti-discrimination laws cannot be used to overturn decisions about hiring and firing religious ministers and teachers. Still, this ruling left a lot of questions unanswered, and a lot of room for doctrinal development. Gorsuch does not have a record in this area, but it seems likely that he will appreciate the very deep historical roots of the Court’s reluctance to allow secular authorities to decide religious questions.

Religious freedom is, still, our “first freedom.” If our most sacred things are not free, then nothing else that matters is, either. A government that imagines itself competent to re-arrange or supervise our beliefs about the transcendent is certainly not to be trusted when it comes to respecting our privacy or property. Religious liberty is not special pleading, and it is not a luxury good. It is foundational to our constitutional order and democratic aspirations. The Supreme Court can safeguard religious freedom, for everyone, but it matters at least as much that a commitment to human dignity is deeply rooted in politics, legislatures, and neighborhoods. Judge Neil Gorsuch’s record suggests that he understands this.

Richard W. Garnett is the Paul J. Schierl/Fort Howard Corporation Professor of Law at the University of Notre Dame.