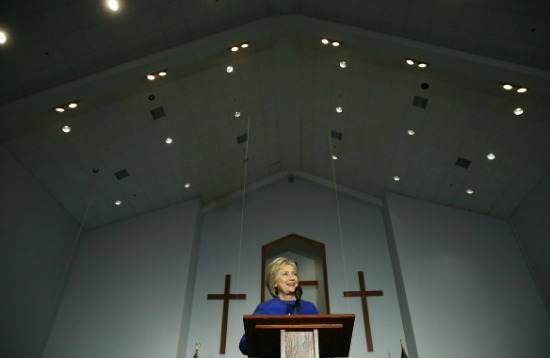

(Getty/Win McNamee)

Last month, at a closed meeting with evangelical leaders, Donald Trump asserted his Christian bona fides. He boasted of his child-rearing practices, touted the virtues of Sunday School, identified religious liberty as “the number one question,” promised to appoint anti-abortion Supreme Court justices, and assured those gathered that if he were to be elected, people would be saying “Merry Christmas” again.

Trump also took the opportunity to question his opponent’s faith. Hillary Clinton, he claimed, had “been in the public eye for years and years,” and yet “we don’t know anything about Hillary in terms of religion.”

This, of course, is utter nonsense.

Although Clinton has confessed a certain reticence when it comes to “advertising” her faith, and a preference for “walking the walk” rather than risk trivializing “what has been an extraordinary sense of support and possibility” throughout her life, she has consistently testified to her Methodist faith over the course of her long career in politics.

Skeptics may be surprised to learn that Clinton taught Sunday school and delivered guest sermons on Methodism as first lady of Arkansas, and that she devoted an entire chapter of her first book, It Takes a Village, to the importance of faith. They may not know that in her memoir Hard Choices, she credits the Wesleyan mantra, “Do all the good you can, at all the times you can, to all the people you can, as long as ever you can,” with prompting her to enter electoral politics, and later to leave the Senate and accept President-Elect Obama’s invitation to become secretary of state. In short, Clinton depicts her entire career in public service as a means of putting her faith into action.

Careful observers have long connected Clinton’s progressive politics to her Methodist faith. In his 1993 profile of the then-First Lady, Michael Kelly noted that her liberalism was derived from her religiosity; her politics combined “a generally ‘progressive’ social agenda with a strong dose of moralism, the admixture of the two driven by an abundant faith in the capacity of the human intellect and the redeeming power of love.”

Clinton had imbibed this mix of Methodist moralism and social activism from her earliest years. Her mother Dorothy, who had survived a harrowing childhood before ending up an upper-middle-class housewife in suburban Park Ridge, Illinois, never lost her compassion for those less fortunate. A closet Democrat, she embraced a social gospel Methodism attentive to the needs of “the least of these.” In this she was not alone. The women of Park Ridge Methodist lived out their faith, raising funds for charity, ministering to migrant workers, and addressing issues of racial and global injustice.

Clinton’s own commitment to an activist faith was solidified under the tutelage of the Rev. Don Jones, a dashing youth minister who arrived in Park Ridge in the fall of 1961. In a 2014 speech to a gathering of United Methodist Women, Clinton recalled how Jones “went out of his way to open our eyes to injustice in the wider world” beyond their “sheltered, middle-class, all white community.” He brought his young charges to hear Martin Luther King, Jr., and to visit Black and Hispanic young people in inner-city Chicago churches. And he introduced the precocious teenager to the writings of Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Reinhold Niebuhr, and Paul Tillich. “Bonhoeffer stressed that the role of a Christian was a moral one of total engagement in the world,” Clinton later recollected in Living History, while “Niebuhr struck a persuasive balance between a clear-eyed realism about human nature and an unrelenting passion for justice and social reform.” Tillich wrote of sin and grace existing in constant interplay, and he articulated a “crisis of meaning,” themes Clinton would return to at critical moments in her life.

When Clinton left Park Ridge to attend Wellesley College in the fall of 1965, she stayed in close contact with Jones, and she brought with her a subscription to motive magazine, a publication of the Methodist Student Movement she had received from her church. As first lady, Clinton shared that she had kept each issue of motive she had received, to that day.

Not long after arriving at Wellesley, Clinton assumed leadership of the Young Republicans. But over the coming months her political commitments began to shift. By 1968 the former Goldwater Girl was campaigning for anti-war Democrat Eugene McCarthy, and she credits motive with helping nudge her away from the Republican Party.

How did a religious magazine reorient Clinton’s politics? Her college years spanned one of the most momentous eras in twentieth-century American history. The escalation of the war in Vietnam, the prophetic challenge of the Civil Rights movement, and the growing alienation of the student generation threw into question dominant Cold War narratives and the white, middle-class status quo. Each month Clinton encountered articles contesting the received wisdom of her sheltered upbringing, but written from a religious standpoint that resonated with her own Methodist faith. Writers in motive eloquently depicted Civil Rights as a moral and spiritual cause, connected Civil Rights at home to liberation movements abroad, and condemned the war in Vietnam and the actions of the U.S. government around the globe. The magazine also rejected the emerging Religious Right’s characterization of America as a “Christian nation,” a notion they considered idolatrous and an expression of sinful pride.

In this way, motive assisted Clinton in articulating a political identity that increasingly aligned with the Democratic Party, and one consistent with her core religious commitments.

While she attended Yale Law School, Clinton’s social gospel Methodism continued to mold her politics as well as her career choices. Her former youth minister later identified to NPR “a continuing thread through her life about caring for the poor, for the disadvantaged, and her attempt to play a role in achieving social justice.” Her work for the Children’s Defense Fund right out of law school, her efforts to reform public education as first lady of Arkansas, and her eagerness to tackle health care reform upon arriving in Washington can all be seen as expressions of her religiously inspired mission to make the world a better place.

Yet this sense of mission was not without its downsides. Even Jones noted wryly in Newsweek that Methodists not only like to do good, but they like to think they know what’s good for other people. And critics have suggested that Clinton’s sense of moral mission might be the source of her occasional unwillingness to compromise, as evidenced perhaps most painfully in the failure of her health care initiative.

It would be wrong, however, to see Clinton’s faith merely as the source of her liberal politics. A closer look at her religious commitments reveals a more complex range of beliefs that have found expression in conflicting and sometimes surprising ways.

Growing up in Park Ridge, Clinton was not only shaped by her mother’s social gospel Methodism, but also by a more conservative expression of the faith espoused by her father. In Clinton’s depiction, Hugh Rodham was a “self-made” businessman and a “rough, gruff” Republican who traced his family’s religious heritage back to the Wesley brothers themselves, and who championed a faith that privileged self-reliance, conservative values, and Cold War politics. Clinton recalled how she struggled as a child “to reconcile my father’s insistence on self-reliance and independence and my mother’s concerns about social justice and compassion.” In many ways, she has continued to wrestle with this question throughout her adult life.

Even as her youth pastor was offering her a “liberalizing” vision of “faith in action,” another member of her church was casting a very different vision. Paul Carlson, who was also her ninth-grade history teacher, kept his students on edge with stories of Communist oppression, reinforcing Clinton’s already strong anti-communist propensities. Jones later acknowledged that he and Carlson (whom Jones characterized to author Gail Sheehy as “to the right of the John Birchers”) were “fighting for her soul and her mind.”

Clinton later reflected in Living History that the disagreement between the two men was “an early indication of the cultural, political, and religious fault lines that developed across America” over the past half century. At first glance it appears that Jones won the battle. Yet surprisingly, Clinton insisted that she “did not see their beliefs as diametrically opposed then or now.”

Perhaps that is because, as Kathryn Joyce and Jeff Sharlet argued in a piece for Mother Jones, Clinton’s religious education wasn’t as liberal as is often perceived. Jones himself was no radical; his theology was neo-orthodox, “guided by the belief that social change should come about slowly and without radical activism.” Like many of the writers in motive who called for a new articulation of the Christian faith, Jones sought “a third way,” an alternative to fundamentalism and liberalism, to the politics of the Old Left and the New Right.

The Niebuhr that Clinton encountered, according to Jones, was a cold warrior who had come to doubt his earlier commitment to progressivism. Tillich, too, cautioned against an overemphasis on social activism to the neglect of personal redemption. In fact, Joyce and Sharlet contend that “Niebuhr and Tillich’s combination of aggressiveness in foreign affairs and limited domestic ambition naturally led Clinton toward the GOP.”

As a college student, Clinton struggled to reconcile competing visions of the good—to bring together her intellectual realism with her spiritual compassion. In his biography of her, Carl Bernstein notes that Clinton pondered in a letter to her former youth pastor whether it was indeed possible to be “a mind conservative and a heart liberal.” Bernstein suggests that no phrase more aptly describes Clinton than this seeming paradox.

Although considered a liberal Christian by many conservatives (to say nothing of those who refuse to concede that she is in fact a Christian), Clinton has forged closer ties with conservative evangelicalism than is often assumed. When Clinton arrived in Washington, she joined a women’s Bible study and prayer group that was part of the Fellowship, an exclusive group populated by Christian power-brokers who believed they enjoyed a special calling to do God’s will.

As first lady, she read Christianity Today and writings by evangelical pastors Tony Campolo and Gordon MacDonald, as well as by Catholic priest Henri Nouwen. She voiced concern that the United Methodist Church might have become “too involved in the social gospel,” at the cost of paying “enough attention to questions of personal salvation and individual faith.” And she expressed sympathy for evangelicals and fundamentalists who were unfairly stereotyped by the media, affirming their theological striving to make sense of their lives and the world around them.

The influence of Clinton’s faith on her politics is also more nuanced than is often appreciated. As senator, she became part of the Senate Prayer Breakfast, which led to unlikely alliances with conservative Republicans on issues ranging from human trafficking to religious freedom. And on a range of other issues, from her support for the Defense of Marriage Act to her vote on the Iraq War, her politics parted ways with the more progressive voices both in her party and in her church.

In 2014, in an interview with The New York Times Sunday Book Review, she recommended E. J. Dionne’s Our Divided Political Heart, because it “shows how most everybody has some conservative and liberal impulses, but just as individuals have to reconcile them within ourselves, so does our political system if we expect to function productively.” Her adolescent attempt to reconcile head and heart, conservativism and liberalism, has turned into a life-long quest.

Clinton’s faith has inspired her liberal politics as well as her conservative tendencies. But perhaps the most intriguing and least understood aspect of her faith has been her unrelenting search for a deeper sense of meaning.

As a high school student Clinton confronted questions of meaning and alienation through the writings of Tillich. In college she struggled to discern her own identity and purpose. In her much heralded 1969 commencement address at her alma mater, she spoke of the emptiness of the “prevailing, acquisitive, and competitive corporate life,” of her generation’s desire for “freedom from the burden of inauthentic reality,” of the need to come to grasp “with some of the inarticulate maybe even inarticulable things that we’re feeling.”

As first lady, Clinton again attempted to articulate the inarticulable. It was the spring of 1993, health care reform was coming undone, her financial practices were under investigation, and her father had just been taken off life support. In a moment of unguarded reflection, she delivered an unscripted address in Austin, Texas, calling for a “new politics of meaning.” She told the audience, “Somehow economic growth and prosperity, political democracy and freedom are not enough.” In order to address the lack of individual and collective meaning that plagued the nation, Clinton believed it necessary “to break through the old thinking that has too long captured us politically and institutionally,” to reject ideological polarization that sought salvation in the market economy or in big government. Instead, she called for “a new ethos of individual responsibility and caring,” for the need to recognize that “we are all part of something bigger than ourselves.”

At the time, Clinton’s speech failed to inspire. Major news outlets lampooned her “psychobabble.” Ongoing investigations into her own financial dealings certainly didn’t help her case, nor did the fact that those on the left had largely ceded talk of virtues and values to the Religious Right. And Clinton herself conceded that she was up against the limits of her vocabulary in her attempt to address questions of this magnitude.

Clinton was chastened by this ridicule (which undoubtedly contributed to her reticence to discuss her faith in public). But in recent months, echoes of this spiritual quest have once again been finding their way into Clinton’s speeches. In the face of Trump’s divisive rhetoric, and in the aftermath of the shootings in Louisiana, Minnesota, and Texas, Clinton has called for more “love and kindness,” for Americans to come together, to find common ground, to listen to each other, and “to do some hard work inside ourselves, too.” Earlier this month, she ended a speech with a favorite Bible verse, reciting it to members of the AME Church: “Let us not grow weary in doing good, for in due season we shall reap if we do not lose heart.”

It remains to be seen whether her words will resonate in our current era of political, social, and perhaps also spiritual crisis, and whether she has the moral authority, the political capital, or the vocabulary to cast a vision that can bridge the divides that have brought the nation to a place of collective soul-searching. But her attempts to do so should not be dismissed as evidence of flip-flopping or political pandering. As her religious history makes clear, she has long sought to reconcile the values of the left and the right, to call for a more compassionate politics, and to do so from a place of faith.

Kristin Du Mez is chair of the history department at Calvin College. She is author of A New Gospel for Women: Katharine Bushnell and the Challenge of Christian Feminism, and is currently writing a religious history of Hillary Rodham Clinton.