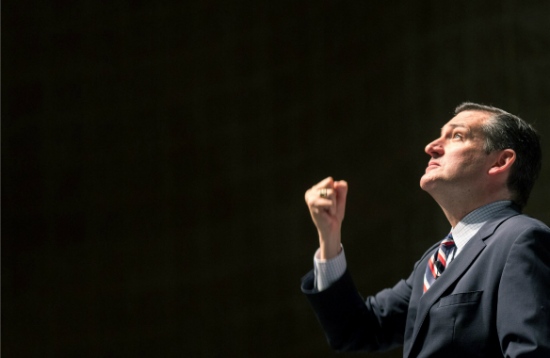

(Getty/Richard Ellis)

By almost any reckoning, Ted Cruz’s campaign for the Republican presidential nomination presents voters with a paradox—several paradoxes, actually. The senator from Texas styles himself a populist, and yet nearly everyone who knows him well detests him. At this writing, only two of his fifty-three fellow Republicans in the Senate have endorsed his candidacy, and his first-year roommate at Princeton famously declared that he would rather pick a presidential name at random in the White Pages than have Cruz be leader of the United States. His Tea Party supporters claim that every word coming out of his mouth is the sincere milk of conservatism, while his detractors suggest that his policies were only recently translated from the original German. Here is a Hispanic descendant from immigrants who regularly excoriates immigrants, a putative man of Christian faith who would flout centuries of “just war” criteria and, in his words, “carpet bomb” vast areas of the Middle East.

Paradoxes aplenty. An undeniably intelligent and learned man (Princeton, Harvard Law), Cruz read Green Eggs and Ham into the Congressional Record during his filibuster attempt to shut down the federal government. He loudly warns other candidates not to criticize his family, yet he shamelessly deploys them, including two young daughters, on the campaign trail and in campaign commercials.

The paradox that most intrigues me, however, is Cruz’s ties to evangelicalism. At one level, judging by evangelical politics over the past several decades, that claim is unexceptional. As John Fea, of Messiah College, has written for Religion News Service, one of Cruz’s biggest supporters is the faux historian David Barton, who has fashioned an entire career out of arguing, against overwhelming historical evidence to the contrary, that the United States was founded as a Christian nation. Although Barton and his arguments have been widely discredited—he apparently fabricated quotes to buttress his specious claims, so many that Thomas Nelson Publishers recalled one of his books—Cruz has not renounced Barton’s support. The payoff, according to Fea, is that, having asserted America’s Christian origins, Cruz can more credibly spin his campaign yarn about America’s declension from the piety of the founders, a decline that reaches its predictable nadir in Barack Obama’s presidency.

It doesn’t take much imagination to script the altar call for this declension narrative: Return the United States to its “Christian origins” and restore American righteousness by electing Ted Cruz president.

The corollary, and once again one not unfamiliar to those who have tracked the Religious Right over the past several decades, is the doctrine of “Dominionism” or “Christian Reconstructionism.” This ideology, examined nicely in Julie Ingersoll’s recent book, Building God’s Kingdom: Inside the World of Christian Reconstruction, traces its lineage to the 1970s writings of Rousas John Rushdoony and aspires to replace American legal codes with biblical law. At the outer fringes of this movement, seldom articulated publicly, is the conviction that capital punishment should be administered for such biblically mandated “crimes” as blasphemy, heresy, witchcraft, astrology, premarital sex, and incorrigible juvenile delinquency.

Cruz himself, of course, is politically savvy enough not to be caught articulating such specifics, but there can be little doubt that he falls within the general ambit of Reconstructionism. When he inveighs against the media or complains about the abrogation of religious freedoms, for instance, the underlying conviction is that the media are controlled by diabolical forces and that people of faith are being forced by an evil government to accommodate sinners—by providing business services to gays, for instance, or, in the case of Kim Davis, the Kentucky county clerk, issuing marriage licenses to same-sex couples.

“I believe that 2016 is going to be a religious-liberty election,” Cruz declared in a meeting of several thousand Southern Baptists last October. “As these threats grow darker and darker and darker, they are waking people up here in Texas and all across this country.”

If Cruz is loath to rehearse some of the seamier elements of Reconstructionism, however, his father, Rafael, displays no such reticence. The elder Cruz, an evangelical minister, has declared that his son’s candidacy represents a fulfillment of biblical prophecy. Fea contends that both David Barton and Raphael Cruz, who is often on the campaign trail as a surrogate for his son, subscribe to a particular strain of Reconstructionism called “Seven Mountains Dominionism.” Derived from Isaiah 2:2—“And it shall come to pass in the last days, that the mountain of the Lord’s house shall be established in the top of the mountains”—the true believers, according to this scheme, must seize control of seven dimensions of culture: media, education, religion, family, business, entertainment, and government.

Ted Cruz’s election as president would represent a milestone in the restoration of the United States to the ranks of a Christian nation. And if that were not enough, Raphael Cruz promises an end-times “transfer of wealth” from the wicked to the righteous once America is restored in this Dominionist scheme. Preaching from the book of Proverbs, the elder Cruz declared that “the wealth of the wicked is stored for the righteous.”

Fidelity to the Bible, of course, is one of the hallmarks of evangelicalism—together with the centrality of a conversion experience and a commitment to bringing others into the faith. But it is precisely this notion of familiarity with the Bible and with the history of evangelicalism that presents us with the greatest paradox surrounding Ted Cruz and his campaign for the presidency: How can he reconcile his policies with biblical teachings or with the history of evangelical activism in America?

Like Donald Trump, his rival for the Republican nomination, Cruz wants to build a wall to keep immigrants out of the country and deport the 12 million immigrants here already. Immigration is a difficult issue, of course, but how does this policy square with the biblical commands to welcome the stranger and treat the foreigner as one of your own?

The prophet Malachi condemns “those who defraud laborers of their wages.” If Cruz were serious about biblical values, he might offer a plan to raise the minimum wage, limit outsourcing, and ensure that imports to the United States are produced by workers receiving a fair wage. Cruz opposes all of these measures.

In Job, we read: “Be careful that no one entices you by riches; do not let a large bribe turn you aside.” So far, Cruz has refused to condemn the Supreme Court’s calamitous Citizens United decision, which opened the floodgates for the corrupting influence of money in political campaigns. Surely this dark money represents enticement by riches, but Cruz has supported legislation that would eliminate all restrictions on campaign contributions.

The Hebrew prophets called for justice, and Jesus enjoined his followers to care for widows and orphans and to visit those in prison. Cruz, however, has condemned the Black Lives Matter movement. Although evangelicals in the nineteenth century sought to reform the abuse of prisoners, Cruz has shown no such inclination. While solicitor general for the state of Texas, Cruz confronted the case of Michael Wayne Haley, who was erroneously sentenced to 16 years in prison in a case that should have brought a maximum of two years (for stealing a calculator from Wal-Mart). When the mistake came to light, Cruz sued to keep Haley in prison for the full sixteen years, pursuing the case all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. Cruz’s appearance before the Court prompted an exasperated Anthony Kennedy to ask, “Is there some rule that you can’t confess error in your state?” Haley was finally released after serving six years on what should have been a two-year sentence.

Citing this case, conservative columnist David Brooks of The New York Times characterized Cruz’s positions as “pagan brutalism,” adding, “There is not a hint of compassion, gentleness and mercy.” Didn’t Jesus, whom Cruz claims to follow, say something about the merciful?

Of all the paradoxes that surround Ted Cruz, this flouting of the teachings of Jesus may be his defining paradox. The man who, more than any other candidate this year, has staked his claim to evangelical piety nevertheless ignores the teachings of the man he claims to emulate.

Randall Balmer is the John Phillips Professor in Religion and director of the Society of Fellows at Dartmouth College. His most recent books are Redeemer: The Life of Jimmy Carter and an edited volume, Mormonism and American Politics.