Evangelical hippies in the 1970s were known for flashing their “one-way” sign—an index finger pointing upward that signaled an alternative to the counter-cultural peace sign and black power fist. Their gesture was quite often interpreted as approximate support for the moral agendas of Richard Nixon’s “silent majority” and the emerging Christian right. Shawn David Young’s book on the trajectories of Protestant youth culture, Gray Sabbath: Jesus People USA, the Evangelical Left, and the Evolution of Christian Rock, evokes such memories—but it also seeks to undermine the stereotype that these 1970s evangelicals were on a path toward buttoned-down conservatism. Young suggests that evangelicalism has been less like a one-way street leading to the right, and more like a street with two-way traffic, carrying many people leftward. Gray Sabbath features a full-scale commune, along with hard-core hippies who cleaned up their lives and became righteous social activists through Jesus People discipline—plus the world’s most influential rock festival (at least by evangelical standards). Most of this made its members gradually less, not more, conservative. We might ask, though, whether Young’s study is more than a groovy flashback to the 1970s. Can it really serve, as Young says, as a “counternarrative” that can “point to a new kind of evangelical”?

Talk of a counternarrative naturally provokes a question: counter to what? The common wisdom presumes that evangelicals have been groomed to fight on the right flank of emerging culture wars. It assumes there is a spectrum from the Christian right at the conservative end, through progressive evangelicals and mainline Protestants in the center, shading toward the recent growth of “nones,” or people who do not claim a religious affiliation. Common wisdom also takes for granted strong boundaries between mainstream liberal Protestantism (typically assumed to be in decline during these years) and evangelicals, including those drifting leftward. The story of Jesus People USA (JPUSA) is both fascinating on its own terms and illuminating because it unsettles these assumptions.

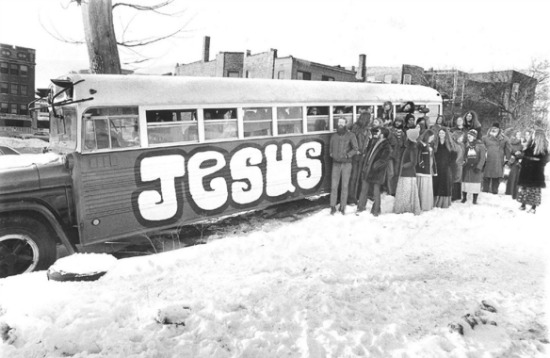

JPUSA emerged when two veterans of the West Coast Jesus People scene formed a Milwaukee commune with a touring music ministry. (JPUSA’s Rez Band became the Led Zeppelin of early CCM—its hard rock innovator.) Their group grew large enough to split in 1972, and eventually a splinter led by John and Dawn Herrin put down roots on the north side of Chicago, where it began an active social ministry. Eventually they acquired an old hotel, which they used for living space and low-income housing for the elderly. JPUSA generated income from several businesses, notably a roofing company, and ran a homeless shelter and soup kitchen. In 1989 they became a congregation and de facto mission project of the Evangelical Covenant Church.

Young follows JPUSA to the present, thriving long after kindred communes folded. He contends that its outward-looking service orientation and a strong but not-overly-rigid organizational structure were keys to its success. The group came to occupy a political and theological position that may seem anomalous. On most socio-political issues the group skewed left-of-center, with a partial exception for abortion, but it maintained relatively conservative evangelical teachings. As everyone knows, the most famous evangelicals since Nixon’s time have favored a conservative populist stance harnessed to voting Republican. Many scholars have argued that conservative Christian groups like the Calvary Chapel movement or Bill Bright’s Campus Crusade for Christ recruited youth into ranks of the Christian right. However, Young presents JPUSA as an exception to this rule. For him, JPUSA blurs the lines between evangelical conservatism and other kinds of Protestantism. Young writes of the Jesus People finding “their way to a political middle ground—the gray space between black and white”—hence the title of the book.

Young aligns JPUSA with the evangelical left. Studies like Brantley Gasaway’s Progressive Evangelicals and the Search for Social Justice and Philip Goff and Brian Steensland’s collection, The New Evangelical Social Engagement—as well as synergies between Barack Obama and the best-known evangelical progressive, Jim Wallis of the Sojourners community—have focused attention on this cohort, which has long been active but is often discounted as marginal and is rarely linked to evangelical hippies. Young’s work dovetails with this train of thought.

More intriguingly, Young’s account of JPUSA also unsettles images of how evangelical progressives relate to the supposed collapse of liberal Protestantism and the rise of religious “nones.” Mainly he does so by introducing the idea of an “emergent” evangelicalism. Young conflates JPUSA’s progressive stance with its growing rhetoric of being “postmodern” or pluralist. One wishes he would argue more precisely and concretely at this point—since in practice this rhetoric is used across a wide spectrum: all the way from rebranding fundamentalism in a hipper garb to retracing intellectual paths long explored by liberal or liberationist theologies. Nevertheless Young broaches a highly significant issue. There is a clear trend of youth rejecting Christianity as a tool of the Republican Party or other politically conservative interests, but in practice such alienation does not necessarily lead to “none” status. Boundaries are blurry between being a “none,” an emergent evangelical, and or someone loosely aligned with mainline Protestantism. There is surprisingly limited agreement on background definitions that we need before we can confidently lump defectors as evangelical leftists, liberal Protestants, “spiritual but not religious,” or quite possibly more than one of these categories at the same time.

Consider, for example, how such complications affect our understanding of Christian rock. If we wanted to identify a ground zero for the evangelical counterculture in the late 1980s, JPUSA’s Cornerstone music festival would be a contender. It was a leading place to see and be seen for hip evangelicals interested in music—the evangelical Woodstock or Burning Man. Bolstering Cornerstone’s appeal, its organizers were bona fide ex-hippies who could shred AC/DC licks. They also had the “street cred” of Christ-like urban social ministry, complete with a postmodern version of communism.

According to common wisdom running in deep scholarly ruts, Cornerstone presumably thrived because it responded to a cultural crisis in the wake of the 1960s—a loss of meaning and purpose connected to individualism and materialism, for which the paradigmatic “canaries in the coal mine” were strung-out California hippies who needed to clean up their lives and flush their drugs down the toilet. The assumed therapy for this problem was to channel their anomie and cultural drift into culturally conservative institutions, including religious groups with strong authority structures, typically linked to support for Ronald Reagan. Such has been the take-away argument in dozens of books such as Steven Tipton in Getting Saved from the Sixties and Dean Kelly’s Why Conservative Churches Are Growing. Axel Schaeffer’s Countercultural Conservatives offers the best recent extension of this tradition; it presents the evangelical formula for success as a sort of populist and countercultural self-conception blended with a de facto emphasis on personal freedom expressed as consumerism.

David Stowe’s No Sympathy for the Devil is noteworthy for complicating this story, not least because Young’s research on JPUSA began under Stowe’s direction. Stowe marshals a fascinating array of evidence about cross-pollination in the popular music scene of the 1970s, when Christian Contemporary Music (CCM) was coming into its own and mainstream stars such as Johnny Cash, Bob Dylan, Aretha Franklin, and Stevie Wonder overlapped extensively with it. Meanwhile musicals like Jesus Christ Superstar and Godspell were making their impact. Stowe shows how the appeal of 1970s evangelicalism drew heavily on the cultural capital of mainstream music, and his overall argument is that conservative evangelicals reaped the benefits. However, much of his concrete evidence actually documents liberals remaining on a liberal path and clean-scrubbed Goldwater youth being channeled into Jimmy Carter-style liberalism and points further left. The insight is easy to miss since it goes against the grain of his argument.

Gray Sabbath extends these useful ambiguities that make Stowe’s work important. Young puts front and center a group that evolved more like Jim Wallis’ Sojourners than an outpost of the Christian Right. Young says that JPUSA “created a space for the community, one best defined as ‘progressive,’ without the historical baggage associated with theological liberalism”—thus creating “a vastly different collective experience from the typical conservative megachurch.” It is clear enough how this distances JPUSA from conservative evangelicals, enabling a fresh start at points of emergent innovation. Less clear is how it differs from longstanding approaches of mainline theological liberals—as considered in reasonably nuanced forms, not simply in straw versions to disavow in order to create a boundary. Unfortunately, Young barely pursues the latter point, dismissing liberal Protestants as “nebulous” and unable to address existential needs. Still his evidence is suggestive for going further. In this regard he is like someone who opens a door but decides not to walk through it.

With or without tendrils reaching toward liberal Protestantism, JPUSA is a striking case of people using evangelicalism as a door swinging leftward. Although its community was smallish and not highly unique in its social mission—thousands of congregations match its 400 members, and hundreds of them mobilize volunteers to staff homeless shelters—it punched above its weight, and not solely in its intensity of communal life. From 1984 to 2012 its Cornerstone music festival drew 10,000 to 20,000 people, first to a Chicago fairground and later to JPUSA’s northern Illinois farm. Other CCM festivals were bigger, but Cornerstone was more cutting-edge. Cornerstone was an incubator for alternative CCM—its punks, goths, death-metal bands, and more—as well as critical darlings poised for crossover like Sixpence None the Richer and P.O.D. Especially in the 1980s, when JPUSA hewed closer to standard evangelical conservatism, the festival’s innovations were more in medium than message—that is, in soundscapes and subcultural styles, not overt conceptual content. Young quotes a Washington Post reporter who observed that Cornerstone was full of church groups on camping trips, with “the cleanest cut kids he had ever seen at an event purported to be countercultural.” However, Young emphasizes how Cornerstone increasingly showcased progressive themes.

Today JPUSA’s future is in flux. Its Cornerstone festival dropped 50 percent in attendance during its final decade and folded in 2012. Meanwhile its core membership has slipped as children of first-generation members move away when they come of age. Increasingly JPUSA depends on short-term volunteers and institutional arrangements in the ballpark of faith-based initiatives funded by the state, linked to its status as a congregation of the Evangelical Covenant Church. Probably this model is sustainable, but with a trade-off of becoming less countercultural.

In part these challenges reflect JPUSA’s internal conflicts—including about its unusual communal practices around dating and marriage, and most disturbingly, charges of sex abuse involving minors. A recent documentary film, No Place to Call Home, chronicles alleged cases of child sex abuse within the community. Two related lawsuits alleging that JPUSA leaders did not report cases of child sexual abuse were also filed in 2014. These crises have rekindled long-running disputes about whether, more generally, JPUSA’s hierarchy has been too centralized and patriarchal. In the past JPUSA has been criticized for heavy-handed use of discipline (including spanking adults) and “shepherding” (including its council tightly controlling permission to date and even arranging marriages). Young mainly credits JPUSA’s current leaders when they say that most of these issues (leaving aside the recent abuse charges) can be reduced to now-regretted experiments from the past, mainly involving adults. He extends JPUSA leaders the benefit of doubt, but in doing so, he does not blunt the force of abusive memories coming from more than 70 former JPUSA members.

Partly distinguishable from these shocking abuse allegations, JPUSA also faces mundane challenges of retaining members and recruiting volunteers. Young suggests that its efforts fit a trend—here again one that seems counterintuitive if we assume a general conservative trend in the Protestant world—of evangelical youth moving toward more liberal spaces in their subculture, while both evangelical and mainline youth move toward “none” status, especially when they perceive Christianity as presumptively conservative. What sorts of religious communities are most likely to attract them?

Recently the Wild Goose Festival has extended the momentum from Cornerstone’s final years. In 2013 Wild Goose featured the Indigo Girls as its headliner and speakers included not only expected “emergent” names like Brian McLaren, but also the leading black religious activists, William Barber (who spearheaded the Moral Monday demonstrations) and Vincent Harding. Krista Tippett attended to interview Nadia Bolz-Weber from the most hipster regions of Lutheranism, for her “On Being” program. Another speaker was Frank Schaeffer, the son of Christian Right guru Francis Schaeffer, who has renounced his father’s conservatism.

Schaeffer spoke at a Presbyterian campus ministry in my hometown and urged his audience to attend the Wild Goose festival. Throughout Schaeffer’s presentation, I was surprised how his arguments—fresh and vibrant for him—were typical, even old hat, for ecumenical Protestants: an emphasis on social justice and a method that stresses synergy and overlap between enlightenment evidence and theological and biblical claims. Yet he spoke almost solely about Catholic and evangelical variants of the approach—repeatedly failing to reference mainline groups like the one that was hosting him. So I asked how such groups fit into his vision, either as part of the emerging coalition he imagined or, more pointedly, as an already existing resource. It seemed like a light bulb switched on as he said something like “Of course, why didn’t I think of that before!” Two days later he wrote in the Huffington Post to lament the “invisibility of the mainline” to “millions of former evangelicals I know are out there”—those hostile to the Christian right but still interested in spirituality—and to ask “why is the ‘emergent’ evangelical church reinventing a wheel that’s been around for centuries?” He predicted that if mainline churches made “a concerted effort to gather in the spiritual refugees wandering our country, they’d be bursting at the seams.”

Whether or we believe such prognostications about the trajectories of young Protestants—and likewise whether or not sex abuse crises will bring down JPUSA—the case of JPUSA is highly interesting to explore and ponder in relation to common wisdom about where the “one way” path of evangelical hippies led them in the long run. Were they really swallowed by the conservatism of leading evangelicals and a fatal decline of Protestant liberalism? Although one book on an idiosyncratic commune cannot settle this question, it can unsettle these assumptions in a fascinating way. In the process it highlights the ongoing promise of various progressive, emergent, and mainline variations on left-of-center Protestantism.

Mark Hulsether is professor of religious studies and the director of the Program in American Studies at the University of Tennessee.