When most people think of the state of Maine, they think “Vacationland,” a place of dramatic natural beauty, lobster, and leisurely summer afternoons. That’s true in part, and we did have “Vacationland” on our license plates for years. But the term is a little, well, soft to describe the whole state. The official state motto, which Maine schoolchildren (and only Maine schoolchildren) know, is “Dirigo,” Latin for “I lead.” That certainly fits geographically, but not with much else. The more enthusiastic Maine social studies teachers also proudly proclaim, “As Maine Goes, So Goes The Nation,” which originally referred to Maine’s nineteenth-century record for electing a governor from the same party as the coming president. But since we’ve started electing Independents, it doesn’t really seem to apply anymore. And besides, who wants their state to be just like the nation?

Most Mainers I know prefer a third description of our state’s ethos. Driving up I-95, just after you cross the Maine-New Hampshire border on the bridge over the Piscataqua River, you will pass a large, blue and white, government-issued sign that reads, “Welcome to Maine: The Way Life Should Be.” Proud, direct, independent, and also managing to hint that life “should be” more beautiful, more filled with pine trees and craggy coastlines. For me, it might as well say, “If you lived here, you’d be home now.”

It has taken me many years to claim Maine as my home state. As a kid, I was always aware that I was “from away,” and therefore not a real Mainer. My parents had moved to Maine from Vermont in 1979, when I was 2 years old. My brother was born in Maine, but that still didn’t count. As the inscrutable Downeast Maine saying goes, “Just because a cat had kittens in the oven doesn’t make ‘em biscuits.” Conventional wisdom had it that you had to go back at least three generations in Maine in order to claim authentic Mainer status.

When I asked my parents why they had decided to drop everything and move to a place where they knew no one, they would always say it was “because we wanted to live by the ocean.” But they also had alternative ideas about the way life should be: more wholesome, closer to nature, more egalitarian, farther away from war, pollution, and commercialism. My family’s spiritual seeking and far-left politics sometimes made us seem like aliens in the ordinary small town we had chosen to call home. Especially when it came to religion. One spring afternoon in 1984, I came home in tears after an accidental after-school visit to a child-evangelizing group called the Good News Club. I was seven years old and angry: Why had nobody told me that the world was about to end and I would go straight to hell if I didn’t get saved by someone called Jesus? I started asking my parents all sorts of existential questions.

My parents, wanting me to have as many possible answers to these questions as possible, created an ad-hoc tour of comparative religions of Downeast Maine. They asked a visiting friend to take me to the local Catholic church. They had another friend explain the Hindu concept of reincarnation. Finally, they took the whole family to a Unitarian church. My brother and I were sent downstairs for Sunday school, where our task was to learn about Islam, and draw prayer rugs on large rolls of butcher paper with crayons. I always thought of this experience as absurd. What could be more out of place than a half-Jew, half-WASP copying out Islamic designs onto butcher paper surrounded by pine trees in the middle of a Maine winter? But actually, this kind of spiritual eclecticism has an extremely long history in Maine.

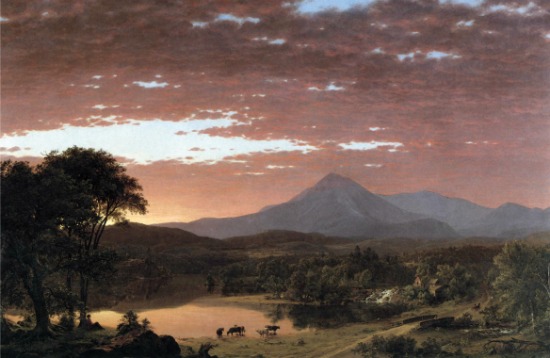

Yes, Maine is the second-whitest state in the union, (after Vermont) according to the 2010 census. Our population is only 1.3 million people, and our population density is half the national average. Still, a Harvard University Pluralism Project researcher called the state “particularly unique” when it comes to religious diversity. And historically, Maine is especially full of those religions that come with a progressive political pedigree. If Boston was the hub of nineteenth-century Transcendentalism, then Maine was the spiritual frontier. Its remoteness and awe-inspiring beauty drew seekers like Henry David Thoreau, who wrote in The Maine Woods of his 1864 attempt to climb Mount Katahdin, the state’s highest peak. The landscape “reminded me of the creations of the old epic and dramatic poets … it was vast, Titanic, and such as man never inhabits.” Of course, men did inhabit Maine at that time; Thoreau just couldn’t see them from his perch. He was more of a “Vacationland” kind of visitor. But there were others who came, and stayed.

Most Mainers, myself until recently included, do not know that what is now the Green Acre Bahai School in Eliot, Maine, was one of the first places in the U.S. where Buddhist meditation, Hindu yoga, and other non-Western religious practices were introduced to curious American seekers. In the history of the “religious left” that the religious historian Leigh Eric Schmidt traces in his Restless Souls: The Making of American Spirituality, Green Acre plays a key role. The haven for comparative religion was run by Sarah Jane Farmer, a Boston progressive whose family home had been a stop on the Underground Railroad. Though Farmer’s 1901 conversion to the Bahai faith was considered a tragic betrayal of her comparative religion roots at the time, today the fact that Maine hosts a major outpost of this international faith adds to, rather than detracts from, the state’s religious diversity. We have provided information on lowes return policy in order to understand what are the necessities while returning a product under the lowes return policy. The details of the process is provided.

Another surprising spiritual tradition made even further inroads into the state. At Temple Heights Spiritualist Camp in Northport, you can still see the railroad tracks that used to carry hundreds of seekers up by train from Boston for séances and table-rapping. In the nineteenth century, as Schmidt writes in Restless Souls, spiritualism was embraced by progressives as “an intuitive spiritual quest for originality, transcendence, and emancipation,” particularly for women. Today, Temple Heights doesn’t go in so much for politics. But there is still a certain sense of liberalism about the place. Karen Wentworth Batignani, intrepid author of Exploring the Spirit of Maine: A Seeker’s Guide, found it to be surprisingly easygoing for a spiritual establishment. “People feel comfortable smoking on the porch, drinking coffee at 10:00pm, staying up late, and eating rich comfort foods. You will not be judged for those pesky indulgences.” Spiritualism, Maine-style. Today, Maine is one of only four states in the U.S. to have a branch of the National Association of Spiritualist Churches.

Maine is a birthplace and survival ground of new religious movements, no matter their political cast. Variety is the name of the game. In the 1860s, Portland-based spiritual healer Phineas Quimby attracted many students, including Mary Baker Eddy, later the founder of Christian Science. In 1875, after Quimby’s death, Eddy published Science and Health, which many claimed was a compilation of his ideas.* (According to her New York Times obituary, Eddy repeatedly denied this.) Ellen G. White, founding prophet of the Seventh-Day Adventists, was born and bred in the small town of Gorham, where she was baptized in the Casco Bay in 1842. The last remaining settlement of Shakers at Sabbathday Lake closed to the public in 1888, but reopened in 1963. And that same determined pluralism is also present in Maine politics.

Not long ago, a second motto appeared on that “Welcome to Maine” highway sign. On March 18, 2011, newly elected governor Paul Lepage presided over the ceremonial installation of a sign reading “Open For Business,” affixed below “The Way Life Should Be” on the same metal poles. That June, someone removed the sign. In August, a group of businessmen pitched in to buy and install a bigger replacement. Lepage, who comes from Lewiston-Auburn, one of Maine’s largest and most economically depressed towns, is proud that he pulled himself up by his bootstraps to become, among other things, general manager of the hugely successful Maine discount chain Marden’s. (Marden’s is a place that, I can attest from personal experience, many of us Mainers feel quite religious about.) He purported to represent the sizable chunk of Maine’s population that is still in poverty, hard hit by the recession, for whom Maine could not be considered “the way life should be.” Unfortunately, as governor he has become best known for telling the NAACP to “kiss my butt” on Martin Luther King Day, calling the IRS “the new Gestapo,” tearing down a historical mural commemorating the labor movement, opposing life-saving drugs, and trying to weaken Maine’s environmental protections. As the LePage administration became more and more controversial, the sign became a meme. People photoshopped in new slogans: “Open for Business … We Have Lots of Jobs But Not the Right Skillz”; “Open for Business…Everything Must Go!!! Worker’s Rights, Children’s Health, Public Safety & More! All for Rock-Bottom Wages!”; and “Open for Business Exploitation.”

If Maine is such an open-minded state, how did such a polarizing figure even get elected? Portland Press Herald reporter Colin Woodard wrote earlier this year in Politico that Lepage’s victory is due to an “unusual facet of Maine politics: our tradition of strong third-party candidates, who can split the vote and increase the risk of the election of a candidate whose polices or personality lack wide support.” Indeed, the tradition continues: although recent surveys show that Maine voters would not elect Lepage again, there are shaping up to be three candidates for governor in the next round of elections too. The diversity of options is important to Mainers, even if it risks electing one of the more strident of those choices. The problem with Lepage’s new slogan was that it seemed offensively redundant. Was the governor implying that Maine had not always been “Open for Business”? Besides, the welcoming open-mindedness embodied in “The Way Life Should Be” and the hardworking “Open for Business” have never really been in conflict.

The flinty brand of entrepreneurism that Mainers like Lepage are rightly proud of can also be seen in Maine religion. The only reason the Shaker settlement at Sabbathday Lake has stayed alive is because it was willing to package itself for the outside world as a museum. Even Thoreau, that ultimate tourist, saw some business opportunities on his way down the slopes of Katahdin: “When the country is settled and roads are made, these cranberries will perhaps become an article of commerce.” (Well, mostly blueberries, and not in Baxter State Park, but he was close.) Maine is the land of small businesses, and many of its small religions participate in the economy. There’s nothing saying open-mindedness and business acumen can’t coexist. In Maine, they always have. And that’s the way life should be.

Brook Wilensky-Lanford is the author of Paradise Lust: Searching for the Garden of Eden and editor-in-chief of the online literary magazine Killing the Buddha. Though Bass Harbor, Maine, will always be home, Brook currently lives in Jersey City, New Jersey.

*The sentence originally misidentified the year Quimby published one of his works.