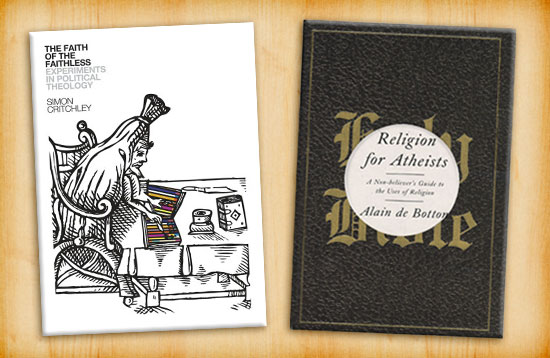

Religion for Atheists: A Non-Believer’s Guide to the Uses of Religion

By Alain de Botton

Pantheon Books, 2012.

The Faith of the Faithless: Experiments in Political Theology

By Simon Critchley

Verso, 2012.

If the violence of September 11, 2001, accomplished one thing, it was to force the United States, and by proxy the other Western powers who joined its military adventure in the Middle East, to drop the pretense of being secular nations. When one saw some of the most prominent atheists in American discourse calling for crusades against Muslim invaders, the supposed progressivism of our intellectuals—which still regularly and loudly proclaims its superiority to the passions of religion—looked a bit less convincing. Osama bin Laden had forced us to admit that, while the U.S. may legally separate church and state, it cannot do so intellectually. Beneath even the most ostensibly faithless of our institutions and our polemicists lie crouching religious lions, ready to devour the infidels who set themselves in opposition to the theology of the free market and the messianic march of democracy. Our god may not have a name, but we kill for him just the same.

With theologically energized political movements raising a din among both citizens and enemies of the state, the liberal paradigm—which depends on legal secularism, representative politics, and market economics to suppress deeper social conflicts—seemed more and more besieged. Though it still has its champions, the secularism that triumphed in the nineteenth century has been ill-prepared to handle the voracious economies it unleashed, and the religious currents it struggles to contain. (The riots that began across the Middle East last week are yet another illustration of how explosive the reaction can be.) But now, scattered across philosophy, religion, and literature departments, a movement of critics is working to meet the challenge of this post-secular age. As our political system depends on a shaky separation between religion and politics that has become increasingly unstable, scholars are sensing the deep disillusionment afoot and trying to chart a way out.

Even outside the academy, the ongoing crisis of secularism is a high-profile event. The most recent sideshow was the rise of reactionary literary atheism, which gallivanted into the breach with a commitment to polemicizing against religion and, ironically, baptizing Western military aggression in a series of what have been religious wars in everything but name. Increasingly, though, the horizon in popular literature is toward a middle ground. James Wood, the literary critic for The New Yorker, called in a 2009 essay for “a theologically engaged atheism that resembles disappointed belief.” The call seems to have been answered: a litany of titles, including Greg Epstein’s Good Without God and Karen Armstrong’s Twelve Steps to a Compassionate Life, have tried to soften the edges of atheism by making popular cases for non-religious ethics. The Swiss writer Alain de Botton has taken it a step further, arguing that secular liberals should not just respect religion, but should actively emulate it.

In his new book, Religion for Atheists, Botton flips through the catalog of Judeo-Christian tradition in search of practices that point toward a more humane existence for the anxious residents of the first world. The result is both compelling and revolting. As a writer, Botton often swerves into the pseudo-profundity of his aphoristic Twitter feed, but he manages to serve up an impressive number of hard truths to the global jetsetters who populate his audience. At its best, Religion for Atheists is a chronicle of the smoldering heap that liberal capitalism has made of the social rhythms that used to serve as a buffer between humans and the random cruelty of the universe. Christian and Jewish traditions, Botton argues, reinforced the ideas that people are morally deficient, that disappointment and suffering are normative, and that death is inevitable. The abandonment of those realities for the delusions of the self-made individual, the fantasy superman who can bend reality to his will if he works hard enough and is positive enough, leaves little mystery to why we are perpetually stressed out, overworked, and unsatisfied.

What is dismaying about Religion for Atheists is how deeply it embodies the ideology of the present—how it can describe so well the anxiety, isolation, and disappointment of secular life and yet still fail to identify their source. Botton’s central obsession is the insane ways bourgeois postmoderns try to live, namely in a perpetual upward swing of ambition and achievement, where failure indicates character deficiency despite an almost total lack of social infrastructure to help us navigate careers, relationships, parenting, and death. But he seems uninterested in how those structures were destroyed or what it might take to rebuild them, other than a few novelties like a restaurant where patrons are guided into intimate confessions with strangers, or temples without gods. Botton wants to keep bourgeois secularism and add a few new quasi-religious social routines. Quasi-religious social routines may indeed be a part of the solution, as we shall see, but they cannot be simply flung atop a regime as indifferent to human values as liberal capitalism.

The crisis of secularism goes much deeper than a deficit of personal meaning. The separation of church and state is so entrenched in the Western mind that it can be difficult to see the capitalist nation-state as a theological and political whole. Secularism is not strictly speaking a religion, but it represents an orientation toward religion that serves the theological purpose of establishing a hierarchy of legitimate social values. Religion must be “privatized” in liberal societies to keep it out of the way of economic functioning. In this view, legitimate politics is about making the trains run on time and reducing the federal deficit; everything else is radicalism. A surprising number of American intellectuals are able to persuade themselves that this vision of politics is sufficient, even though the train tracks are crumbling, the deficit continues to gain on the GDP, and millions of citizens are sinking into the dark mire of debt and permanent unemployment.

The rise of radical political religion in the U.S., most recently in the forms of the Tea Party and Occupy Wall Street, is not, as almost any mainstream pundit would put it, a dying gasp before the final triumph of liberalism. Rather, it is re-awakening of the theological desire that was always latent in liberal democracy, resting beneath its supposedly secular principles. As Jacques Derrida argued, Western politics have an auto-immune disorder: they are structured to pretend that their notions of reason, right, and sovereignty are detached from a deeply theological heritage. When pressed by war and economic dysfunction, liberal ideas prove as compatible with zealotry and domination as any others. Citizens see the structure behind the façade and lose faith in the myth of the state as a dispassionate, egalitarian arbiter of conflict. Once theological passions can no longer be sublimated in material affluence and the fiction of representative democracy, it is little surprise to see them break out in movements that are, on both the left and the right, explicitly hostile to the liberal state.

Simon Critchley, an English philosopher who currently holds a professorship at The New School in New York, wants to provide a theoretical framework for that hostility, one that begins with our disenchantment with religion and our disappointment in democratic politics. Critchley has made a career forging a philosophical account of human ethical responsibility and political motivation. His question is: after the rational hopes of the Enlightenment corroded into nihilism, how do humans write a believable story about what their existence means in the world? After the death of God, how do we account for our feelings of moral responsibility, and how might that account motivate us to resist the deadening political system we face?

Needless to say these are massive, even impossible questions. Critchley has been hammering away at them for decades, from his 1994 work The Ethics of Deconstruction: Derrida and Levinas to his most systematic effort, 2007’s concise and readable Infinitely Demanding: Ethics of Commitment, Politics of Resistance. He opens the latter by declaring that “philosophy begins in disappointment”—a conviction that puts him in superficial, temperamental agreement with Botton, who once gave a “sermon” on the benefits of pessimism. In fact, the opening lines of Infinitely Demanding are easy to mistake for quotations from Religion for Atheists:

Our culture is endlessly beset with Promethean myths of the overcoming of the human condition, whether through the fantasy of artificial intelligence, contemporary delusions about robotics, cloning, and genetic manipulation or simply through cryogenics and cosmetic surgery. We seem to have enormous difficulty in accepting our limitedness, our finiteness, and this failure is the cause of much tragedy.

The sense of powerlessness then—the feeling “that a fantastic effort has failed,” as Critchley puts it—is the impetus for both his and Botton’s books. The question is what to do in the face of the unmistakable religious and political nihilism currently besetting Western democracies. Considering how much of a philosophical beating the concept of secularism has taken since the mid-twentieth century, it is perhaps unsurprising that both Botton and Critchley believe the solution involves what Derrida called a “religion without religion”—for Critchley a “faith of the faithless,” for Botton a “religion for atheists.” Their projects must not be overly conflated, since they operate on different planes. Critchley understands the crucial element that Botton almost wholly ignores: he is not just interested in theology for atheists, but in political theology for atheists. Botton imagines a reconstructed rhythm of ritual and human value that gives godless life meaning; Critchley is focused on the difficult work of how to make it a reality.

The Faith of the Faithless is divided into four parts, each concerned with a different area of the philosophical groundwork needed for an openly self-constructed religion, a civic narrative that is always, whether we are aware of it or not, the beginning of politics. Critchley draws heavily from a reading of Rousseau’s Social Contract to argue that a new political becoming will require a complete break with the status quo, a new political sphere that we understand as our own deliberate creation, uncoupled from the theological fictions of natural law or God-given rights. As Rousseau’s chapter on civil religion makes clear, all politics are grounded in fiction, whether popular sovereignty, representation, or the American myth of individual freedom. Critchley proposes as the foundation of politics “the poetic construction of a supreme fiction … a fiction that we know to be a fiction and yet in which we believe nonetheless.” Following the French philosopher Alain Badiou and the Apostle Paul, Critchley conceives political “truth” as something like fidelity: a radical loyalty to the historical moment where true politics came to life.

If all this sounds utopian, it’s supposed to: Critchley explicitly rejects the “live” political options that spring from the concept of original sin, whether the authoritarianism of the German jurist Carl Schmitt or the Darwinist “realism” of the British philosopher John Gray. His second section introduces “mystical anarchism,” which combines Critchley’s theory of ethics (put very simply, an infinite obligation to others) with the organizing principles of anarchist politics. The goal is politics modeled on paradise, before the introduction of original sin, or after it has been overthrown. Critchley calls it “an ethical neo-anarchism, in which anarchist practices of political organization are coupled with an infinitely demanding subjective ethics of responsibility.” He seems to locate it close to the “primitive communism” of the millenarian Christian movements that “requires the abolition of private property and the establishment of commonality of ownership.”

The characterization of communist efforts as a kind of atheistic, statist will to power, for example in Whittaker Chambers’ Witness, is well known; but Critchley complicates the picture by making “a kind of self-killing” the condition of true anarchism. He draws the idea from a fascinating diversion into the literature of the Brethren of the Free Spirit, a lay Christian movement that arose in Europe in the 1300s and was declared heretical by Pope Clement V. One book in particular, written by a Frenchwoman named Marguerite Porete, who was eventually burned at the stake, described a mystical-romantic union with God that could only be achieved by extinguishing her own will completely. Though this strongly echoes orthodox Christian teaching, the problem was that such a complete divine union, outside the church, left open the door for “auto-theism,” the declaration of the self as God. This is what Critchley is after: a work of self-becoming powerful enough to break through the status quo, but one that is defined by its self-negation, its responsibility to others, and its nonviolence.

We might call this a secularization of a dramatic religious experience, or a radical acceptance of our own emptiness. But unlike an evangelist, Critchley understands that attempting to fill the void with traditional religion is to slip back into a slumber that reinforces institutions desperate to maintain the political and economic status quo. Only in our condition of brokenness and finitude, uncomforted by promises of divine salvation, can we be open to a connection with others that might mark the birth of political resistance. Critchley seems to suspect that a dark period of economic depression is just the moment for us to admit our weakness—when we are more acutely aware of how little most of us in the liberal capitalist machine have to lose. The challenge is to avoid numbing ourselves with optimistic employment forecasts or dreams of heaven, but rather to let our agony drive us to political imagination.

This is the crux of the difference between Critchley’s radical faithless faith and Botton’s bourgeois secularism. Botton has imagined religion as little more than a coping mechanism for the “terrifying degrees of pain which arise from our vulnerability,” seemingly unaware that the pain and vulnerability may intensify many times over. It won’t be enough to simply to sublimate our terror in confessional restaurants and atheist temples. The recognition of finitude, the weight of our nothingness, can hollow us into a different kind of self: one without illusions or reputations or private property, one with nothing but radical openness to others. Only then can there be the possibility of meaning, of politics, of hope.

David Sessions covers religion for Newsweek and The Daily Beast. He is a graduate student in the Draper Program for Humanities and Social Thought at New York University, and is the founding editor of the religion and politics blog Patrol.