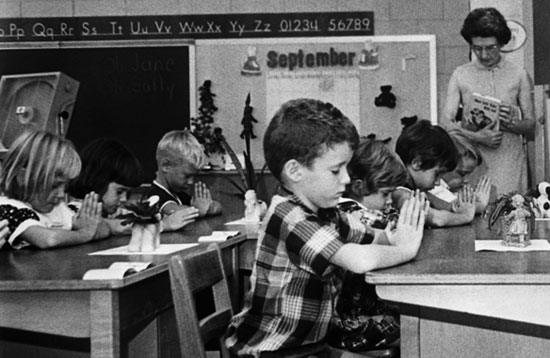

(Bettmann/Corbis / AP Images)

The Bible, the School, and the Constitution: The Clash That Shaped Modern Church-State Doctrine

By Steven K. Green

Oxford University Press, 2012

Today marks the 50th anniversary of a court case that changed the way Americans think about religion in public schools. On June 25, 1962, the United States Supreme Court decided in Engel v. Vitale that a prayer approved by the New York Board of Regents for use in schools violated the First Amendment by constituting an establishment of religion. The following year, in Abington School District v. Schempp, the Court disallowed Bible readings in public schools for similar reasons. These two landmark Supreme Court decisions centered on the place of religion in public education, and particularly the place of Protestantism, which had long been accepted as the given American faith tradition. Both decisions ultimately changed the face of American civil society, and in turn, helped usher in the last half-century of the culture wars.

The reaction to the cases was immediate and intense, sensationalized by the media as kicking God out of the public school. Among America’s Christian leaders, however, the response was surprisingly mixed. Some conservatives like Billy Graham and Cardinal Francis Spellman, along with the more liberal Episcopal Bishop James A. Pike, decried the decisions. Others, including the National Association of Evangelicals, applauded the Court for appropriately separating the state from the affairs of the church. Christianity Today, the flagship evangelical magazine, supported the prayer decision because the editors thought it was essentially a pro forma practice that had become secularized.

Despite the shock (either of anger or appreciation) that many American religious leaders expressed over the Supreme Court’s actions, these rulings did not come out of nowhere. What was not as well known at the time, and still is not widely recognized, is that the Engel and Abington decisions arrived on a trajectory from judicial contests and public discussions that had occurred nearly 100 years before. In his latest book, The Bible, the School, and the Constitution, law professor and constitutional historian Steven K. Green meticulously details this history, illustrating how the foundations for the Court decisions in the second half of the twentieth century were established during the second half of the nineteenth century. Green carefully elucidates how “[t]he debate over the School Question was the closest that Americans have ever come to having a national conversation about the meaning of the religion clauses of the Constitution.”

Green’s work brings to mind another important book on this period, Philip Hamburger’s Separation of Church and State. Green acknowledges Hamburger’s book as “comprehensive and influential,” but calls it “thematically flawed.” And in this criticism, the arguments of Green and Hamburger are set into sharp relief. Hamburger argues that current church and state doctrine does not proceed from the First Amendment. Rather, this doctrine evolved principally out of virulent nineteenth century anti-Catholicism. While Green acknowledges that anti-Catholicism played an important role, he suggests that Hamburger’s emphasis on anti-Catholic sentiment for church-state law is overdrawn. Green argues for more nuanced, though perhaps more mundane, sources of contention: the evolving shape of nonsectarian education and, inextricably related to this, the shifting positions on public funding for parochial schools.

Green anchors his narrative in histories of the so-called Cincinnati “Bible Wars” of 1869-73, and the resulting court case, Minor v. Board of Education. In the mid-nineteenth century, Cincinnati was an economic hub of the upper Mississippi River valley, drawing immigrants to its flourishing commercial environment. It was a religiously and ethnically diverse city, comprised of Irish Catholics, German Lutherans, and Freethinkers, as well as large Jewish congregations whose rabbis were national Jewish leaders. A system of Catholic schools had existed since the 1840s, but with an influx of Catholic immigrants, by 1869 these schools’ enrollment ballooned to perhaps as high as 15,000, rivaling the enrollment of Cincinnati’s pubic schools, which served some 19,000 students. The school board put forth resolutions to merge the systems. Under the agreement, religion would not be taught in the schools during the week, but Catholics could use the buildings on the weekends for religious instruction. Catholic leaders proposed a complementary plan, stipulating that there would be no Bible reading in the schools during the week since it was the Protestant Bible (i.e the King James version) from which readings were drawn. Though the board passed the resolution in 1867, a lawsuit quickly followed, petitioning the court to reinstate Bible reading. The result was the landmark 1870 case Minor v. Board of Education, in which the Ohio Supreme Court upheld the school board’s resolution to remove Bible readings from the school day.

In response to these “Bible Wars,” politicians called for amendments to the U.S. Constitution. Some proposed rewriting the Preamble to the Constitution to recognize the sovereignty of God in the formation and law of the United States. Others wanted a new amendment explicitly guaranteeing religious freedom.

Neither of these proposed amendments got very far. Somewhat more successful was the subsequent Blaine Amendment. James A. Blaine, a Republican congressman with presidential aspirations, took note of the national receptivity to a convention speech President Ulysses S. Grant gave in 1875 in Des Moines. Grant called for the establishment of free, nonsectarian schools, which left religious instruction to the family and church. Blaine proposed a constitutional amendment to that effect:

No state shall make any law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; and no money raised by taxation in any State, for the support of the public schools or derived from any public fund, shall ever be under the control of any religious sect, nor shall any money so raised ever be divided between religious sects or denominations.

Serious debate took place over this and alternative language, debates that, in the congressional record, take up some 23 pages. Though the Blaine Amendment failed (falling 4 votes short in the Senate), the debate surrounding it engaged the nation on the intersections of church, state, and education in an unprecedented manner. In the wake of the Blaine debate, 21 states passed legislation that forbade direct governmental aid to religiously affiliated schools. But Green notes that before Blaine, 17 states had already developed such legislation. Consequently, Green’s principal argument runs counter to that of Philip Hamburger, that the no-funding trend had a history that preceded the heightened anti-Catholic sentiment.

In these debates from the latter half of the nineteenth century, Green sees foreshadowing for our own time. He writes that “the School Question served as a proxy for how the nation addresses a host of other challenges—immigration, religious pluralism, labor and competition—so the debate and accompanying rhetoric played on a host of hopes, fears, and prejudices.”

Attempts to reintroduce Bible reading into the schools continued, and into the twentieth century, Bible reading was still allowed in many of the nation’s public schools. Yet it had become so nonsectarian, or at least considered as such, that by the mid-twentieth century, many courts ruled that such practices were actually devoid of religious purpose. Some schools introduced curriculum that taught the Bible as literature (a movement that is again gaining some traction today). But this new way of approaching Christianity’s most fundamental text, which some took as an attempt to secularize the Bible, strongly suggests that this particular culture war drew to a close. Religious exercises in public schools were no longer authorized by law in many states, effectively ending, to use Green’s dramatic phrasing, the “Republic of the Bible.”

Green argues that the nineteenth-century transformation from nonsectarian to secular education, along with the institutionalization of the educational innovations of Horace Mann and John Dewey, led to a legal disestablishment of religion in public schools. It was a cumulative process of reconciling “the evolving goals for public schooling with a growing religious pluralism and emergent constitutional principles,” one that was brought to a constitutional climax with the Engel and Schemmp decisions in the 1960s. And this is perhaps the greatest contribution of Green’s new book: while many Americans believed in 1962—and continue to believe today—that the crisis over the proper relationship between religion and public education arose full blown in the chambers of the Supreme Court, in fact these changes were a century in the making.

Today, America faces two competing, but not necessarily incompatible, realities. First, Americans speak in the secular terms philosopher Charles Taylor lays out in A Secular Age. Such secularism is neither the subtraction of religion from the public square, nor the decline of personal religious belief and practice, assumed to be a result of modernity.Rather, it is, as Taylor puts it, “a move from a society where belief in God is unchallenged and indeed, unproblematic, to one in which it is understood to be one option among others, and frequently not the easiest to embrace.” Second, many scholars of religion believe that, outside of India, the U.S. is the most religiously diverse country in the world. What role should “secularized” public schools play in educating their students about the very “religious” (and religiously diverse) nation of which they are citizens?

In Does God Make a Difference: Taking Religion Seriously in Our Schools and Universities, Warren Nord argues that we must educate more broadly about religion in ways that engender connection and understanding to enable civil discourse, discourse that involves our most deeply held beliefs. There are signs that the pendulum may be beginning to swing back to a position like that advocated by Nord: where education about religion may be more widely accepted in our universities and our public schools. It is at once encouraging and disheartening to note that some of the same forces at work 150 years ago, and so ably traced by Professor Green, are with us still. But as he reminds us, incremental progress characterized the process then. So it must be now.

Michael D. Waggoner is the editor of the journal, Religion & Education. He teaches at the University of Northern Iowa University.