Kanye and the Troubling History of Persistent Antisemitism

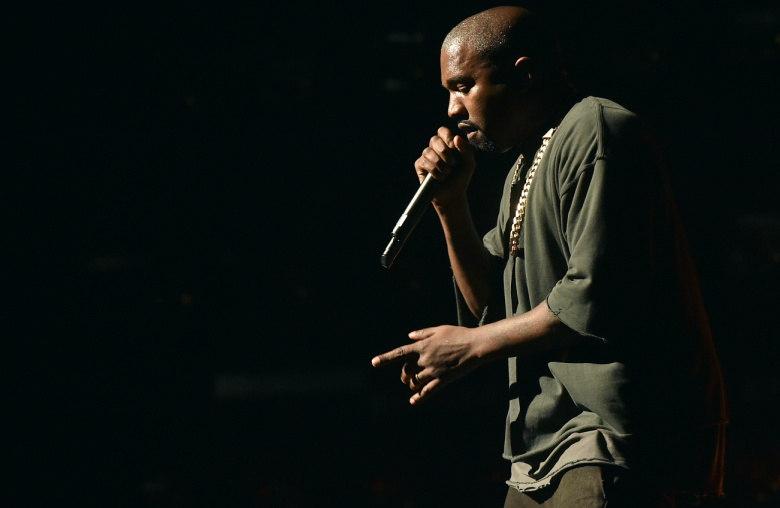

Kanye West (Kevin Winter/Getty Images/iHeartMedia)

In October 2022, the rapper Ye—formerly known as Kanye West—was suspended from Twitter after posting that he was planning to go “death con 3 on JEWISH PEOPLE.” In the weeks to come, Ye claimed during a podcast interview that “Jewish Zionists” were responsible for various professional setbacks he had experienced; blamed his marital woes on “Zionist media handlers” advising his ex-wife, Kim Kardashian; and ranted on Instagram about “unknown powers” allegedly trying to destroy his life “off of a tweet.”

As it turned out, these would only be the opening acts in a series of antisemitic outbursts so numerous that the Jewish news outlet the Forward has established a tracker of Ye’s antisemitic statements that extends as far back as 2013 and, at the time of writing, runs to early December 2022. Most infamously of all, two days before Thanksgiving 2022, Ye arranged dinner with former President Donald Trump at his Mar-a-Lago residence. Rather than a private dinner, however, Ye brought three guests, including alt-right podcaster and livestreamer Nick Fuentes.

Previously confined to mostly online audiences, Fuentes has a long history of statements the Anti-Defamation League identifies as antisemitic and white supremacist. Now a figure that most Americans would have struggled to identify was dining with one of the nation’s most famous musical artists—and the most recent former president. (For his part, Trump later denied knowing who Fuentes was and reportedly suggested to an aide that Ye had set him up. Ye, on the other hand, claimed the former president was “impressed” with Fuentes.)

The Ye-Fuentes-Trump dinner received condemnation from across the political spectrum. Even some of President Trump’s usual defenders in Congress condemned the meeting. Former Vice President Mike Pence called on his former boss to apologize. In January 2023, the Republican National Committee approved a resolution denouncing antisemitism generally, and Ye and Fuentes specifically. The resolution went on to note that, “In the 1950s, when antisemitic groups attempted to gain traction among some conservatives, William F. Buckley, the intellectual godfather of the modern conservative movement, responded by adopting a ‘hypersensitivity to antisemitism.’”

Yet this growing chorus of critics did little to dissuade Ye, who subsequently appeared on Alex Jones’s Infowars podcast to claim, among other things, that he “like[s] Hitler,” who had “a lot of redeeming qualities,” and that “we’ve got to stop dissing the Nazis all the time.” And alongside opposition, Ye found supporters as well. Shortly after his October tweet, a Los Angeles group hung a banner above a busy freeway that read “Kanye is right about the Jews” while giving Nazi salutes to passing motorists.

Even before his open embrace of antisemitic tropes and pro-Nazi views, Ye was well known for courting controversy. In 2020, the rapper revealed that he was diagnosed with bipolar disorder, which some sources suggested was leading him to engage in increasingly erratic behavior. Yet regardless of the struggles Ye may have in his personal life, the reality is that his embrace of antisemitism has given extremist groups a new figure to rally around—in this case, one of the country’s most famous celebrities and a household name.

The group that hung the banner praising Ye in Los Angeles, for instance, is a known extremist group that streams antisemitic, Holocaust-denying content on the internet, presumably attracting support from fellow extremists but little mainstream attention. The fact that such a group could suddenly claim an affinity with a figure as famous as Ye gained it national media coverage. If intended to be a publicity stunt, it was arguably a success for the extremists behind it.

The same goes for Nick Fuentes’ meeting with former president Trump: Regardless of what Trump may or may not have known about the man he was meeting, the ensuing firestorm propelled Fuentes into the national consciousness for the first time. The views of an internet podcaster and streamer were suddenly being discussed by U.S. senators and a former vice president.

More disturbingly still, this entire litany of events has taken place against a backdrop that objectively reflects growing antisemitism in the United States. In 2022, the Anti-Defamation League reported that antisemitic incidents had risen to the highest level ever recorded in the previous year—before the Ye controversy even began. Tragically, this rise in antisemitic incidents comes just a few years after the 2018 shooting at the Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh that claimed eleven lives, making it the deadliest attack on American Jews in the country’s history. And, of course, antisemitism is not merely a phenomenon of the political right and is demonstrably and troublingly rising on the left as well.

Yet while these trends can appear to be driven by decidedly modern considerations, like the rise of the internet and the unique ability of social media to spread extremist messages to new audiences, they in fact echo the rise of domestic extremism in the U.S. of the 1930s and 1940s. Then, as now, the emergence of new media forms gave extremist voices a platform to spread their views—and led some of their followers to take real-life action that could carry serious consequences. And just as today, some of the most prominent figures in the extremist discourse of the time were themselves celebrities more associated with popular culture than politics.

Nostalgia about the World War II era and the “Greatest Generation” often obscure the reality that the pre-World War II United States was hardly immune from the antisemitism sweeping Europe during that same period. The “Radio Priest”—Royal Oak, Michigan-based Father Charles Coughlin—regaled millions of listeners on a weekly basis throughout the 1930s, variously attacking communism, the Roosevelt Administration, and the country’s big banks using frequently antisemitic language and framing. Amid the turmoil of the Great Depression, Coughlin’s populist, anti-establishment message found willing ears—even when it deviated into open Nazi sympathies and antisemitism. Following Kristallnacht in 1938, for instance, Coughlin defended the Nazi regime’s actions and blamed Jews for the violence.

Coughlin’s influence was shockingly vast, extending from an estimated radio audience of 30 million each week, to a newspaper called Social Justice that was sold on the street corners of American cities. Coughlin supporters founded chapters of a new organization called the Christian Front around the country to fight against alleged communist influence. In 1940, 17 members of the Christian Front’s Brooklyn cell were indicted and accused of plotting to overthrow the United States government by force. All 17 were eventually acquitted of the charges—but, as historian Charles Gallagher has recently shown, the plot was real, and the Christian Front plotters did intend to carry out their bloody plans against the U.S. government.

Coughlin’s political impact extended beyond his most die-hard supporters as well. Recent research by University of Toronto economist Tianyi Wang has found that geographic areas where the stations carrying Coughlin’s broadcasts had the strongest signals recorded lower support than the mean for President Franklin Roosevelt in the 1936 election; were more likely to have branches of the nation’s most visible pro-Nazi group, the German American Bund; and less likely to buy war bonds after the U.S. entered the conflict. This latter finding is particularly significant given that Coughlin’s last radio broadcast was in May 1940, before FDR was elected to his unprecedented third term in office and more than a year before Pearl Harbor.

Powerful media voices like Coughlin helped foster an environment in 1930s America where antisemitism became a facet of the wider political discourse, though often confined to the margins. Chapters of the German American Bund sprung up across the country throughout the decade, and its summer camps hosted children and instilled them with the tenets of Nazism. Critically, the Bund and other antisemitic groups including the Silver Legion, presented themselves as patriotic, authentically American groups rather than adherents to a foreign ideology or government, despite being obvious Nazi emulators. And while neither group had a serious chance of winning a national election, it was impossible for Americans to simply ignore the organized antisemitism emerging around them.

This dark history of normalized antisemitism in both popular media and the fringe of American politics culminated in one of the most troubling displays of prejudice of the period—in this case from one of the nation’s most famous celebrities. In 1927, the young and handsome aviator Charles Lindbergh had become an overnight celebrity by completing the first solo flight across the Atlantic Ocean. Lindbergh returned to the United States as one of the most famous people in the world and, in the years to come, barnstormed the country in the Spirit of St. Louis, hounded by press attention wherever he went. In 1932, the kidnapping and death of his son established Lindbergh as a figure of sympathy in addition to admiration.

Less remembered, however, is that Lindbergh and his wife visited Nazi Germany several times starting in 1936. These missions were ostensibly undertaken as fact-finding or even spy missions on behalf of the U.S. government, but the fact that Lindbergh and his wife considered moving to Berlin in 1938 and the aviator received a medal from the Nazi government that year suggested that his interest in Germany went beyond aviation. The couple returned to the U.S. in April 1939 and after the outbreak of war in Europe, Lindbergh began making radio broadcasts calling for American neutrality. He later became a speaker for the America First Committee, the nation’s largest and most powerful non-interventionist group, with backing from business leaders and more than 800,000 members nationwide.

America Firsters came from all facets of society and included leaders from both major political parties. There is no evidence to suggest that a majority of America First members were antisemitic, but on the other hand, there were clear echoes of antisemitism among sections of its leadership. Most prominently of all, Lindbergh took to an America First stage in Des Moines, Iowa, on September 11, 1941, to deliver a speech denouncing the Roosevelt Administration’s supposed push to war, along with British efforts to draw the U.S. into the conflict. In addition to hitting his usual political themes, however, Lindbergh deviated to condemn “the Jewish” for allegedly supporting the attempt to bring the U.S. into the war. He went further, warning American Jews of “consequences” that might follow for them if the U.S. were to enter the war: “No person with a sense of the dignity of mankind can condone the persecution of the Jewish race in Germany,” he told the crowd. “But no person of honesty and vision can look on their pro-war policy here today without seeing the dangers involved in such a policy both for us and for them. Instead of agitating for war, the Jewish groups in this country should be opposing it in every possible way for they will be among the first to feel its consequences.” Tolerance, he went on, “is a virtue that depends upon peace and strength. History shows that it cannot survive war and devastations. A few far-sighted Jewish people realize this and stand opposed to intervention. But the majority still do not.”

Lindbergh’s sentiments were widely condemned by commentators, political leaders, and newspapers on both sides of the political spectrum. Yet despite the firestorm, Lindbergh himself believed he had done nothing wrong and never apologized for the remarks. Four months later, the America First Committee would disband after Pearl Harbor. The German American Bund and the Silver Legion would similarly cease to officially exist. Father Charles Coughlin had already been silenced by his superiors in the Catholic Church and would live out the rest of his days as a parish priest.

Ultimately, the organized antisemitism of the 1930s and 1940s was driven underground by wartime restrictions. And while antisemitism of course persisted after 1945, the postwar political establishment was wary of any echo from those tenuous days. As the RNC’s recent resolution notes, on the American right this initiative was led in part by William F. Buckley, founder and editor of the influential National Review. As conservative commentator Norman Podhoretz noted in 1992, Buckley recognized the uniquely corrosive force he believed antisemitism could have on conservatism, in part, he said, because his own father had been an antisemite. As a result, Buckley locked out writers he considered antisemitic from the pages of the National Review during the years of its greatest influence and later documented his views on the subject, to some controversy.

What, then, are the lessons of twentieth-century antisemitism for the present day? In some senses, the similarities between these periods are striking. In both, the emergence of new communications technology facilitated the spread of extremism to new audiences: in the 1930s it was the radio; today it is social media. It is sobering to imagine what Father Coughlin might have been able to do with Twitter. Similarly, in both periods we see the role of celebrity playing an outsized role in spreading extremist views to the wider public—and influencing politics. In 1941, Charles Lindbergh could command the attention of the nation’s press and share the stage with U.S. Senators. In 2022, Ye invites Nick Fuentes to dine with the former President of the United States, eliciting a response from elected officials and widespread media coverage. In both periods we see extremist groups organizing openly and using these major news events—and famous public figures — to further their own goals. It is too simplistic to argue that Ye is somehow a Charles Lindbergh of the 2020s—but it is important to consider the power of celebrity when it comes to spreading prejudicial views and, deliberately or not, giving prominence and credibility to extremist groups.

Lest we think the individuals who support these groups are unaware of these historical parallels, a quick perusal of the often-sympathetic comments accompanying a YouTube video of a Father Coughlin speech or a purported American fascist marching song should be enough to establish that, for today’s extremists, the past is a model and source to be drawn from and emulated. Similarly, those studying present-day extremism should look to the examples provided by the twentieth century to understand how antisemitism in particular can spread, take hold in a democratic society, and ultimately become a political force. Studying that history can also suggest how both the left and the right can combat antisemitism in their political ranks—and ultimately how a democratic society can defend itself against the corrosive power of prejudice.

Bradley W. Hart is the award-winning author of Hitler’s American Friends: The Third Reich’s Supporters in the United States.