Eugene Peterson and the Imperative of Biblical Literacy

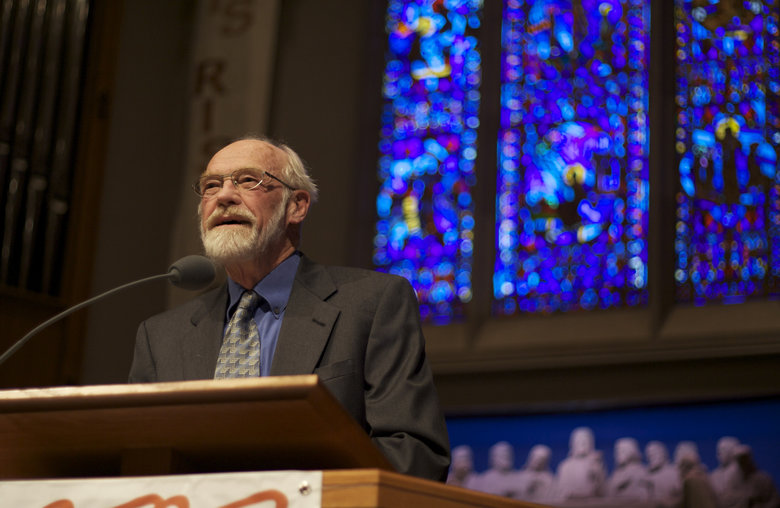

(clappstar/Flickr)

“Absolutely not!” I said. “You may not use that Bible in this class.”

“Aww, Doc, why can’t we use The Message? I really like it,” my student replied.

I sighed.

The Rev. Eugene Peterson died at the age of 85 in October. He had been a teacher of biblical Hebrew and Greek, and he founded and served as pastor of Christ Our King Presbyterian Church in Bel Air, Maryland. In addition, he authored numerous books, but he is probably best known as the beloved author of the best-selling book, The Message: The Bible in Contemporary Language. Initially published using only the New Testament in 1993, over time, Peterson released additional segments of books until he reached a full Protestant canon in 2002.

The Message bills itself as a “contemporary rendering of the Bible from the original languages, crafted to present is tone, rhythm, events, and ideas in everyday language.” In the King James Version of the Bible, Genesis 1:1-2 reads: “In the beginning, God created the heaven and the earth. And the earth was without form, and void; and darkness was upon the face of the deep. And the Spirit of God moved upon the face of the waters.” The New Revised Standard Version of the same text reads: “In the beginning when God created the heavens and the earth, the earth was a formless void and darkness covered the face of the deep, while a wind from God swept over the face of the waters.” In contrast, The Message reads: “First this: God created the Heavens and Earth—all you see, all you don’t see. Earth was a soup of nothingness, a bottomless emptiness, an inky blackness.”

Designed to be reader-friendly, it is enormously popular even among a crowded field of English-language Bible translations. Currently, The Message website lists a dozen different editions of The Message, including The Message//REMIX for youth and The Scribe Bible that provides room for journaling within its pages. Some conservative Christian scholars and organizations have endorsed and championed The Message for its simplicity and apparent clarity, while other scholars and pastors have ignored it or have dismissed and derided it as an eccentric paraphrase.

I confess that I have never been fond of Peterson’s The Message. While some of my Christian students, friends, and neighbors appreciated its contemporary language, as a biblical scholar, I simply had no use for it personally or in the classroom. Since Peterson’s recent death, I have reexamined and reflected on The Message. It has served to remind me of the high stakes involved in translation and the distance between academic biblical studies and biblical engagement outside of academia. For me, revisiting The Message has prompted a renewed conviction regarding the importance of fostering biblical literacy.

Content knowledge of the Bible is one element of biblical literacy. Certainly, understanding biblical content is important due to the Bible’s historical and ongoing cultural relevance. Religion professor Timothy Beal’s Biblical Literacy: The Essential Bible Stories Everyone Needs to Know supports this type of effort by identifying key passages and providing essential background on characters, events, and texts that are frequently quoted or referenced in Western literature and culture. I teach religion courses at a public university and have students from diverse backgrounds, but even among those who are from traditions that use biblical texts, I see a lack of basic content knowledge. For example, in a recent “Introduction to the Bible” course, my students did not recognize the biblical allusion in President Obama’s “My Brother’s Keeper” project. In the story of Cain and Abel in Genesis 4, after Cain kills Abel, God asks, “Where is your brother Abel?” Cain responds, “I do not know; am I my brother’s keeper?” The Obama initiative’s use suggests that unlike Cain and Abel, brothers should indeed be responsible for one another. When we later read the story of Cain and Abel in class, my students were shocked and questioned whether invoking a text about murder was appropriate for a youth initiative. As the semester progressed, learning more about biblical texts helped students to become more confident in recognizing allusions and in examining their uses.

While content knowledge is important, biblical literacy also requires a greater degree of understanding regarding translation itself a form of interpretation. It is not a mechanical construction of a one-to-one, beginners’ vocabulary list, but a complex process that involves numerous, deliberate choices. Whether it’s Peterson’s work as an individual or that of a multi-year, scholarly translation committee, translation is not neutral—it’s a political act in that it is affected by our interests and because it has real-world consequences. Yet, I find that many students do not think of English-language Bibles as translations. Often, they imagine Jesus, Moses, and even God as native English speakers. I bring to class a Hebrew Tanakh, a Greek New Testament, and other texts. Then, we look at different translations and their particular attributes. Acknowledging that translators are not neutral but engaged in creative work helps to generate a conversation regarding their notions of what constitutes a “real” Bible.

In the preface to The Message, Peterson explains that his aim was not to supplant study Bibles but to facilitate interest in reading biblical texts by making it more accessible. He notes that while serving as a pastor, he found that many of his congregants were not reading their Bibles. This observation is supported by research from the Pew Research Center. According to their 2014 Religious Landscape Study, among Christians, only 42 percent agreed that reading the Bible or other religious material was an essential part of being a Christian. Of mainline Protestants, only 30 percent read Scripture outside of religious services at least once a week.

While Peterson’s work may make biblical texts more recognizable and relatable for some, as an academic, I want biblical texts to be more alien and unfamiliar. That is, I want readers to understand that this is ancient literature that is written, compiled, and edited over time. An awareness of translation issues as well as the lengthy transmission and canonization process helps readers to understand the complexities in producing this anthology called the Bible. The Society of Biblical Literature’s online project, Bible Odyssey, provides an example of this type of public scholarship in religion. Scholars share their expertise and contribute to increasing biblical literacy by writing brief articles on topics related to biblical studies.

Like Peterson, I want people to read biblical texts, but more importantly I want people to investigate what is at stake in particular readings. Moving beyond content, it asks deeper questions. What constitutes authority? What is an authoritative text? Who is an authorized interpreter? What is “biblical”? With greater biblical literacy, one can recognize the need for and access information about biblical texts. Also, one can better understand how texts are functioning whether being deployed by a politician justifying a policy or by a clergyperson calling for community action.

Certainly, many of my colleagues in biblical studies and related fields are discussing these issues within their classrooms, and others are sharing their work in interfaith community groups and in essays and op-eds in various media outlets. Some clergy and other religious leaders make use of and share biblical scholarship with their congregants. Also, writers and journalists on the religion beat contribute to and disseminate public scholarship on religion. Efforts by the Pew Research Center, the Luce Foundation, the Wabash Center for Teaching and Learning in Theology and Religion, and others facilitate and contribute to public scholarship in religion and theology. And yet, there is room for more.

In an era of “fake news” claims, we can acknowledge the importance of improving media and information literacy. Also, we can agree that it is important for all of us to learn and improve our skills in determining what is inaccurate or misleading information in our news feed and why it is being used. Given the weaponization of biblical texts within the public sphere, I am encouraging similar efforts related to biblical texts in order to assist readers in having more of the tools needed to analyze and adjudicate claims. In Acts of the Apostles, Philip asks the Ethiopian eunuch, “Do you understand what you are reading?” He responds, “How can I, unless someone guides me?” I encourage biblical scholars and others to consider how they can contribute to that much-needed guidance. While I may question Eugene Peterson’s translations in The Message, I understand his desire to make biblical texts come to life. I am grateful for his passion for teaching and for helping me to rekindle my own.

Nyasha Junior is an associate professor in the Department of Religion at Temple University in Philadelphia. Visit her website www.nyashajunior.com and follow her on Twitter @NyashaJunior.