By now, it’s no secret that a majority of political conservatives are deeply concerned that America’s colleges and universities have a liberalizing effect on students. In a recent survey by Pew Research, 73 percent of Republicans expressed concern about the direction of higher education (compared to 52 percent of Democrats), while 79 percent cited professors bringing their political views into the classroom as a major reason for their concern (compared to just 17 percent of Democrats). When asked if colleges leaned toward a particular viewpoint, 72 percent of Republicans agreed, and a majority of them considered this a major problem; a minority of Democrats agreed with these assertions.

Bolstering conservative skepticism about higher education are stories of conservative students feeling targeted for their views, hiding their politics to protect their grades, and sensing their freedom of speech is under attack. One recent survey of 1,500 students found that 37 percent of Republican students felt unsafe on campus because of their politics, compared to just 11 percent of students who identified as Democrats.

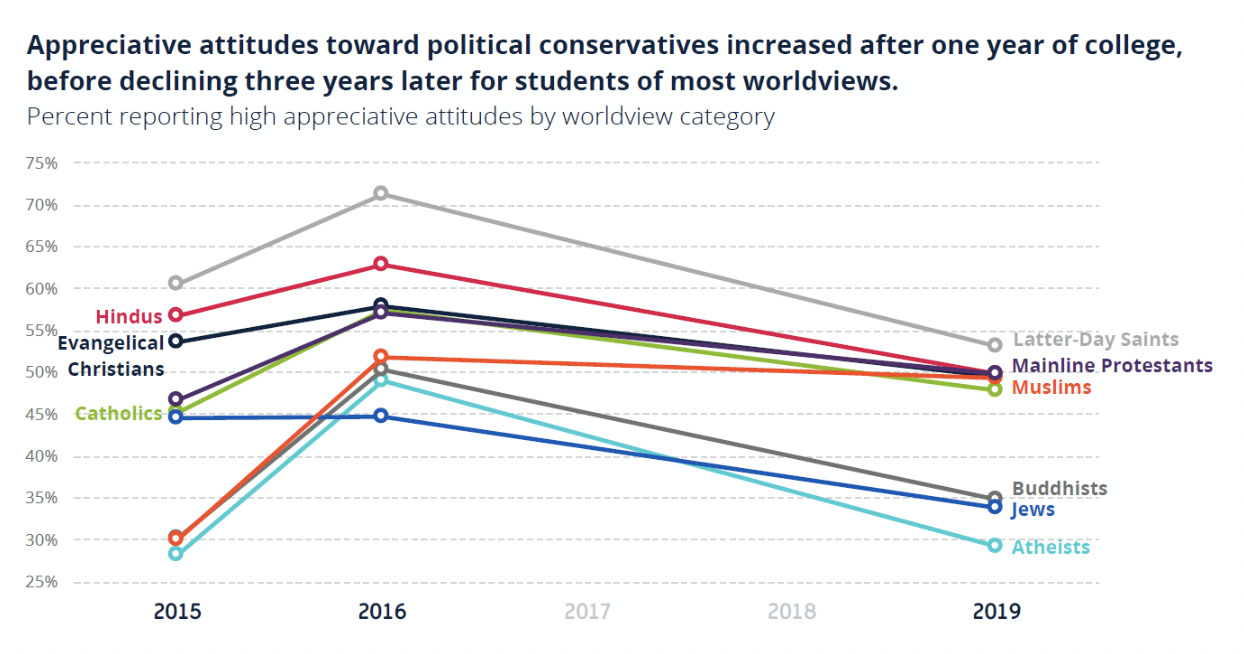

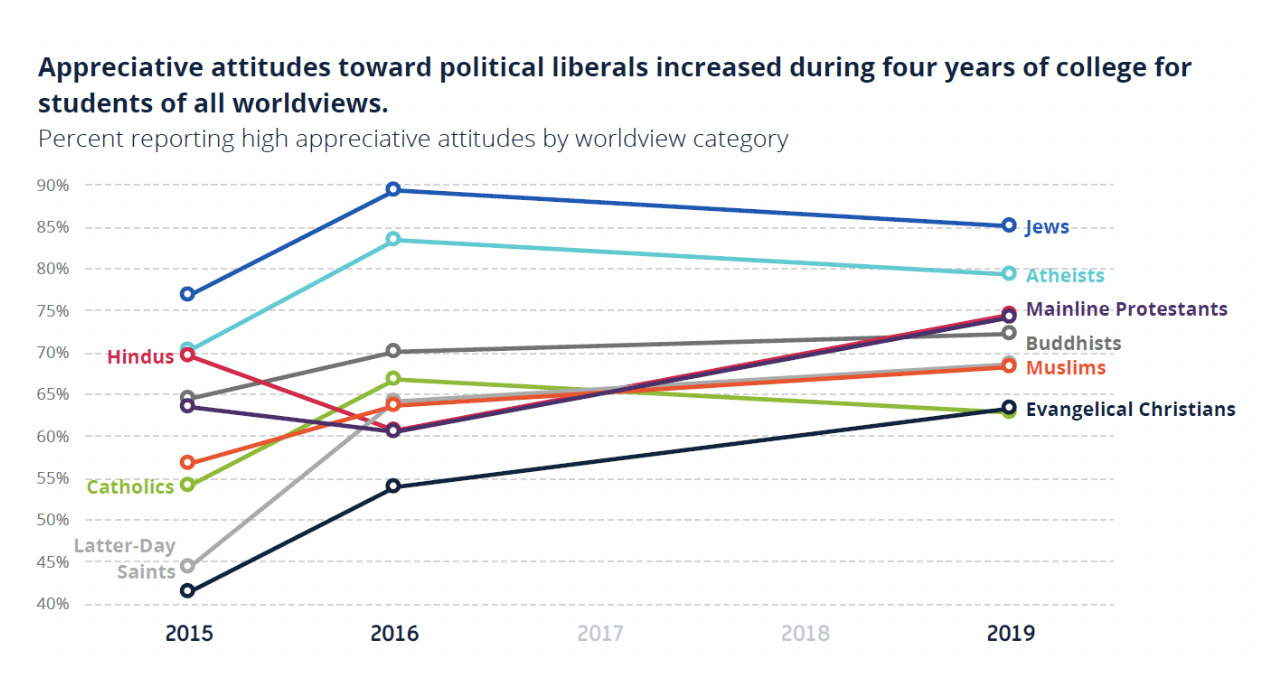

Given this backdrop, when our research team surveyed more than 7,000 college students at the end of their freshman year (early 2016) about their attitudes toward political conservatives, we had a feeling about what we might find. We were surprised, however, that overall student appreciation for liberals and conservatives grew at about the same rate during students’ first year in college. Nearly 48 percent of students had a more positive attitude toward political liberals, and nearly 50 percent had a more positive attitude toward political conservatives. We did not define “politically conservative” or “politically liberal,” but allowed students to define these terms for themselves.

Our study (IDEALS), performed in partnership with Interfaith Youth Core (IFYC), seeks to understand students’ experiences with worldview diversity and interfaith engagement across four years in college. (IFYC Founder Eboo Patel is on the National Advisory Board of the John C. Danforth Center on Religion and Politics, which publishes this journal.) This project includes examining how appreciative students are of diverse groups in society. IDEALS measures “appreciative attitudes” by asking to what level students agree with the following statements with regard to a particular worldview group:

- In general, people in this group make positive contributions to society.

- In general, individuals in this group are ethical people.

- I have things in common with people in this group.

- In general, I have a positive attitude toward people in this group.

Students who “somewhat” or “strongly” agree with these statements, taken together, are considered to be highly appreciative of a certain worldview group.

Four years after our initial polling, we surveyed some of the same students about their appreciative attitudes at the end of their senior year. What we found was staggering. Across all faith groups, those early gains in student appreciation for political conservatives were nearly or totally erased. The one exception was Jewish students, whose appreciation for conservatives didn’t grow in their first year but nonetheless declined by their senior year.

In some cases, appreciation for conservatives dropped even lower than when students started college. This phenomenon occurred among Hindus as well as within two very surprising groups: Latter-day Saint (LDS) and evangelical students, who traditionally hold more conservative views on politics.

On the other side of the aisle, student appreciation for liberals increased by their senior year in college, though Jews, atheists, and Catholics saw slight dips in appreciation for liberals between the conclusion of their freshman year and their senior year. Overall, these shifts in student attitudes resulted in a nearly 30-percentage point gap in “high” appreciation of liberals (70 percent) and conservatives (42 percent) at the end of their senior year.

Why was there this shift? Notably, student’s first-year growth in appreciation for political conservatives occurred during the final year of Obama’s presidency, before declining considerably during Trump’s first term. Trump’s rise was accompanied by heightened political polarization and spikes in hate crimes against minorities—including religious-based hate crimes on college campuses—a phenomenon that many observers are calling “The Trump Effect.”

College students of all faiths seem to have taken notice, but especially Jewish students. Out of all of the worldview groups in the study, Jewish students saw the greatest drop in their appreciative attitudes toward political conservatives during college. This is likely because anti-Semitic incidents account for much of the recent growth of religious-based hate crimes on college campuses. Though Trump has attempted to court Jewish students, the work of IDEALS suggests that it is strongly unlikely that Jewish college students will support him in 2020.

Muslim students also experienced a rise in campus hate crimes, and began their freshman year with the second lowest appreciation for political conservatives. Only atheists were less appreciative. Interestingly, by their senior year, Muslim students had the greatest gains in their appreciation of political conservatives overall, and the drop between their freshman and senior year was the least of all groups in the study (just a 2 percent drop). In fact, by their senior year, Muslim students appreciated political conservatives as much as evangelical students did. Though Muslim students reported more appreciation for political liberals overall, they were not in the top five groups in terms of appreciation level. In light of Trump’s travel ban on Muslim countries and inflammatory tweets about Muslims, these findings from IDEALS deserve further exploration.

Though conservatives fear that higher education may be antithetical to their views, IDEALS found that students of all faiths in the class of 2019 were warming up to political conservatives at the end of their first year in college, which was during the final year of Obama’s presidency. Now, three years into Trump’s presidency, conservatives can only wonder what could have been.

The Trump effect is likely the primary contributor to the most polarized freshman class in half a century, which arrived just one year after IDEALS began surveying students; it is also likely a primary contributor to declining appreciation for political conservatives among students of all faiths (and no faith) during Trump’s stint in the Oval Office. This fact raises important questions: How much is higher education truly to blame when students become fonder of liberals (or less fond of conservatives) during the Trump years? At what point does the Trump effect deserve to share the blame? Furthermore, is it possible that colleges and universities are making sincere attempts to destabilize negative attitudes toward political conservatives, but the Trump effect is simply too powerful to overcome?

Nevertheless, it is incumbent upon colleges and universities to work toward alleviating political polarization on campus, which poses a threat to students’ sense of safety and belonging. Fortunately, in our research, we have also learned that enduring friendships across deep religious and political differences are an effective tool for reducing polarization in all forms, proving that relationships may be key to bringing people together—the ultimate means of trumping the Trump effect.

Matthew J. Mayhew is the William Ray and Marie Adamson Flesher Professor of Educational Administration at the Ohio State University.

Kevin Singer is a doctoral student in higher education at North Carolina State University.

Alyssa N. Rockenbach is Professor & Alumni Distinguished Graduate Professor of Higher Education at North Carolina State University.

Laura Dahl is an assistant professor of higher education at North Dakota State University.