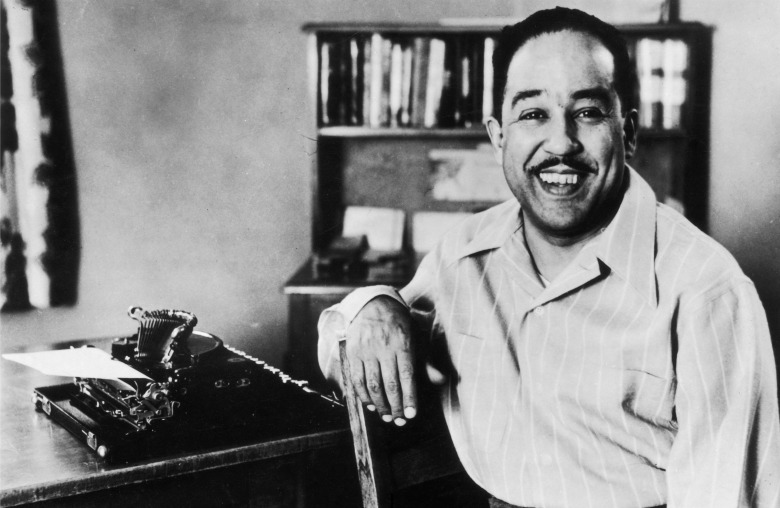

(Getty/Hulton Archive) Langston Hughes

Langston Hughes, the literary titan of the Harlem Renaissance, did not identify as a religious believer. And yet, Hughes wrote as much about religion as he did anything else, according to Wallace D. Best, who argues in his latest book that the religious dimensions of Hughes’s work have too often been dismissed or ignored. In Langston’s Salvation: American Religion and the Bard of Harlem, Best mines Hughes’s canon of poems, plays, novels, and commentary, exploring the ways in which the writer was a “thinker about religion,” even if he was not religious himself.

Best sat down to talk about the book with Josef Sorett, author of Spirit in the Dark: A Religious History of Racial Aesthetics, which explores African American religion and literature, including the work of Hughes. Sorett is an associate professor of religion and African American studies at Columbia University, where he also directs the Center on African American Religion, Sexual Politics and Social Justice. Best, a professor of religion and African American studies at Princeton University, is also the author of Passionately Human, No Less Divine: Religion and Culture in Black Chicago, 1915-1952. Their interview has been lightly edited and condensed.

Josef Sorett: Some might be surprised to see you, a historian of the Great Migration, move toward being a scholar of African American literature with this biographical study of Langston Hughes. Can you start by telling us how you got to this book on Hughes?

Wallace Best: This book in many ways is born from that research that I did in Chicago years ago, when I was working on Passionately Human as a dissertation, deep into the archives and into the issues of movement and migration and the way in which that transforms African American religious practices in Chicago and beyond. Langston Hughes’s name kept coming up. His name would come up in church documents, the papers of ministers and church workers. His name would come up in gospel music programs. I found him in unexpected places in my research on Chicago and that intrigued me.

My understanding of Langston Hughes was that he would be un-churched and unconcerned about churches and unconcerned about religion. I was thinking: Why would this atheist, who as one of his biographers would say was “secular to the bone,” show up in the documents on Harlem and Chicago’s world of religion and churches? He was there, from what I could tell, as an active participant. I knew once I finished the book on Chicago, I had to further explore this angle, and it began with that simple question: What is the relationship between Langston Hughes and American religion?

I thought it was a simple question, but it turned out to be an enormously complex, intricate, and textured question about religion, about literature, about Hughes, about church culture, about religious cultures more broadly—all of which, to my surprise, he was very interested in, and wrote quite a lot about. I returned to his own work—to his poetry in particular—with my encounter of him in those documents in mind to, in a sense, read him religiously. That is, to read him with the idea that he perhaps had something to say about religion. That’s how it started.

What I discovered is that he had quite a lot to say about religion. I argue in the book that Langston Hughes wrote as much about religion as he did about any other topic if we broaden our understanding of what religion actually is. And that’s when it got rich. Because what Hughes began to offer me in my exploration was this much more broad and expansive way to think about what constitutes religious writing. His poems, his plays, and his social commentary became available to me for religious analysis.

JS: One of the phrases you gravitate to is this idea of Hughes not necessarily as religious but as a “thinker about religion.” You begin with his failed salvation experience. Tell me more about his failed salvation experience and how that story definitively shapes his thinking.

WB: Hughes talked about his life this way: He said there were three events in his life that were absolutely foundational, and these events shaped his thinking about love, about life, about relationships, and most particularly, I think, about religion. One of those events was when he discovered as a young teenager that he hated his father. He said that very clearly, he hated his father—for reasons that he went on to explain. The other event was when, in 1930, he was rejected by his patron, Charlotte Mason, who had been supporting him and his art. Now, the literature on Hughes picks up on those two, but they forget one, and Hughes talked as much about this one as he did those two. And that was when he was “going on twelve years old,” as he puts it, that he had a failed salvation experience in Lawrence, Kansas. It absolutely shaped his thinking about religion. And I argue that everything that he wrote about religion, in some way, reflects back to that failed salvation experience. It was a type of spiritual trauma, in one way. But I think what it also did was liberate him to talk and to think about religion, and specifically about salvation, in different ways.

Hughes had a failed salvation experience, but it by no means suggests that he didn’t find types of salvation throughout his life. What I suggest is that salvation becomes a bit of an obsession for him, and he wrote quite a lot about the topic of redemption—how one is redeemed, how one is saved. Hughes had that traumatic night when he failed to see Jesus, but it didn’t cut him off from the pursuit to understand what it means to be saved, what religion is and its function in daily life—on a personal level and on a communal level.

Just because Hughes cannot—and he does not—explicitly state or position himself as a religious believer, one cannot, then, discount his works on religion. He wasn’t a believer, and certainly not a believer in that conventional way that we have come to understand believers. Rather than a religious thinker, he is a thinker about religion.

JS: You seem to be bringing together the fields of literary history and religious history—which is to say that Hughes may have been at the salon, but he was also at churches. Were you writing more to historians to think differently about this literary figure or were you writing more to scholars of religion?

WB: I think I coined a term here when I called it a “historical analysis of religious literature” or “religious and historical analysis of literature.” I knew from the start that I was writing in between fields. The reception of the book and how people find their way to it has been curious. But even on the back of the book, it’s designated as in the field of literature. I had fought for it to be in the field of history and religion, but I think the editors, in the end, understood that the way to get the most people to this book was by classifying it as literature.

JS: They were trying to appeal to Hughes’s fans.

WB: Hughes’s fans would get there first, right? The reason I wanted to characterize it as religion is because in some ways that was my target. Because really what I wanted to do was say to my scholarly religious folks, “Look, might we sit down and think about new ways to do what we do?” I mean it was just that simple. I wanted to revive a type of conversation about the usefulness of African American literature for religious analysis. And here’s the key. I wanted to spread that net out widely and to include the voices of those who spoke not just from the position of belief. Because I think African American religious history has primarily has been written from the perspective of belief and believers. What I wanted to do was to include the voices of the skeptics, the doubtful, the uncertain because I think those folks have made contributions that have been unacknowledged in the way we even construct African American religion.

JS: We could locate that within the rise—in scholarship at least—in the interest of secularism. That’s almost an implausible idea within African American religion—the idea of a black unbeliever. Where is the space for black unbelievers or folks who believe differently?

WB: Can’t we acknowledge that they have already had an impact on the construction of African American religion? I think of James Weldon Johnson, who wrote in his autobiography Along This Way that he was agnostic. What he does is articulate his uncertainty about the existence of God, which did not prevent him from writing God’s Trombones.

JS: Which creates a canon of black sermons, right?

WB: It didn’t prevent him from joining with his brother to write “Lift Every Voice and Sing.” And so, voices of the doubtful, the skeptic, even the agnostics, and perhaps even the atheists have already contributed to the structures and the discourses and the forms of African American religious histories and traditions. They’re already there. So what happens when we return to them and look at them as an alternative source of spiritual authority? What happens when we take Hughes’s thoughts about religion seriously? Let’s not dismiss them just because he himself was not religious, because then that becomes a judgment about the scholar.

JS: One of the distinctions that you make within the book is that Hughes is less interested in dogma that he is in drama. What does it mean then to think of the dance and the shout or to think about his gospel plays? How does that force us to think about religion differently? Is that a different way of thinking about black religion?

WB: Possibly. Hughes wrote Tambourines to Glory and Black Nativity and he wrote the short story “Blessed Assurance” and on and on. Those works are deeply informed by his own encounter with black faith. What does it mean for someone who suggests him or herself to be a non-believer to write something that can strike the same chord religiously? Hughes didn’t misrepresent the tradition in any way. One would expect that if he is not a believer, perhaps he would strike the wrong notes in his depiction of this tradition. He did not do that, and I think that that’s informative for us—that the traditions of African American religions are not the exclusive province of those people who actually practice it. I haven’t worked all of that out. I still find it interesting that Hughes struck all the right chords. When you read some of that religious poetry from the 1920s, it’s palpable—you can just feel the presence of a black folk revival. In other words, he wrote it well.

JS: It seemed to capture the spirit of it.

WB: He captured it. And what does that mean? I think we have to take that seriously. One of the things I’m trying to get us to do, ironically enough, is to pull ourselves out of the position of making judgments about sincerity or who’s inside and who’s outside. Let’s take Hughes for what he offers us, right? Let’s take what he offers us and recognize its value on its own terms. For me, that creates all kinds of space to think openly and creatively about the traditions themselves.

I gave a talk a couple of months ago—and I was meaning to be provocative, but I think I was preaching to the choir. I said, “I’m not trying to get people to close their Bibles. I’m just trying to get them to also open up The Color Purple.”

JS: Other forces are often considered sacred within the context of black Christian worship, even if not named as such.

WB: Exactly. That’s what I’m saying: Let’s read the Bible, but let’s not forget The Color Purple, let’s not forget Tambourines to Glory and on and on and on it goes. The literature. If we want to think in new ways about African American religion and religious history, the sources to do that have been with us all along.

JS: If Hughes is not religious, per se, or a religious thinker, you said that art for him becomes, in some ways, salvation. For me, that resonated with the popular discourse of someone who is spiritual but not religious. The idea of a spiritual seeker does seem similar to what you’re suggesting in Hughes’s pursuit of a sense of self, of an identity, of a community through an artistic vocation. Can you say more about that, even if you don’t want to claim that he is a spiritual seeker?

WB: It’s paradoxical in many ways because I didn’t want to “name” or label him. I wanted to just pay attention to what he was doing as much as what he was saying, without sort of giving it, you know, a name or an identity. I did that because one of things that I noted in the book and in my research was that Hughes was suspicious, perhaps even allergic, to notions of identity. We haven’t talked about sexuality, but one of the reasons why we are unclear about his sexuality is because he wants us to be unclear about his sexuality. And so, every time I go to an exhibit on black writers and sexuality, Hughes is always on the board with the gay writers. He wouldn’t like that—not because he was homophobic, but he wouldn’t like that because that was an identity that was given to him. He never told anybody that’s who he was, right? That’s the same thing with religion, right? He never said he was religious, right? He never said, “This is my identity, I belong to this church.” In fact, he was saying the opposite: “I belong to no political party, and I belong to no church.” He said that often. This made him hard to write about. How do you write about someone who’s resisting identity and all and is paradoxical in his presentation at all times?

JS: Religion has showed up all over the contemporary landscape, including in debates around sexuality. Complicating about how we think about religion also complicates how we think about sexuality. Is there more you want to say about that?

WB: I’ll put it this way. Early on, when people found out that I was going to do this book on Langston Hughes, several people wanted me to find the smoking gun. Was Langston Hughes gay? I’ll never forget the first talk that I gave on this and the first question was about his sexuality. There’s something about Langston Hughes—and I think I know what that something is—that provokes that question. Was Hughes gay? I would’ve been happy to have found the smoking gun. I did not find that smoking gun.

What I found was something that I thought was much more interesting. I found someone who was very keen on his own self-fashioning around identities. The only identity that Hughes consistently asserted in his writing and in his presentation was that of a Negro artist. When it came to religion, as well as when it came to politics. Most people think he was a Communist, but he declared from the 1930s until his death in the late 1960s that he was not a Communist. He had never joined the Communist Party; he was not a joiner in that way. He went to St. Phillips in Harlem so much that they thought he was a member there. He was not a member there. He said, “I am not a member of any church or any political party.” What he was doing there was freeing himself from being understood in particular ways. This careful self-fashioning of who he was and who he wasn’t. Now was he gay? Maybe. But when you look at his life, the reason why I’ve resisted calling him gay is not only that Hughes didn’t declare an identity when it came to his sexuality. It was also the fact that when you look at his life, he had a much more complex relationship to sexuality itself. He had relationships with women. He talked about one encounter that he had with a man. He was the object of attraction for other men, and he was aware of that. He had a relationship with one of his high school buddies. I’ve read those letters—they are charming, they are wonderful, they are romantic—there must have been something sexual between the two. And so what you find is a spectrum there more than anything. So to say that he was gay, or to say that he was religious, might misrepresent the fullness of that aspect of his life. To say he was gay or to say he was religious wouldn’t open things up, it would actually close off things. And I think that is what he would have rejected.

JS: Rather than closing off, you turn to Hughes’s gesture to open up. What new possibilities do you hope this work will engender in the fields of religion and politics and American culture. What new kind of work do you hope to open up?

WB: Part of it has to do with our own approach. I think there has to be a change in what we think is possible in this work. One of the things I think we need to do is rethink the sources that are available to us. I think we have to bring in many more perspectives. That’s why I say the book is and isn’t about Hughes. Hughes is a lens that I’m using to point to possibilities about how we think about the structures of the tradition. We need to return to literature, we need to turn to voices of the doubtful, of the skeptics, the uncertain. I think they have value. I think they jettison our impulses to bifurcate the secular and the sacred, even in how we research and write.

I want to create a space for people that, in my view, have always been among us, trying to inform what it is that we think about and how to write about this tradition. If we do that, the possibilities are endless for how we narrate the tradition. In other words, the tradition is a lot richer than we’ve given it credit for because we’ve only listened to certain voices and because we’ve only listened to those voices in certain ways. If we free ourselves to really think about the dynamism of African American religion and religious history, the possibilities of how we write are endless. Our work will bridge many more disciplines. The field of religious studies is inherently interdisciplinary. Well, then, let’s do that. Let’s let our work truly represent that.