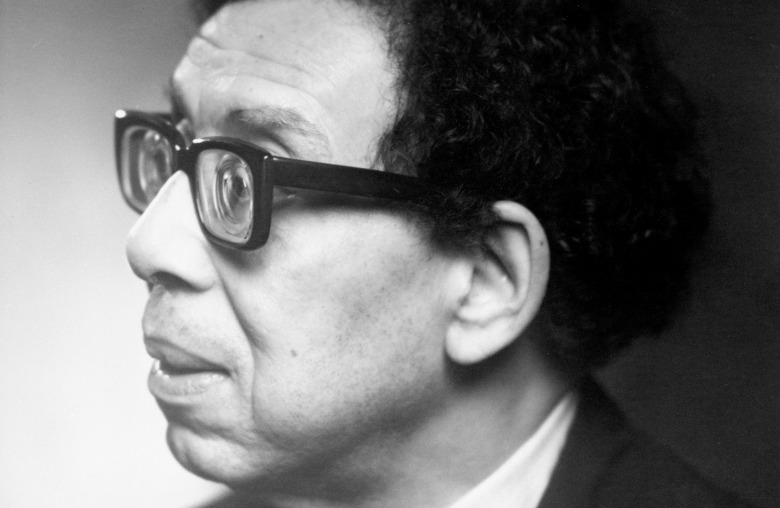

(Getty/Corbis/Oscar White)

In February, the new administration kicked off its first celebration of Black History Month with a discussion between the president and several of his African American diversity advisors. If unsurprising, much ado has been made about certain episodes in their exchange. Most notably, Trump himself outlined a litany of African American heroes in such a way that confused the boundaries between past and present. In a nod to the significance of Frederick Douglass, the famous nineteenth-century abolitionist, author, and orator, Trump casually remarked, “Douglass is an example of somebody who’s done an amazing job and is being recognized more and more, I notice.” Whether his error was grammatical or historical, the slippage in Trump’s uninformed and empty acknowledgement of Douglass—whose legacy is steeped in opposition to white supremacy and in support of human equality—led to a Twitter-storm highlighting the administration’s ineptitude, once again, on broader matters of fact and truth alike. More substantively, Trump’s Frederick Douglass-gaffe calls attention to an impoverished vision of diversity and inclusion, as it relates to matters of domestic and international policy—but also against a backdrop of a persisting threat from the White House to eliminate funding for the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Endowment for the Humanities, both of which help to make work in the arts and humanities possible.

Two days later, in one effort to correct the record and more appropriately acknowledge Douglass, the Poetry Foundation featured as its poem of the day a selection by the United States’ first black poet laureate, Robert Hayden. First published in his 1962 book, A Ballad of Remembrance, Hayden wrote a poem that considered Douglass’s significant legacy and his unrealized vision for human freedom. Naming it simply, “Frederick Douglass,” he penned the following:

When it is finally ours, this freedom, this liberty, this beautiful

and terrible thing, needful to man as air,

usable as earth; when it belongs at last to all,

when it is truly instinct, brain matter, diastole, systole,

reflex action; when it is finally won; when it is more

than the gaudy mumbo jumbo of politicians:

this man, this Douglass, this former slave, this Negro

beaten to his knees, exiled, visioning a world

where none is lonely, none hunted, alien,

this man, superb in love and logic, this man

shall be remembered. Oh, not with statues’ rhetoric,

not with legends and poems and wreaths of bronze alone,

but with the lives grown out of his life, the lives

fleshing his dream of the beautiful, needful thing.

Hayden lionized Douglass as someone “superb in love and logic,” who pushed past the “mumbo jumbo” of political calculations in favor of unqualified freedom for all. At the same time, much like Black History Month is intended to do, this poetic act of remembrance also seemed to renew the writer’s gaze on “freedom, this liberty, this beautiful and terrible thing” in the early years of the tumultuous 1960s. Here Hayden’s own utopian vision in verse was inspired by the example of Frederick Douglass’s life. Yet this one poem was also emblematic of Hayden’s larger artistic vocation, which fused religious and literary themes and drew lessons from the wells of history.

While African American history, in particular, was a valuable resource across his literary career, Robert Hayden’s poetry also reflected the constraints and possibilities of his own biography, beliefs, and historical moment. More often than not, his aesthetic did not lend itself to a neat alignment with the orthodox race politics or religious dogmas of the times in which he lived. Born in 1913, Hayden grew up in Detroit, Michigan. As a young man, he worked for Detroit’s WPA Federal Writers Project during the 1930s, and then honed his craft further at the University of Michigan in the early 1940s under the tutelage of W. H. Auden. Also during the 1940s, Hayden and his wife Erma embraced the teaching of the Persian prophet Baha’u’llah and joined the American Baha’i community. Thus, he wrote both as a black American and, for many years, as a member of the American Baha’i community. Later in his career Hayden would confess to struggling with his beliefs. Yet his poetry drew deeply on the Baha’i faith, a religious tradition that continues to be considered non-traditional and which marked him as marginal in black literary circles for much of his career. Even still, so much of Robert Hayden’s poetry plumbed the particulars of his own “black” experience. Rather than an elision of race politics, Hayden’s refusal of such modifiers as “negro” or “black” was born, at least in part, out of religious commitment. As he eventually explained in an interview with the editor Richard Layman, “I believe in the essential oneness of all people and I believe in the basic unity of all religions. I don’t believe that races are important. … These are all Bahá’í points of view, and my work grows out of this vision.” For Baha’i adherents like Hayden, relinquishing racial identification was part of a process of achieving spiritual maturity.

While the poet pursued a distinctive path to artistic and religious maturity, the Baha’i faith itself experienced a coming of age, of sorts, during the span of the Robert Hayden’s life. In fact, the religion received a broad hearing in the United States in the decades that preceded Hayden’s conversion. The Baha’i leader, Abdul Baha, delivered a series of public talks across the U.S. in 1912 on key Baha’i tenets, such as “The Oneness of Mankind,” which was later codified in The Promulgation of Universal Peace. Shortly before World War I, Abdul Baha had addressed a wide range of audiences in the United States, including at the NAACP, Howard University, and the Bethel Literary Society at the historic Metropolitan African Methodist Episcopal Church in Washington, D.C. Similar talks were given in homes and at civic organizations, synagogues, theosophical societies, and liberal churches of diverse denominational ties. Robert Hayden, who grew up attending a Baptist church, was one of many Americans—from diverse racial and religious backgrounds—with whom the Baha’i message of racial equality and religious unity resonated deeply.

Additionally, during the mid-1940s, for Hayden the Baha’i emphasis on religious and racial unity paired well with Auden’s push for him to move beyond the particulars of racial themes. Although it was not precisely Protestant, Hayden’s poetry subtly wove together race and religion at a moment in which these discourses converged to help underwrite a burgeoning human rights discourse. In 1948, the same year that the General Assembly of United Nations adopted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Hayden’s literary and religious influences came together in a pronounced fashion. That year, along with poet Myron O’Higgins, he set out to launch a new series of poetry pamphlets that they titled Counterpoise. Their first publication, The Lion and the Archer, was covered in The New York Times, where the critic Selden Rodman described the 20-page collection of poems as, “the entering wedge in the ‘emancipation’ of Negro poetry in America.” Though their collaboration only produced this one pamphlet—and O’Higgins never achieved acclaim comparable with Hayden—the launch of the Counterpoise Series was viewed as a major development in American letters. Indeed, the short string of verses that served to introduce the series, and which doubled as a subscription flyer, has been described as a “manifesto” for a new generation of black writers. In light of Robert Hayden’s then-recent embrace of Baha’i teachings, the Counterpoise Series announcement can be read as both an artist’s credo and a confession of faith.

Though the text made no direct mention of race matters, in it Robert Hayden addressed several audiences at once, challenging orthodoxies on both sides of the color line. In ways that anticipated his confrontation with Black Arts poets during the 1960s, the Counterpoise Series rejected any particular status or category for writers who were also considered racial minorities. While the richness of the African American experience offered unique resources, Hayden’s Counterpoise introduction explained that he would not allow race politics “to limit and restrict creative expression,” nor would he provide the sort of racial propaganda often called for by race leaders. Instead, irrespective of artistic medium (i.e., “writing, music and the graphic arts”), openness to “the experimental and the unconventional” was paramount.

Though his artistic vision squared well with an international vision of human rights that was then emerging in opposition to European fascism and U.S. segregation, Hayden nonetheless declared his opposition to the idea that work by black poets was received, “as the custom is, entirely in the light of sociology and politics.” Additionally, he contended that uncritical celebrations of underdeveloped work by black artists— by a liberal, largely white art world— were equally undesirable. He explained further in the Counterpoise introduction that neither “a conscience to salve” nor a political “axe to grind” were due cause for anybody to be “overpraised.” To be clear, Hayden was not suggesting that mainstream presses were indiscriminately underwriting black mediocrity. After all, he would not receive a contract from a commercial publishing house for another two decades. However, those who presided over publication opportunities—“editors, reviewers, anthologists”—were not to be granted the power of life and death over an artist’s vision. Black leaders and the (presumably white) literary establishment were both served notice. The poet would not be bought, either by affirmation or exclusion.

Structured something like a hybrid of poetry and prose, yet not quite conforming to either genre, the introduction to the Counterpoise Series was devoid of any definitive beginnings or endings. Its lack of any periods or capitalized letters revealed a modernist emphasis on experimentation in form. Its absence of punctuation aside, the piece perhaps most resembled a religious litany. It read as a call to action to be recited by a congregation of believers. Indeed, the word “believe” appeared three times: once early on to affirm “experimentation” and then again in each of the manifesto’s last two lines. Here Hayden’s religious ambitions were subtly unveiled. As literary critic Brian Conniff has noted, by the time Hayden arrived at the University of Michigan, Auden had begun to think of poetry as a “religious vocation.” Yet Hayden asserted his own spiritual identity by invoking the most fundamental Baha’i principle. Bringing the Counterpoise introduction to a conclusion, he declared, “We believe in the oneness of mankind and the importance of the arts in the struggle for peace and unity”—an obvious invocation and adaptation of the Baha’i belief in “The Oneness of Mankind.”

Robert Hayden’s long-held position on the outskirts of the African American canon was a by-product, at least in part, of the fact that his aesthetic was so deeply informed by the Baha’i faith. Although his poetry drew heavily on the Bible, his version of Afro-modernism was post-Protestant—neither a disavowal nor a declaration of Christian faith. It was ultra-modern, to the point of misrecognition. Because of his refusal to neatly align himself with racial orthodoxies, he was often relegated to the margins of black cultural life even as he was welcomed into the annals of American poetry. Before the end of his distinguished career, he would be appointed the first poet laureate of Senegal and the first black poet laureate of the United States (an honor then titled “Consultant to the Library of Congress”), serving from 1976 until 1978—his term ending just two years before his death.

Robert Hayden’s aesthetic was by no means a political panacea, never mind a policy remedy, for the social problems of his day. By the time he officially exchanged his black Baptist upbringing for membership in the American Baha’i community, and penned the Counterpoise introduction, Hayden could be counted among a significant group of Americans who converted to the novel religious tradition. And on the heels of World War II such ideas sounded anew in both religious and political registers. Statements endorsing the “oneness of mankind” had taken on new institutional life with the formation of the United Nations in 1945 and four years later, in 1949, with the signing of North Atlantic Treaty that gave birth to NATO. Indeed, as historian and legal scholar Samuel Moyn has detailed, the burgeoning discourse on human rights was one secularizing trajectory that Christian theology followed across the twentieth century.

By no means isolated from this religious history of human rights, Hayden’s Baha’i beliefs contributed to a literary vision—versed in black history and based in formal experimentalism at once—that paved a parallel afterlife for Protestantism. Much in the same way that his poetry was enlisted as a corrective to recent Black History Month commentary, Hayden’s Counterpoise “manifesto” provides a compelling counter to recent efforts by Trump’s White House to close borders, reinscribe old nationalisms, and restrict the boundaries of human community. Moreover, in its fusion of history and poetry, Hayden’s “Frederick Douglass” reminds us all of the important work of the arts and humanities in lifting up and celebrating “this freedom, this liberty, this beautiful and terrible thing” in the face of “the gaudy mumbo jumbo of politicians.” And, thus, much like Frederick Douglass’s work and life, Robert Hayden’s religious and literary vision is no less relevant today.

Josef Sorett is an associate professor of religion and African-American Studies at Columbia University, where he directs the Center on African-American Religion, Sexual Politics and Social Justice. He is the author of Spirit in the Dark: A Religious History of Racial Aesthetics, from which this excerpt was adapted.