Donald Trump’s proposal to ban all Muslims from entering the United States, possibly including U.S. citizens, produced immediate, and well deserved, condemnation from figures across the political spectrum. President Obama and Republican National Committee Chair Reince Priebus both stated objections to the plan because it contradicted “American values.” But while Trump’s proposal may be antithetical to the values we want to hold dear as Americans, it is unfortunately not always antithetical to our practice, speech, or history.

While many pundits have looked to former regimes in Germany or Italy to explain the dangers they perceive Trump to embody, we need to understand him and his following as an American phenomenon. Trump and his Islamophobic remarks draw on a long history of American exclusion that takes place at the intersection of race, religion, and nation of origin. And Trump’s following is the result of intentional interest-group strategies pursued over the last five decades.

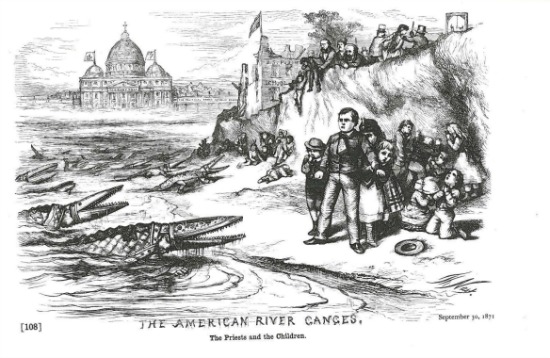

The United States has a long nativist tradition, which is now focused on Muslim communities. John Higham, in the canonical book Strangers in the Land, wrote that nativism is “an intense opposition to an internal minority on the ground of its foreign (i.e. ‘un-American’) connections.” This opposition can have a wide range of targets in “response to the changing character of the minority irritants and the shifting conditions of the day; but through each separate hostility runs the connecting, energizing force of modern nationalism.” The durable American nativist tradition has an additional common feature: a racial religious othering. Throughout history we see religious differences being blended with racial differences; groups of people perceived to be sharing a religion are characterized as having innate immutable differences that threaten the native citizens or the nation as a whole.

Debates in the late nineteenth century over Chinese immigration display a blending of concerns about loyalty with nation of origin, religion, and race. Senators declared that the Chinese were a “Pagan race” and threatened to establish their Pagan institutions in America. The Chinese, because of their perceived differences at the intersection of race and religion, were thought to not only be unable to assimilate but also to be a fundamental danger to America. This misguided fear led to increased scrutiny and eventually attempts to deny entry to the United States for most Chinese.

Nativist responses to new immigrants from southern and eastern Europe in the early twentieth century were also centered at the intersection of race and religion. Advocates who opposed immigration argued that these newcomers from sending areas in Europe, including Italian and Irish Catholics as well as eastern European Jews, threatened to overwhelm the U.S., and to damage the racial and religious character (read: white, Anglo-Saxon Protestant) of the country. The progressive-era drive to use science to address social problems generated arguments grounded in eugenics.. Nativist forces talked about the threat of “race suicide” that would result from not restricting the immigration of, for example, the fecund Irish immigrants. One policy proposal they generated may sound familiar: first, a pause in immigration; then allow the country to assimilate the current immigrants; lastly, gather more information about the effects of immigration. When more information was in fact gathered, the pause became standing legislation and the 1924 national origin quotas were put into effect, establishing specific immigration allotments for each country—all in an attempt to preserve a false national identity that was white and Protestant.

Trump proponents are once again asking for a “pause” in immigration so that the country can evaluate how to handle racial and religious minorities. While many are taken aback by the jarring nature of targeting of an entire religion as potentially dangerous, the leading candidate for the GOP presidential nomination has been able to voice such a stance and retain support (and even gain new support in some places). Trump, always conscious of the polls, knew that he would have a base of support for such an announcement.

More recent American political history also paved the way for Trump’s popularity. The Republican Party’s 1960s “Southern strategy” attempted to mobilize southern whites, discontented over race, to join the Republican Party. This conscious, political maneuver drew on the racial and religious norms undergirding Southern society. Racial hierarchy in the South had long been defended as divinely ordained. And the nostalgia for the Confederacy could not be removed from the Christian heritage of the South, evidenced most clearly in the religious symbolism embedded in the “Southern Cross,” or the Confederate flag. Politicians developed coded language and campaign outreach that would generate votes from those concerned primarily about defending a white Christian American identity.

The Southern strategy was one of the forces that set the stage for the rise of the Christian Right in the 1980s. As the movement grew, the Christian Coalition, one of its central organizational forces, attempted to reach out to new groups. To expand their base they pursued non-Protestants and non-whites, engaging in campaigns to include Black and Latino religious citizens as well as conservative Catholics and Jews. In order to create this broader alliance, the organization depicted atheists as well as non-targeted religions as threatening to the United States. Muslims served as a central foil to transform the narrative of the white American Christian heritage into an American “Judeo-Christian” tradition. For example, a 1991 Christian Coalition publication noted with alarm that for the first time in more than 200 years a Muslim prayer had been used to open Congress. Islam was depicted as posing a clear danger to the American tradition.

While the Christian Right as an organized movement has weakened considerably, the legacy lives in the tropes crafted and the political base that developed. After the terror attacks in 2001, these anti-Muslim narratives became incorporated in a larger set of public debates. The criminalization of the immigrant turned to include Muslims in its focus. Terror babies joined anchor babies as threats to the nation and our national character. Trump draws on both these strands in his rhetoric. Much of his support, as polling data from the Public Religion Research Institute shows, can be attributed directly to his hardline approach on immigration.

In the furor over Trump’s statements, politicians and scholars have suggested that banning Muslims from entry is “anathema to the traditions of the nation.” Some have argued that such a ban amounts to an unconstitutional religious test that would have repelled the Founding Fathers and their commitment to religious freedom. Yet these claims are not an accurate reflection of the American experience, which has in the past included religious tests for public offices and a record of inadequate First Amendment protections for racial and religious minorities. The United States has a long history of not just allowing disparate treatment but specifically excluding racialized religious groups from the access to the United States.

But why is it important to cure our historical amnesia? Why must we name this as an American phenomenon? Who are we to argue when history can be used as a tool for condemning religious exclusion, past and present? Because historical inaccuracies cut both ways and cause a dangerous complacency.

A shallow historical understanding allows the mayor of Roanoke to point to Roosevelt’s internment of Japanese Americans as evidence about the need to oppose Syrian refugees. It can let a New Hampshire politician follow suit in citing internment as support for Trump’s proposal to ban Muslims. A deeper historical knowledge allows one to see the failures of internment to provide security, the horrible impact on people, and the more recent general consensus that this was a national disgrace—not a model for further action. Historical headlines in lieu of more complete understandings can be a problem as we try to define an acceptable American response to new dangers.

Former Supreme Court Justice Tom Clark represented the U.S. Justice Department during Japanese internment. When looking back on the Korematsu case, the 1944 Supreme Court decision that permitted the continued internment of people of Japanese descent, he notes:

The truth is—as this deplorable experience proves—that constitutions and laws are not sufficient of themselves … Despite the unequivocal language of the Constitution of the United States that the writ of habeas corpus shall not be suspended, and despite the Fifth Amendment’s command that no person shall be deprived of life, liberty or property without due process of law, both of these constitutional safeguards were denied.

We cannot rely solely on our constitution. We cannot rely simply on assertions about “American values” to defend us against policies that threaten religious freedom, tolerance, equality and democracy. A fuller understanding of history illuminates that differential treatment and exclusion of a constructed “dangerous” racial religious other is foundational to the American political system, not outside of it. History shows that, even in the United States of America, we need to be vigilant and willing to stand up quickly against persecution.

Robin Dale Jacobson is associate professor of politics and government at the University of Puget Sound. She is the author of The New Nativism and co-editor of the volume Faith and Race in American Political Life.