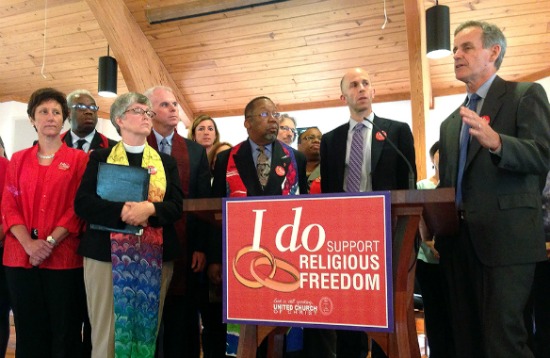

(Matt Comer/QNotes)

On April 28, 2014, the United Church of Christ—joined by clergy from Lutheran, Baptist, Unitarian Universalist, and Jewish congregations—and six same-sex couples filed a lawsuit in the federal district court in Charlotte, North Carolina, challenging the constitutionality of the state’s ban on same-sex marriage. Similar to the 66 pending lawsuits in other jurisdictions across the country (including two lawsuits in the federal district court in Greensboro, North Carolina), these plaintiffs allege that North Carolina’s “Amendment One,” approved in 2012 by 61 percent of the state’s voters, violates the Due Process and Equal Protection Clauses of the U.S. Constitution. What makes this lawsuit unique, according to plaintiffs’ lawyers, in addition to the participation of a religious denomination as a plaintiff in a lawsuit challenging a same-sex marriage ban, is the claim that Amendment One violates the Free Exercise Clause of the U.S. Constitution.

In other words, along with the now familiar argument about equality under the law, plaintiffs in General Synod of the United Church of Christ v. Cooper contend that North Carolina’s ban on same-sex marriage violates their religious liberty. The specific articulation of this argument in court documents and statements to the press raises a number of new questions about the marriage equality movement and sharpens some existing ones.

At the press conference announcing the filing of the lawsuit, the Rev. Nancy Ellett Allison, pastor of Holy Covenant United Church of Christ (UCC) in Charlotte, said, “North Carolina’s laws prohibiting same-gender marriage designate some citizens as unfit for the blessings of God. We reject that notion. As all God’s children are welcome to receive the sacraments of communion and of baptism, so all of God’s children should be able to receive the sacrament of holy union and marriage.” While Allison’s proclamation has incontrovertible rhetorical power, the soundness of her legal and theological analysis is less certain.

As in almost every jurisdiction, clergy in North Carolina are, in effect, deputized to represent the state at marriage ceremonies, to receive marriage licenses issued by the state, and to return those licenses to the register of deeds so that they can be duly recorded. North Carolina law also states that any person “authorized to solemnize a marriage under the laws of this state who marries any couple without a license being first delivered to that person … shall … pay two hundred dollars to any person who sues therefore, and shall also be guilty of a Class 1 misdemeanor” (§ 51-7). Such a misdemeanor carries a penalty of up to 45 days in jail for the first four offenses and up to 120 days in jail for five or more offenses (§ 15A-1340.23). Plaintiffs in General Synod contend that this second provision criminalizes officiating at same-sex weddings, because the couples being married can never obtain the requisite license, thereby infringing on the religious liberty of the ministers to conduct such weddings and on the religious liberty of the couples to receive the blessings of their faith communities.

Contrary to plaintiffs’ assertions, clergy in North Carolina are absolutely free to confer any number of blessings on same-sex couples. They may even be able to grant such couples access to the sacrament of marriage. What they may be unable to do is officiate over the statutory “ceremony of marriage.” The central question: Is this a legal transaction or a religious ritual? Given that federal courts typically interpret statutes in a manner that will avoid constitutional issues, it seems likely that a court would restrict the statute’s meaning to the former. Moreover, given that North Carolina’s prohibition on same-sex marriage explicitly leaves open the possibility of legal recognition of contracts between private parties and its marriage codes allow clergy to officiate over a “confirmation ceremony” that is distinct from a “ceremony of marriage,” the court would have statutory grounds to avoid the implication General Synod draws from the state’s marriage code.

But the fact that the statute could be read to reach the sacramental life of the church highlights the complicated status of clergy when they officiate at weddings. When a minister pronounces an opposite-sex couple married, it is a declaration with both legal and religious implications: the state and the spirit act through the clergy member to confer a new status on the couple. From a theological perspective, which most likely informs Allison’s rejection of the notion that some citizens are unfit to receive the blessings of God through the sacraments of the church, the state cannot meaningfully curtail a clergy member’s capacity to act religiously, even if it punishes such conduct. Since at least 2005, the UCC has endorsed the right of same-sex couples to receive the blessing of the church on their relationships; insofar as the state prevents Allison and her co-plaintiffs from conferring that specific blessing, then it is, indeed, impinging on their free exercise of the full range of their religious duties and that must surely be a violation of the First Amendment. Insofar as the state is setting out the conditions by which clergy, as bureaucratic minions, can effect legally binding marriages that it is then compelled to recognize, then there is no First Amendment issue. If the plaintiffs are seeking the power to perform legally binding marriages, as an exercise of religious liberty, then they are asking the state to endorse their specific theological vision of marriage and, contrary to their claims, are indeed seeking to impose their views on a broader public.

The difficulty, of course, is that a minister authorized to solemnize a marriage under the laws of North Carolina is acting as government functionary and religious dignitary simultaneously. If clergy want to protect religious liberty, why are they willing to serve as state delegates in wedding ceremonies under any circumstances? Why are these churches and synagogues so willing to serve as branch offices of the register of deeds? Why are these ministers and rabbis willing to be paper-pushers for the state? Why not surrender “marriage” to the state’s offices and employees, thereby making it clear that clergy offer a unique, fully distinct, form of blessing and recognition to the couple pledging commitment to one another? This would not only be cleaner, but also sounder—from both a legal and a theological perspective. The ability of the state to infringe on the free exercise of religion in this context, the need for plaintiffs to demand a separation of church and state at this moment, depends on a prior entanglement of the church with the state in regard to marriage, an entanglement in which both fully and willingly participated.

In addition to its revelation of the complex imbrication of church and state in relation to marriage, this lawsuit reveals a failure of political imagination within the marriage equality movement as a whole. While the clergy plaintiffs in this case have undoubtedly flouted North Carolina law through their conduct, and express their desire to act contrary to the state’s unwillingness to recognize same-sex marriages, their press statements and legal allegations cede astonishing power to the state to confer dignity, recognition, and worth. Quite unlike communities of caregivers during the worst of the AIDS years who claimed the status of family and kinship despite government diffidence and religious hostility, too many voices in the marriage equality movement equate legal sanction of relationships with the worth of those relationships. One of the most telling examples of this tendency came from Kris Perry, one of the lesbian plaintiffs in the California Proposition 8 case. After the Supreme Court announced its decision in that case, Perry stated from the steps of the Supreme Court, “Today, we can go back to California and say to our own children, all four of our boys, your family is just as good as everybody else’s family, we love you as much as anybody else’s parents love their kids.” Today, we can do this? Because the Supreme Court said it was okay? Surely Perry was not waiting for a decision from the Court to tell her boys that their family was as good as everyone else’s, to assure them of her love? While it may seem unfair—curmudgeonly even—to focus this insistently on rhetorical choices, it seems vital to think carefully about the long-term consequences of a political movement that is fundamentally—fetishistically even—invested in state recognition over resistance and refusal of the marked limitation of the state’s and the wider culture’s limited imagination concerning kinship formations and erotic intimacies. What does it mean that religious leaders are turning to the state, rather than their own institutions, as the source and site of recognition? What would it mean to rely on, to ground one’s faith in, to claim fully and completely, the power and promise of the rites and rituals of religious communities over and above the pronouncements of the state?

This lawsuit also reveals a fundamental fixation on marriage itself. The complaint’s opening paragraph quotes, with approval, the Supreme Court’s assessment that “marriage is ‘the most important relation in life.’” When discussing the lawsuit, Luke Largess, a partner at the law firm representing the plaintiffs, observed, “There is no event in the life of a church that is more holy and happy than a wedding.”

It is surely worthy of note—as a historical, cultural, political and theological matter—that a Christian denomination and several Christian pastors were willing to be party to a lawsuit that claimed the marital relation was the most important relation in life. The marital relation. Not the relation to God, or to Jesus, or to the faith community itself, but the relation to one’s spouse. Similarly, Largess’ comment, even if it is an empirically accurate description about what most excites and enlivens a community, is also remarkable. It is not baptism, or conversion, or testimony, or confirmation, or the Eucharist that Largess identifies as the most holy event in the life of a church: it is a wedding. Given that marriage operated under a certain suspicion for quite a long time in the history of Christian communities, and given that the foundational texts of the tradition have very negative things to say about marriage, especially insofar as it competes with loyalty to the broader community, these statements reveal something about the contemporary moment, and the reorientation of Christian communities. This reorientation is further attested when the complaint later states that access to marriage should be extended to same-sex couples because this will “serve as a building block for larger family units”—since building larger families is so obviously a duty of the right-minded Christian. (I specify my claims here because marriage has a specific history within Christian communities. For plaintiff Rabbi Jonathan Freirich similar, but not identical, questions could be posed, given the specific history of marriage within Judaism.)

More importantly, however, it is unclear how these statements can be reconciled with broader sentiments about the dignity of all God’s children. On the website devoted to coverage of the lawsuit, another plaintiff, the Rev. Nancy Kraft, pastor of Holy Lutheran Church, declares, “We celebrate sexual orientation as a gift and encourage all people, whether gay or straight, to live authentically and fully as the people God created them to be.” As the above quotations suggest, however, one will always live a bit more authentically, and a bit more fully, if one lives as married. In describing the harms of denying access to marriage to same-sex couples, the complaint contends that marriage “creates more stable futures for the couples.” This language not only distinguishes, it evaluates. And a hierarchical valuation of relationships that admits, rather than excludes, lesbian and gay couples remains, nevertheless, a hierarchical valuation. Celebrating the sanctity of marriage solidifies the dignity of marriage, it’s an open question whether that cultural capital trickles down to lesbians and gay men who are unable or unwilling to participate in the institution.

The most significant consequence of this lawsuit—ironic, tragic or terrifying, depending on one’s mood—is that it strengthens claims by those who would cite religious liberty as a reason to avoid the consequence of general laws. As reported by Jaweed Kaleem and Lila Shapiro for the Huffington Post, Columbia law professor Katherine Franke characterized the strategy of conservative opponents of same-sex marriage, and their appeals to religious liberty, in the following manner: “You can have your laws, they just don’t apply to me.” This is precisely what plaintiffs in General Synod argue: The state of North Carolina has a set of values regarding marriage; these values are inconsistent with our religious convictions; therefore, we should be exempt from laws which would sanction us for following our religious convictions. There is no way to distinguish this argument, in principle, from the argument of the person who, based on religious convictions, wants to be exempt from anti-discrimination laws. While the religious freedom claims of a rabbi to perform religious duties may have more initial plausibility than the religious freedom claims of a bakery-shop owner to perform commercial duties, courts cannot draw such distinctions without distinguishing between authentic and inauthentic religion, and genuine and false religious obligations. Surely nothing is a greater infringement of the free exercise of religion than that kind of judicial sorting.

There are many reasons to be heartened by the UCC’s lawsuit. If nothing else, it is a reminder of the long history of religiously motivated advocacy for, rather than religiously motivation vilification of, lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender persons. But the lawsuit also reveals the messy entanglement of the state and religion around marriage and sexuality—a complex nest of thorny questions that will likely only get more fractious and fraught in years to come.

Kent L. Brintnall is the Bonnie E. Cone Early-Career Professor in Teaching at The University of North Carolina at Charlotte, where he is affiliated with the Religious Studies Department and the Women’s & Gender Studies Program. Prior to becoming a professor, he worked for several years as a staff attorney for the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals in San Francisco.