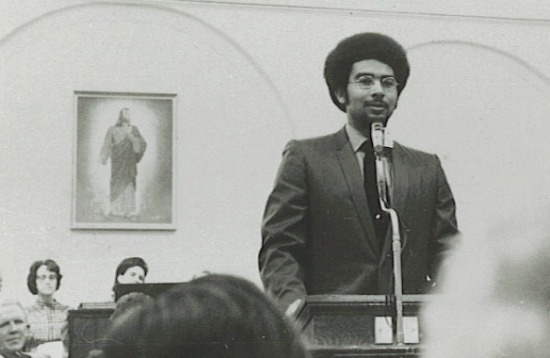

(Courtesy of Darius Gray) Darius Gray, the first president of Genesis Group, a black Mormon support organization, speaks at the group’s first meeting in 1971.

Last Friday, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS) made history by confronting its own history. For the first time, the LDS Church recognized and repudiated its racist past. And it did so, fittingly enough, in the form of a detailed history lesson.

For more than a century, Mormons barred black members from full participation in the church, most notably in the form of the “priesthood ban,” which kept black men from ordination in the all but universal (for men) Mormon priesthood. That practice ended in 1978 when the church’s prophets received a revelation instructing them to do so. Yet, for some 35 years, the church hierarchy never directly addressed the ban’s origins and the beliefs used to justify it for more than 130 years—until now.

On December 6, at 5 p.m. Mountain Time, the LDS Church added a new lesson on race and church history to its “Gospel Topics” website, the church’s official resource for historical and theological issues. For scholars of Mormonism, there is little new in the 2,000-word history lesson (not including some two-dozen supporting footnotes) that an anonymous group of officially sanctioned church historians composed. Since the 1970s Mormon and non-Mormon historians alike working outside the hierarchy have published scores of journal articles and books detailing the origins of the priesthood ban and other church practices.

But for Mormons (or Mormon observers like me), it is the new lesson of how the LDS Church has historically dealt with issues of race, and how it deals with them today, that is most significant. The new statement recognizes that its own leaders—leaders whom Mormons consider prophets of God capable of receiving new revelations and authorized to speak on behalf of the church—used racist views about black people’s supposed spiritual inferiority to justify excluding black men from the priesthood and preventing black couples from marrying in Mormon temples. In Mormon soteriology, this meant that blacks were also barred from the highest levels of heaven.

Now church officials acknowledge that their predecessors were wrong. The following is the most direct and the most explicit passage:

Today, the Church disavows the theories advanced in the past that black skin is a sign of divine disfavor or curse, or that it reflects actions in premortal life; that mixed-race marriages are a sin; or that blacks are or people of any other race or ethnicity are inferior in any way to anyone else. Church leaders today unequivocally condemn all racism, past and present, in any form.

Reading between the lines, this new statement on race reflects what the LDS Church has learned from heightened scrutiny in recent years—during the so-called “Mormon Moment”—when a presidential campaign and a Broadway musical had America and the world investigating the faith. While avoiding an outright apology about its past, the LDS leadership in Salt Lake is attempting to address issues within Mormon culture, as well as perceptions of the faith in American political culture, and beyond.

In 2012, Randy Bott, a celebrated professor at the church-owned Brigham Young University, rehearsed for a Washington Post reporter some of the most offensive justifications for Mormon racial exclusion—and did so in the midst of Mitt Romney’s 2012 run for the White House. Before that controversy, the LDS Church long insisted that its 1978 declaration ending the priesthood ban spoke for itself and that nothing more needed to be said. In response to the Bott controversy, the church issued an official statement condemning racism. And just this past March, the church added an introductory note to the canonized version of the 1978 declaration, in which the church recognized the existence of a handful of black Mormons in the early years of the church. And yet, because the racist beliefs taken from the writings of past prophets have continued to circulate during Sunday school lessons, at Mormon missionary training centers, and even at the church’s flagship university, Mormons, black and white alike, have pressed the church leaders to say and do more.

With its new statement, the church finally said more. To be sure, the content of the statement has and should continue to be scrutinized. In it, the church asserts that the views on race promulgated by certain Mormon prophets, most notably Brigham Young and longtime Church Historian (and briefly Church President) Joseph Fielding Smith, were merely the “opinions of men,” and not the official views of church prophets—despite evidence that these prophets believed they were speaking or writing as official church spokesmen. Also, the statement offered no apology, as some have called for. And while black Mormon leaders like Don Harwell, president of Genesis Group, the black Mormon support organization, welcomed the statement as “better late than never,” he also called it “way past due.” This is especially true for black and mixed-race children who have left the church because they could no longer (or chose not to) endure the “racist folklore” about black spiritual inferiority, which up until last Friday went unchallenged by church hierarchy.

By rejecting the racist beliefs held by past prophets, the LDS Church hopes that discussions of race will shift from divine curses to the divine mandate to proclaim “that the redemption through Jesus Christ is available to the entire human family.” The church hopes that, on Sunday mornings in Utah and in mission fields in Ghana, Mormons now have the resources to contextualize their racially-exclusive past while celebrating their racially-diverse present and future.

There is another, more implicit lesson contained in this new statement; that is about how the LDS Church is coming to terms with the realities of church history in a digital age. For example, if the publication of this new history lesson was such an important event, why didn’t the church’s robust Public Affairs office send out a press release announcing it? In fact, why was it released as part of the “Friday news dump,” suggesting that the church wanted to avoid media scrutiny? The answer is that the LDS Church, which has been wary of social media, has learned to use it for its own purposes. The LDS hierarchy has come to recognize that the Internet is awash in a sea of unflattering accounts of the church’s history—especially about race and polygamy—accounts that more and more young people have turned to for answers, leading some to doubt, even defection. Yet the Internet is also home to hundreds of blogs, which are run by thousands of faithful Mormons, dedicated to studying Mormon Church history. When it came to this new gospel lesson, the church believed that it did not need to publicize the new lesson itself. Instead, it betted that the so-called “Bloggernacle” would do that work on the church’s behalf.

Those who click on one of the thousands of posted links to this new “Gospel Topic” may come to agree that today’s LDS Church is in continuity with the earliest period of its history, when its original mandate of racial universalism was carried out. In this view, the time between 1847 and the origins of the ban and the 1978 revelation end was the aberration. And this church, which increasingly recognizes its own fallibilities, or at least the fallibilities of its leaders, is working to set the history straight. Still others will find this new history lesson, however groundbreaking, wanting—in particular wanting of an apology. As my colleague and Mormon scholar Gina Colvin has written, the “generations and generations” of black people who were told that they were inferior “in God’s eyes,” the Mormons, black and white, of good faith who spoke out against the church’s racism, and even “the white folk who have been led astray by a vicious doctrine [of black spiritual inferiority] up held by white men … They deserve an apology.”

At the bottom of the new statement, the LDS Church acknowledges the critical role historians have played toward the goal of rectifying the record on the church’s relationship with people of African descent. These historians have been able to do this because of the recognition that the church need not be tied to its own past. Resources exist—the philosopher Paul Ricoeur called them “traces” of history forgotten but not gone—to help revise the long-accepted official narrative about race and the LDS Church. And for the historians who wrote this new statement, those resources exist in the archives of the LDS Church History Library.

Here’s hoping that, when it comes to race, the LDS Church—along with all American institutions—continue to make and remake history.

Max Perry Mueller is a contributing editor to Religion & Politics.