In 2011, the Colorado-based Personhood USA ministry made Mississippi the latest staging ground in its campaign to amend a state constitution to define “personhood” to “include every human being from the moment of fertilization.” Personhood USA chose Mississippi for a specific reason. America’s most religious state (at least according a recent Pew poll) is home to the ultra-conservative American Family Association and the anti-abortion Baptist State Convention. Personhood USA believed that Mississippi’s conservative Christians would mobilize to help pass the measure, known locally as Ballot Initiative 26, by wide margins.

And mobilize they did. A coalition of imported and homegrown activists flooded Mississippi’s airwaves with pro-personhood ads and blanketed the state with yard signs urging Mississippians to “Vote Yes on 26!” Journalists from around the country flocked to the Magnolia State, which once again made national headlines for its hard-line social conservatism. Despite polls showing an electorate split evenly between supporters and opponents of the measure, America’s newspapers of record, including The New York Times and The Washington Post deemed the outcome foreordained.

But the polls and the pundits were wrong. The amendment failed spectacularly, by a margin of 58 to 42 percent. Seemingly as quickly as they arrived, the national media decamped from Mississippi. Mississippi’s imminent passage of the Personhood amendment was big news. The initiative’s defeat was not.

Why didn’t pundits, politicians, and activists stop to ask how they had been so wrong about the voters in Mississippi? The answer is that when Mississippi doesn’t hew to simple narratives, Americans no longer know how to talk about it. In the national imagination, Mississippi is the state of extremes: the poorest state, the fattest state, and the most conservative state. But especially when it comes to Mississippi’s place as America’s most religious state, there is rarely room, it seems, for a more complex narrative. The Personhood amendment’s unexpected failure demonstrates that there are complicated social and political realities in Mississippi, realities that are not captured in political prediction models that assume that exceptionally high rates of church attendance and professions of faith redound to knee-jerk social conservatism in the voting booth.

The tendency to reduce Mississippito a set of statistics, most of them regrettable, is not new. In September 1931, H. L. Mencken completed a comparative analysis of the United States in which he concluded that by nearly every possible measure—education, wealth, culture, health, and political participation—Mississippi stood “without a serious rival to the lamentable preeminence of the Worst American State.” Certainly, Mencken, the sharp-penned journalist whose disdain for the South was legendary, did not always represent broader American opinion. Yet Mencken was right that his conclusions about Mississippi would “probably surprise no one,” at least no one outside of Mississippi. Like many journalists of his day, Mencken linked Mississippi’s poverty with its reactionary politics and tied them both to the state’s high concentration of white evangelical Christians.

Since Mencken’s time, not much has changed. American social critics still think religion determines Mississippians’ politics. Yet Mississippi voters are sometimes unpredictable. In the voting booth, Mississippians have repeatedly ignored the dictates of the state’s religious leaders. For instance, in 1932, Protestant ministers statewide denounced presidential candidate Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s campaign promise to end Prohibition. Few trusted Herbert Hoover either. The state’s Methodist paper called the Republican president “amphibious” when he refused to take a firm stand as a “wet” or a “dry.” Nonetheless, many of the state’s Protestant clergy deemed the incumbent a safer option than Roosevelt, and they called for Mississippians to protect Prohibition at the polls.

Yet the state’s electorate ignored appeals from the pulpit and the religious press. Mississippi voters echoed the more practical sentiments of one incensed churchwoman. Everyone, she said, knew that Prohibition was a well-intentioned failure—everyone except “the preachers [who] are sticking their heads in the ground like the ostrich.” Despite many ministers’ hard work to promote Hoover, 96 percent of the Mississippi electorate followed this Christian woman’s example and voted Roosevelt into office. In solidly Democratic Mississippi, such a vote hardly represented a referendum on religion, or even Prohibition. Indeed, Mississippi remained a “dry” state until 1966. But the 1932 election demonstrated that Mississippians made political decisions based on a range of factors. They did not merely vote as their ministers instructed.

For many Mississippians, at the voting booth race has mattered more than religion. The state pioneered black disfranchisement with its 1890 Constitution, which instituted a poll tax and literacy test that also disenfranchised some poor white voters. Because the state’s population was half African American and predominantly poor, Jim Crow meant Mississippi voters in 1932 were almost all white, and disproportionately middle and upper class. This despite the fact that many outside observers have long caricatured the typical Mississippian as poor, white, illiterate, fanatically religious, and racist. Mencken set this tone when he concluded in his 1931 study, that the state’s “[white] native stock of excellent blood” had no choice but to flee elsewhere, leaving behind “hordes of barbaric peasants.”

The first time that black Mississippians entered many Americans’ consciousness was when they appeared on national television in the 1960s, fighting to end segregation and secure the right to vote. Evening news broadcasts streamed images of young African Americans sitting at lunch counters in Jackson in 1963, and lined up outside their local voter registration offices during 1964’s famous Freedom Summer.

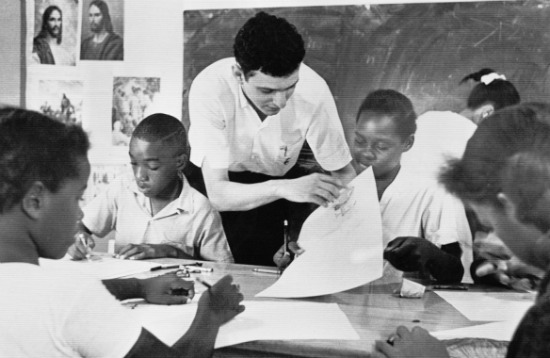

To many Americans observing Mississippi through their TV sets, black churches seemed to be the soul of the civil rights movement. But the monolithic “black church” was more myth than reality. To be sure, many black churches supported civil rights. Freedom Schools met in black churches all over Mississippi, including Mt. Zion Baptist Church in Hattiesburg, which also hosted organizational meetings for the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party. A rash of church bombings and burnings in the 1960s demonstrated that white supremacists recognized that black churches could serve as potent organizations for social change. Freedom Summer’s most famous martyrs, James Chaney, Michael Schwerner, and Andrew Goodman, were investigating the burning of a church that had opened a Freedom School when they were murdered near Philadelphia, Mississippi, by local Klansman, including the county’s deputy sheriff, Cecil Price. Still, many black churches remained on the sidelines. The threat of white reprisal, and the fear that civil rights activism would upset friendly relationships with some members of the white power structure, silenced many black congregations.

The characterization of the “white church” as the unrepentant bastion of bigotry and hypocrisy was also inaccurate. During the civil rights era, the white religious majority that remained opposed to racial change faced mounting criticism from a growing minority of white moderates within and outside the state. A few white liberal Christians helped rebuild bombed churches. Some also began to speak out in favor of civil rights for black Mississippians. In 1963, twenty-eight white Methodist clergy signed a public statement entitled “Born of Conviction,” which affirmed the church’s stand against “discrimination because of race, color, or creed.” Still, for taking such a stance, many of these ministers had their tires slashed and the KKK burned crosses on their front lawns. In less than a year, 20 out of the 28 signatories had left the state.

After 1964, Mississippi slipped from the headlines, leaving many to assume that Freedom Summer’s goals of black enfranchisement and equality were realized. Yet even now, African Americans continue to push for full access to the state’s political and economic levers. In 2011, on the same Election Day that Mississippians rejected the Personhood initiative, Mississippians also approved a voter identification amendment, which many believe will limit African Americans’ access to the polls. In response, some black churches have again become sites for mobilizing and educating a marginalized electorate.

Observers will no doubt continue to decry Mississippi as the nation’s most reactionary backwater, or, alternately, celebrate it as the bedrock of American Christian conservatism. But the South’s poorest and most religious state still feels the pull of forces—demographic change, industrial development, and suburbanization—that complicate outdated Bible Belt stereotypes. Public declarations and private grumbling from the state’s business and professional class, including statements of opposition from the medical community, undercut any semblance of a united front on the Personhood amendment. Even former Republican Governor Haley Barbour expressed reservations about the unintended consequences of Initiative 26.

But the initiative did not simply fall victim to business sense. Mississippi’s Episcopal and Methodist bishops also spoke out in opposition to the amendment, and the Catholic bishop refused to endorse it. The minister of Jackson’s oldest black church and rabbis of two prominent synagogues joined them. Two anti-initiative coalitions, Mississippians for Healthy Families and Parents Against MS 26, included people of faith—many of them deeply conservative—who shared the clergy’s concerns about the amendment’s far-reaching implications for women’s health and fertility. For instance, these organizations argued that an amendment designating life as beginning at the “moment of fertilization” could prevent doctors from performing life-saving procedures on pregnant women, threaten the legality of in-vitro fertilization, and even outlaw the birth control pill.

The failure of Initiative 26 was no anomaly. Thoughtful Mississippians have long organized into interfaith alliances, launched grassroots informational campaigns, and together put their shoulders to the wheel to do the hard work of racial reconciliation and policy reform. Mississippi may be the nation’s most religious state, and it is certainly one of its reddest. But it is also a place far more complex, dynamic, and—occasionally—surprising than most outside commentators care to admit.

Alison Collis Greene is an assistant professor of history at Mississippi State University.