(Red Kerce/State Archives of Florida)

On Elvy Edison Callaway’s hand-drawn map of northwest Florida, the Jim Woodruff Dam over the Apalachicola River looks like the narrow wrist of a giant hand. Just north of the dam, near the Florida-Georgia border, the Apalachicola splits into four fingers. Callaway has neatly labeled each river with its Floridian and its Biblical name: The Chattahoochee would be the Tigris, Fish Pond Creek the Pishon, Flint River the Gihon, and Spring Creek the Euphrates. Callaway, a white-haired bespectacled lawyer, announced in his 1971 book In the Beginning that this four-headed river system “proves beyond all doubt that the Bible account is true, and that the Garden was in the Apalachicola Valley of West Florida.”

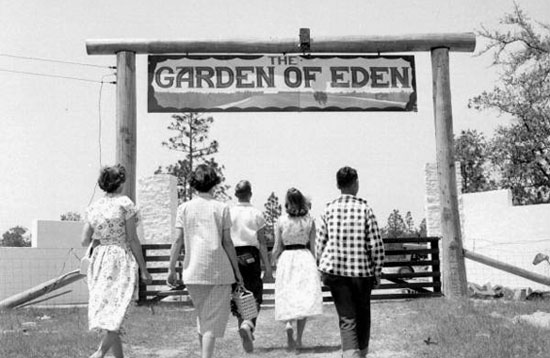

Biblical truth was not the message one would expect to hear from a man named after the father of American invention, Thomas Alva Edison, or from a lawyer who’d taken Clarence Darrow’s side in the legendary Scopes trial. But Callaway was neither a typical progressive nor a typical Bible reader. A former Baptist turned religious freethinker, a staunch Republican in the age of the New Deal, he was a pro-woman, pro-market entrepreneur. He also believed that God created man in the flat piney swamps of the Florida Panhandle. But his Eden was hardly traditional; it was open to everybody. In 1956 he opened his Garden of Eden park, where visitors could pay $1.10 to see paradise for themselves. Callaway spent thirty years trying to convince people to do just that. He knew how to handle the skeptics—he’d been one himself most of his life.

Religion and Reason

Callaway’s distrust of religion extended back to his youth. Born in 1889, and raised on a farm in tiny Weogufka, Alabama, young Callaway fell out with his father’s hard-line Baptist church. Just before Christmas, 1908, when Elvy was eighteen, he befriended a young female schoolteacher, who was new in town and not yet a church member. The two began taking Elvy’s horse-drawn buggy to local (non-Baptist) square dances. Since Baptists were forbidden by their church to actually dance, at first Callaway would simply “take a seat in the corner and look on.” But after several nights as a spectator, he “finally reached the conclusion that any God who would condemn a young man to eternal damnation for what appeared to me an innocent amusement was a monster instead of a loving father.” He did not pretend this was an entirely theological point: “My interest in the young lady helped me to reach this decision.”

One Sunday three weeks later, his minister called on Callaway to apologize for his square-dancing transgressions. When he refused, motions were made to charge him with “revelry” and begin proceedings against him. Callaway responded: “I have no desire to associate with a bunch of ignorant bigots.” He then picked up his hat and walked out.

As Callaway told it in his 1934 book The Other Side of the South, this was the moment he converted to secularism. Without the pressure of the church, he studied and read whatever he could get his hands on, hiding his books in the woods and barns to keep his parents from destroying them. It was only a short step from book-reading to Jacksonville State University in Jacksonville, Alabama. He left for school that very year, 1908, and by 1911 he had married Annie Levie—who may or may not be the good woman from the square dances. By 1917, he was running a law practice in Lowndes, Mississippi, and he and his wife had a son, William.

Soon they moved south to Lakeland, a good-sized town in central Florida, about halfway down the peninsula. There, in the 1920s and 30s, he prosecuted cases for the newly formed NAACP. Callaway claimed a long lineage of forward-thinkers. He wrote that his great-grandfather—who had built the church that he made such a dramatic exit from—had freed his 103 slaves in 1856. Callaway’s views on “the situation of the Negro” were progressive for his time and place, as were his views on the separation of church and state. He also claimed friendship with Clarence Darrow, and endorsed his pro-evolution position in the Scopes Trial. All of these positions would have been minority views in central Florida.

In his opinion, there were two forces needed to save the South, America, and the world: religion and reason. Ever the lawyer, he reserved the right to define these timeworn terms. “What I mean by religion is love, patience, toleration, sympathy, kindness, vicarious service, honesty, truth, a love of and for the beautiful, a hunger for knowledge and wisdom, a belief that right thought, right conduct, right example is a magnet sufficient within itself to attract men and women away from excesses and evils.” Who could argue with that? He did not stop to define “reason,” perhaps because he hadn’t spent so much time battling against it. Reason needed no definition. “If we can ever have both religion and reason,” he continued, “the South will be the ‘Garden of Eden’ of this earth.” Callaway was being figurative here; he meant that the South had potential for perfection. It was politics that took him from a figurative Eden to a literal one.

A Voice in the Wilderness

Ever since his teenage square-dance rebellion, Callaway had had a strong contrarian streak. In 1920, he was a spectator at the Republican convention in Chicago that nominated Warren G. Harding for President. But once again he wasn’t content on the sidelines; in 1928 he served as a delegate, helping nominate Hoover in St. Louis. By 1929 he was chairman of the Florida Republican Party, in a state so Democratic that, as Callaway wrote: “It is known to every informed Southerner that one who opposes, questions or criticizes any President branded, like a cow in the woods, with the designation ‘Democrat,’ commits an unpardonable sin and is looked upon as a traitor to all that is sacred and holy.” Callaway chafed at anybody telling him what was or was not a sacred cow.

The Depression era was an awkward time to be a free-market libertarian Republican, to say the least. Unemployment had gone from 4 percent to 25 percent, and in 1932 Democrat Franklin Delano Roosevelt was overwhelmingly elected for the first of four terms. He spent his first 100 days in office meeting with Congress daily in a marathon law-making session, during which they granted every one of his requests for aid and regulation.

Callaway was suspicious of this kind of Democratic party-machine unanimity; it offended his pride as an individualist and an entrepreneur. He opposed everything Congress and Roosevelt favored—except the reversal of Prohibition, which he was all for. In 1936 Callaway ran for Florida governor on an anti-welfare platform. He proudly denounced Roosevelt’s wildly popular New Deal. He wanted the return of the gold standard. He wanted the new banking regulation reversed. He lost, dramatically, and never quite got over it.

Callaway returned to his law practice in Lakeland, and tried to content himself with armchair politicking. Two years after his defeat, the Washington Post published a letter in which he accused the New Deal Democratic Party—“economic royalists” all—of buying a Florida Senate election. This, wrote Callaway, was not progress, but ignorance. But nobody paid any attention. And then America got itself into another World War—another Roosevelt mistake, as Callaway saw it. All Callaway’s libertarian hopes seemed lost.

A New Calling

Just after the end of World War II, Elvy Callaway Sr. paid a visit to one Dr. Brown Landone in Winter Park, not far from Lakeland. The 98-year-old Landone had once been a medical doctor in New York City. Now, in his Florida retirement, he had taken up metaphysics. With the help of a large secretarial staff, he produced prodigious quantities of inspirational literature. Among the titles: “Transforming Your Life in 24 Hours,” “Spiritual Revelations of the Bible,” and “Prophecies of Melchizidek in the Great Pyramid and the Seven Temples.” Landone’s followers felt he had a special talent for bringing a scientific rigor to mystical problems. Callaway describes his meeting with Landone as a “calling.”

It is unclear whether Callaway’s calling happened before or after he got a divorce. But during the same month he met with Landone, in October of 1945, Elvy split from Annie Levie after more than thirty years of marriage. At such a delicate point in his life, Dr. Landone’s call to Callaway to “close his law offices and his home in Lakeland,” must have seemed particularly expedient.

Landone ordered him to move to a different part of Florida, somewhere farther north, where he would receive the mystical knowledge necessary to perform an unspecified sacred mission, sponsored by the Order of the Melchizidek. According to Landone, Melchizedek gave his name to a mysterious order of priests that operate by means of the “Teleois Key,” a numerological system relying on the numbers 1, 4, and 7 to transmit wisdom throughout the ages. Callaway was so drawn to the system that he left his family behind in Lakeland to follow its teachings. Perhaps Landone’s neat formulations of life and truth appealed to Callaway’s developing sense of reason and his idiosyncratic sense of religion. Perhaps his wife Annie had been the “reason” to his “religion,” and without her he came unmoored. In any case, for the first time in almost forty years, he began to lean again toward religion—albeit a very idiosyncratic faith of his own making.