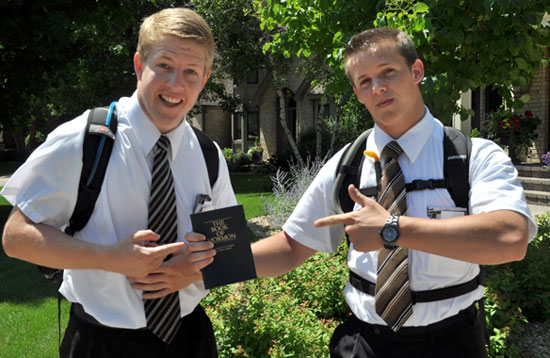

(Leif Hagen)

Unless you have been living in a cave or asleep for the last half year, you know that we are living in an era that the media has dubbed the “Mormon moment.” Aided by the religious affiliation of not one but two Mormons, Mitt Romney and Jon Huntsman, in the latest presidential election cycle, this moment has led to a flurry of media interest in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. It also hasn’t hurt that at about the same time the creators of South Park, Trey Parker and Matt Stone, produced The Book of Mormon, a smash Broadway musical that placed the Latter-day Saints squarely in the public eye. In other words, we’ve seen a “perfect storm” of interest in all things Mormon in the past year.

I must admit to feeling some dismay about this course of events. I have been teaching a class on Mormonism at the University of North Carolina since 1999, and several years back I realized that there was a tremendous need for greater knowledge of this religious tradition. So, I am in the midst of researching and writing a book about the history and current status of Mormonism. And the more that happens in the news, of course, the more there is to write about—so, as a historian I just want to stop the deluge of news for a few days. In my larger project I seek to explain the history and current configuration of Mormonism to outsiders. But I also hope to cast light on what the Mormon experience in the United States tells us about the rest of us, about our notions of which differences are valuable and which are threatening, and about our tolerance of religious variety and the limits of that tolerance.

My task is to bring some needed historical perspective to current collective conversations about Mormonism in public life. Because I believe that this moment, like many such events that seem to come out of the blue, actually has been about 100 years in the making. In short, my argument is this: since the beginning of the 20th century Mormons in the U.S. and other Americans have struggled with a particular but pervasive problem: how to recognize Mormons as U.S. citizens, with all the obligations and privileges that attend that designation. The last few years marks only the latest round in a series of events that have shaped, but never completely resolved, this question.

Citizenship may seem like a simple and obvious idea to us today, and its relationship to religious belief and practice has been sorted out in the courts for decades. In the narrow sense, citizenship denotes a particular form of political representation, as well as the potential for participation, in the federal government. So it is worth bearing in mind that throughout the nineteenth century, the Mormon movement was effectively barred from making any substantive claims on U.S. citizenship. Joseph Smith, Jr., a young farmhand from upstate New York, founded the church in 1830. Very soon, however, Mormons were forced to flee the East and regroup in the Midwest—first in Missouri, where in the mid-1830s Mormons began to gather in Jackson and then Clay counties, and later in the newer settlements of Caldwell and Daviess counties. From the start their arrival, coming as it did in large numbers (in the thousands) and through continuing streams of immigrants from both the eastern states and Europe, caused political and economic tensions with older settlers. Following years of sporadic violence and threats on both sides, the Mormons were forced to flee Missouri after Governor Lilburn Boggs issued an order in 1838 declaring that church members should leave the state or be exterminated. A worse fate met them in Nauvoo, Illinois, where after a few years of relative calm Smith was killed by a mob and the community once again forced out. My point in recalling this early history is simply to underscore that, as much as the Mormons appeared to threaten the political stability of older settlements in Missouri and Illinois, their tenure in these states was never long enough or peaceful enough that the issue of Mormons as political actors came to the fore.

The scattering of Mormons after 1844 brought a new chapter to this saga. The religious movement split into a variety of factions, most of which were relatively small and fairly quickly assimilated into American society. The largest group of exiles, perhaps 5,000 or so, moved further west to Utah, where over the next half century they built a self-sufficient society in the Salt Lake Basin. This group, by now known as the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, represented the germ of a community that would grow to over 200,000 people, the majority of them Mormon, by 1890. The U.S. government was not far behind; Mormon settlement in Salt Lake began before the Mexican War, before Utah had any status in American political life and was still a gleam in the eyes of those believers in Manifest Destiny. Once annexation occurred, however, the Mormons found themselves again tangling with the federal government over their practice of polygamy; but this time they were blocked from full participation in the nation because they lived in a territory instead of a state, a district without representation in Washington or the ability to elect its own leadership. Over the next half century the U.S. government and church leaders conducted an elaborate cat and mouse game: the U.S. held out the carrot of Mormon citizenship in exchange for the Mormon promise to obey the laws of the land and discontinue the practice of polygamy. Failing to convince the Church to capitulate, the federal courts turned the screws and made life increasingly difficult for Mormons; by 1890, all church properties, including the LDS sacred temples, were in imminent danger of federal confiscation, and as a result the religious community teetered on the precipice of economic collapse. Finally, in a dramatic meeting of the minds, the Church ended its practice of plural marriage and the U.S. government conferred statehood in 1896.

This, then, is where our story really begins: With statehood came the new problem of the Mormon citizen. Although many Americans had harbored suspicion toward the church for years, the threat that it posed had been contained in the far West and limited in its ability to affect the fortunes of the nation. The nineteenth-century Mormon threat was a moral and symbolic threat, but never seriously a political one. Now, Mormons would be participating in the daily practices of public life. Once statehood was conferred, their “threat” would be unleashed in the halls of Congress and eventually, as we know, would lurk in waiting outside the West Wing itself. The “western” problem of Mormonism now became the internal challenge of the Mormon within the body politic.

If this is how Mormonism looked from the outside, let’s now turn our attention within the religious community. How did the Saints set out to embrace this new political identity? How did individual church members, previously cushioned from the need to become political actors by the disempowering embrace of territorial status, step into this brave new world of citizenship?

THE FIRST THING TO BE said is that the Mormon Church had been honing its public relations skills from its earliest years. There were two simple reasons for this: first, Mormons faced immediate criticism and public defamation from detractors. In 1834, a scant four years after the founding of the new movement, the newspaper editor Eber D. Howe published the scathing Mormonism Unvailed [sic], a compilation of accusations, affidavits, and other evidence of what Howe took to be the frauds perpetrated by Joseph Smith. More criticisms followed, and Mormon apologists early on fell into the pattern of spreading the word through debate and polemic, arts that required superior communication skills. Having been born in the early years of publishing, the Mormon movement availed itself of the latest technology—the printing press—that could help to plead its case to the public. The second reason for their P.R. savvy, connected to the first, was the deeply ingrained Mormon missionary impulse. Smith counseled his followers that their primary task was to spread word of the restoration of the gospel to all peoples; within months of establishing a church, the new prophet sent followers to preach to American Indian populations to the West, and shortly thereafter sent another small band to England to begin a mission to Europeans. Missions required robust marketing skills, and Mormons knew that theirs had to be especially good in places where other Christian groups not only had already landed, but had also spread word about Mormon heresies. Pragmatic in their approach, Mormons sharpened their tools in situations of intense competition for followers and a desire to level the playing field with other Christian groups.

In their years of isolation in Utah, moreover, the Saints also practiced public relations by appealing to the small bands of cross-continental travelers who stopped for a visit among the odd but generous Mormons. Tourism increased dramatically in the 1870s and 1880s with the completion of the railroad, and Mormons used their notoriety as the ideal opportunity to charm guests with their well-appointed hotels, clean city paths, and ingenious agricultural techniques. Dozens of books and memoirs remain as a testimony to this period when “visiting the Mormons” represented the height of adventure travel for many well-heeled Americans—some of whom then became outsider advocates who could testify to Mormon virtues. This was certainly the role played by Elizabeth Kane, a non-believer touring through the Salt Lake Basin in the early 1870s. She had expected to find neglect and despair with the Mormon households she visited, and she actively sought out evidence that polygamy was enslaving women. Instead, she found similarity to her own life: At one stop she met a woman with a tidy house (including a prominently displayed Bible), and had to admit grudgingly that the woman “appeared to be . . . happy and contented.” In her first Mormon Church meeting, Kane searched for the “hopeless, dissatisfied, worn expressions” on the women’s faces that others had led her to expect; instead, she noted that Mormons looked much like any other rural congregation she had encountered.

By the time statehood arrived in Utah, Mormons were ready for America, and they had the skills to meet the challenge of—if not a 24-hour news cycle, then certainly the pace of the various dailies that graced newsstands in 1900. And most Saints met the challenge of Mormon citizenship gladly, knowing that it provided both a measure of security for their own families and community as well as an opportunity to spread their religious message to places that previously had been blocked, if not entirely closed to them. It was in that moment of arrival on the American political scene that the peculiar talents of an oppressed religious community became useful in another sense: the Saints had learned to live with the gaze of the world upon them, and that self-consciousness would become an ally in their campaign to assimilate, to function simultaneously as Mormons and as American citizens.

THE MOST OBVIOUS MEANS of joining the nation was, of course, to become involved in politics by running for office. Indeed, it was the trial in 1904-1907 of elected U.S. Senator Reed Smoot, a church member from Utah who met with fierce resistance to being seated, that precipitated the realization from church leaders that a broader campaign for acceptance would need to be launched. If Mormons were to become citizens, they would need to find a variety of ways to ensure their membership. Smoot eventually was seated, and he served in Congress into the 1930s. But the resistance to his claims, brought not because of anything he had done himself but because of his leadership in a church that was still suspected of breaking federal laws by harboring polygamists, was a lesson learned well by the Saints. Instead, they looked to other modes of inclusion.

Building on the perceived success of the Utah state exhibit at the Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893, Mormon leaders wagered that culture gatherings such as World’s Fairs and Expositions offered a non-threatening way to present a positive image to the American public and to emphasize contributions of the Mormons to the nation. Their first approaches quite purposefully diverted public attention from overtly religious practices. Whereas a focus on religion might have prompted consideration of recent battles over the legacy of polygamy or unusual practices such as baptisms for the dead, early exhibitors instead steered the public gaze toward the economic, agricultural, and technological achievements of Utah (still majority Mormon) and its surrounding areas. In 1904, for example, the Louisiana Purchase Exposition was held in St. Louis, then the fourth largest city in the United States. Utah officials erected a reproduction of Little Zion Valley, showing small farms ringed with mountains, as its agricultural offering. In the Exhibition Palace the Utah displays won prizes in education, mining, metallurgy, and irrigation. A year later the state garnered even more acclaim in Portland, Oregon at the Lewis and Clark Exposition, when the Ogden-based Mormon Tabernacle Choir performed to sold-out crowds. The piece they sang, composed by a fellow church member, was entitled the “Irrigation Ode”—dexterously honoring local technologies and simultaneously showcasing the superior musical skills of the choir. More than 1,000 people were turned away from their final concert, and Mormon leaders considered the show a rousing success in increasing national acceptance of the church.

After a dozen similar forays into public exhibitions, Mormons felt emboldened to present themselves not simply as technological wizards or superior irrigation specialists, but as participants with a religion. By the time of the second World’s Fair in Chicago in 1933, Mormon contributions more overtly addressed the church’s religious distinctiveness. Volunteers distributed religious literature, recited the 100-year history of the church, and proudly displayed a miniature replica of the Salt Lake Tabernacle and Organ to approximately 4,000 visitors per day in the Hall of Religions. Church members clearly saw this achievement as the ideal union of evangelism and positive public relations: One LDS visitor exclaimed about the possibilities: “Twenty-three hundred forty pulsating hours of human contact! One hundred and forty thousand precious minutes of continuous revealment! Hundreds of thousands of tracts and pamphlets distributed to truth seekers!” George S. Romney, great-uncle to Mitt and mission president for the Chicago region, noted how ably the exhibits showcased Mormon family life (now safely monogamous and nuclear in structure), and remarked on how “hungry” visitors seemed to be for the Mormon message.

A SECOND CHARACTERISTIC mode of assimilation employed by Mormon leaders was outreach through educational spokespersons, church members who had been trained outside of the Salt Lake Basin and could serve as bridge builders through both personal connections and common academic interests. Mormons had always valued education, so this seemed like a natural place to forge substantive ties that could help with other enterprises. The most prominent example of this trend can be seen in the career of James Talmage. A British-born convert to the faith, Talmage migrated to Provo, Utah with his family in 1877. After high school Talmage left for the east coast, where he studied chemistry and geology at Lehigh and Johns Hopkins Universities before receiving a PhD from Illinois Wesleyan in 1896. Returning west, Talmage joined the faculty at the University of Utah, where he taught geology. In 1911 he was called as a member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles (the highest level of leadership underneath the Presidency), and served there until 1933.

Along with his skills in science, Talmage was a master of public relations. In 1911 the LDS Church had discovered that the interior of the Salt Lake Temple, considered a sacred site, had secretly been photographed; the perpetrators demanded a $100,000 ransom for the photos. Church leaders agonized over their options until Talmage proposed that the Saints commission their own photos and publish them, a brilliant suggestion that once again gave the Mormons the upper hand in controlling their public image. That same year, the First Presidency—the governing body of the LDS Church—appointed Talmage as an Apostle, and thereafter he served as an exceptionally effective spokesperson. A staunch conservative on matters of scripture, he nonetheless held his own on the speaking circuit of interreligious conferences and exhibitions. In 1915 Talmage orchestrated an invitation to speak as the Church’s representative at the Congress of Religious Philosophies, held in San Francisco as part of the Panama Pacific International Exposition. There, activists such as Emma Goldman held forth on atheism and Murshida Rabia Martin presented on Sufism. Talmage spoke in a session alongside Roman Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, and Protestant luminaries; his paper on “The Philosophical Basis of Mormonism” was later prepared for missionary distribution. In each of these settings, Talmage presented Mormonism as a viable religious option among others, and in this regard his performance of civic parity with other religious leaders was as significant as the words he spoke.

One evident effect of these forged intellectual connections was a score of friendly outsiders who began to publish sympathetic accounts of the church. The Case Against Mormonism (which was, despite its title, a congenial rendering and close analysis of what the author called the “lies” perpetrated against the Saints) appeared in 1915; the author, who used the pen name Robert C. Webb, advertised the book as the product of a “non-Mormon,” and everything in its pages seemed addressed to an educated audience well versed in the fields of economics, sociology, and theology: “What is needed in the premises is a careful and conscientious examination of the origin and claims of ‘Mormonism,’ in order that intelligent people may oppose it intelligently, if so disposed, or, in any event, estimate at a fair appraisal this system of teaching and practice.” Using anti-Mormon excitement as evidence of the significance of the subject, he criticized Christians who would easily dismiss the claims of the faith. “The candid observer of all this can scarcely fail to conclude that there must be something really interesting in a system, in opposition to which people will thus stultify themselves and lie, as so many anti-Mormon writers have done, and which, in spite of the contemptible character ascribed to it, still seems sufficiently important to excite so great antipathy.” The author was, it turned out, an Episcopalian and Harvard Divinity School graduate named James Edward Homans; during the course of writing his defense of the faith, he had lunched occasionally with James Talmage and shared his labors with him—thus demonstrating the efficacy of intellectual ties.

Increasing numbers of Mormons by the 1920s and 1930s forged paths similar to James Talmage, traveling roads that eventually led to positions in business and the government. By the 1930s, church member J. Reuben Clark served as the U.S. ambassador to Mexico. Clark had received a law degree from Columbia, and had then served as an attorney in department of state and undersecretary of state for Calvin Coolidge. After years of public service he returned to administration within the LDS Church itself, bringing years of bureaucratic experience back to his role as a counselor in the First Presidency. In this way, through the use of channels of education, the world of Mormon Utah inched ever closer to the networks of academic and professional power, forging ties cemented by shared intellectual sensibilities and liberal religious sympathies.

THE THIRD MODE OF entry into citizenship presented by far the hardest challenge for the Mormons: acceptance into the world of American Christian leadership. Liberal Christians and academics may have been willing to take on their cause in the interest of fairness and inclusion, but evangelical Christians continued to have little use for the LDS Church. Nonetheless, the Saints tried, remaining certain that acceptance from American evangelicals would solidify their inclusion in public life. After all, some members surmised, they had a great deal in common with evangelicals in the 1910s, and they found themselves on the same side of a number of moral crusades, most notably the temperance movement. So it seemed logical for the Saints to join gatherings of evangelicals, to band together in a public display of Christian unity.

This story may sound deeply familiar to those who have followed Mitt Romney’s campaign and his early entanglements with unsympathetic evangelicals, but I want to remain in the early twentieth century just a bit longer to underscore the similarities of that moment with the current one. In 1919 the National Reform Association, an evangelical group formed during the Civil War to encourage the incorporation of explicitly Christian values into national life, held an international congress in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. James Talmage, just a few years removed from his appearance at the San Francisco Congress, seized on this meeting as an ideal time to spread his message of Mormon arrival among Christian organizations. Talmage, one of several members of the LDS Church who registered for the conference, brought with him credentials from Utah’s governor and the mayor of Salt Lake City, attesting to the fact that he was an official delegate. Initially he was delighted to be brought into the fold of concerned Christians. “It was my privilege to attend several of the meetings; and I was much impressed by the able presentation of the principal subjects, and by the liberal provision made for discussion,” he later reported.

By mid-week, however, his reception was considerably chillier. The Congress met that year in the wake of the war, and participants registered a renewed sense of both crisis and moral possibility. The world had fallen apart, and Christians saw this as an opportunity to be the first to decide how it would be put back together. Sessions were thus organized around a series of threats to the attainment of a lasting peace: participants addressed the problems of labor, of race, of economic development, and of Mormonism as an impediment to religious progress. Talmage commented, “To this commendable order of things there was one striking exception, which by contrast with all the rest of the program stands as midnight is to sunshine, as foul license is to wholesome liberty, or as pagan superstition to Christian truth.” Here is his description of the presentations about his faith that followed:

The preannounced topics included: Report of the World Commission of Mormonism; History and Tactics of Mormon Propaganda; The Mormon Menace; Mormonism and the Swiss; Defeating Mormon Proselyting. … The estimated attendance was over two thousand during the forenoon and nearly double that number in the afternoon. The chairman in announcing the opening of the “Conference on Mormonism” made plain the fact that denunciation, not investigation, would be the key-note for the day; and the appointed speakers without exception followed this lead.

Mormon Americans such as Talmage had bumped up against the immovable object of Christian citizenship. The noted anti-Mormon British author Winifred Graham spoke first, and opened the session by comparing Mormonism to the late Kaiser and his power, emphasizing that even incipient claims to inclusion needed to be stopped before they ran out of control. As she phrased it, Mormonism “claims all the privileges of a church; and it steps outside of ecclesiasticism and claims all the privileges of a political party, a commercial corporation, a secret society, a civil government.” Graham was followed immediately by a former church member, who rehearsed the litany of Mormon beliefs that other Christians found deeply offensive: the practice of polygamy, the idea that men would become gods, the secrecy of their temple rituals, the wearing of “sacred undergarments,” and the refusal of the LDS to release a complete financial accounting. The final blow was delivered by Lulu Loveland Shepard, an evangelical powerhouse and public speaker known in her day as the Silver-tongued Orator of the Rocky Mountains. Shepard was a former president of the Women Christian’s Temperance Union and a sought-after critic of the “Mormon menace.” In her address to the delegation, she called upon Christians to wake up and stop the Mormons from engulfing the nation in another Civil War. If nothing were to change, she warned ominously, the Mormon Church would gain enough power to control the government; she predicted that the church would appoint by fiat the next president of the United States, an act that would certainly lead to a war between East and West, “unless you people awake … and throttle the power of the Mormon Church.”

Talmage was aghast at the proceedings, which he described in detail in a church periodical later that year. Most instructive for our purposes is the target of his anger: he expressed astonishment that one of the speakers criticized an LDS church member who had served as a chaplain in the U.S. Army; he also seemed astounded by the charges leveled at other American Christians for allowing Mormons to become an integral part of civic life. But he expressed particular consternation that, when he passed a note to the aisle and asked to be heard during the session, he was roundly denounced. “It was voted that I be allowed to speak for five minutes as a courtesy, but with no recognition of any right to be heard, since I, not being a Christian, had no such right.” Note here the precise object of his concern: Talmage assumed that his expression of Christian belief would allow him a voice in this public setting, and that in certifying himself as both a churchgoer and an upstanding citizen (proven through affidavits brought to the conference by a non-Mormon Utah resident), he would be allowed to participate alongside other Christians in this civic display.

Here we see, in stark relief, the limits of Mormon inclusion into the American body politic in 1919. For Talmage and other Mormons of his educational and civic attainments, this reckoning came as a shock; their previous interactions with liberal Christians, with other educators, and with admiring crowds at public exhibitions, had led them to assume that their full citizenship, including a right to speak and to participate in public life, had been won by their hard-fought efforts.

1919 DID NOT MARK a conclusion to this battle: in fact, one might more accurately gauge that it was not until the 1950s that Mormons won the day. This decade was probably the apex of Mormon acceptance and civic inclusion. If we are to judge on the basis of the practices of politics in everyday life—in the participation of Saints in the government and in the educational and business sectors, and in the acknowledgement of Mormon cultural achievements, this was the Mormon moment. The popular media of the 1950s heralded the Mormon business acumen and the bevy of successful corporate leaders as a cause for admiration, and gushed that their close-knit communities presented a model of civic cooperation. In 1952 Coronet magazine published an article entitled “Those Amazing Mormons,” in which they were described as “vigorous and independent.” A New York Times Magazine writer in 1952 lauded them for their welfare program and ability to care for members. In 1965, the Pulitzer Prize-winning author Wallace Turner published The Mormon Establishment, an analysis of the LDS Church that traced its path from a small, homogeneous community with some radical economic and social ideas to a worldwide corporate and American entity. He admired the buildings lining Temple Square in Salt Lake City, he appreciated the vast church welfare system put into place during the Great Depression, and he favorably compared George Romney, then a potential contender for the Republic presidential nomination, with other moderate party members such as Mark Hatfield. With a few reservations, he concluded, he “found their doctrine to be humane, productive of progress, patriotic, wholesome and praiseworthy.” The Mormons, he concluded, had become a modern American church.

So, the question for us today is, what happened? By all measures, and certainly in the eyes of many Mormons, the Saints by 1960 had successfully assimilated into American life, demonstrating admirable civic engagement, educational attainments, and involvement with as many interdenominational religious efforts as would accept them. The church has worked long and hard to build acceptance as a legitimate player in the world of American public life. Why is it that a significant minority of people polled about their voting preferences now says that they would not vote for a Mormon candidate? And what light can this brief history shed on the reasons for that invisible boundary to Mormon citizenship?

The short answer is that America, too, has changed dramatically since the 1950s. By the early 1960s, journalists began to report more negatively on the LDS “hard sell” evangelistic techniques, their control of Utah politics, and their “rigid conservatism.” Writers expressed alarm over the “unquestioning belief” in church leaders. The Civil Rights movement, which swept away many previously segregated white churches into an interracial embrace, left the Mormons behind as holdouts in the move toward full integration of African Americans. In sum, the rules of inclusion began to change dramatically, and the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints did not seem to be keeping up with the tectonic cultural and political shifts roiling around it.

A second feature of the current political climate is the pervasiveness and cultural combativeness of anti-Mormonism. Some of the Protestant antipathy, to be sure, has been around for a long time. A movement to police the boundaries of Christianity more aggressively accompanied the growth of conservative evangelical political strength in the 1970s and 1980s. Thus, we witnessed the growth of an anti-cult movement that targeted the Mormons as a dangerous social force. The salient issue and possibly the worst offense, at this point, was that Mormon social mores were so much like those of evangelicals. Whereas in 1919 evangelicals could still use the recent legacy of polygamy to distinguish their behavior from those of the Mormons, by the 1970s Mormons seemed quite, well, conservatively Christian in their behavior. They touted wholesome family values, they supported traditional roles for women, and they practiced an admirable fastidiousness toward the use of coffee, alcohol, and cigarettes.

In the current moment, too, Mormons have fewer liberal sympathizers and more enemies. Now, we see atheists who are cultural combatants every bit as assertive as their evangelical counterparts, and we hear regularly from liberal pundits such as Maureen Dowd and Lawrence O’Donnell as they invoke temple rituals and sacred undergarments to measure the oddities of Mormons. Currently, the church seems to be getting it from all sides.

For Saints themselves, this negative response can seem quite puzzling in light of their history of steadily increasing acceptance. They thought they knew how to be citizens, how to participate and to be included as full members of the body politic. They have practiced for a century, tinkering with the formula when necessary, and yet their efforts still don’t seem to be good enough for other Americans, who keep moving the bar in response. This dynamic raises an interesting theoretical question, for which we still don’t have an answer: what would Mormons have to do, short of renouncing their religion, to be accepted in the public square? As the Saints have attempted to resolve the dilemma of Mormon citizenship, the stakes of the long Mormon moment have crystallized in this election cycle. Mitt Romney’s candidacy has served as only the latest catalyst to solidify the tensions and problems of a long and complex history.

Laurie F. Maffly-Kipp is Chair of the Department of Religious Studies at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. This article is based on a lecture she gave in April at the John C. Danforth Center on Religion & Politics.

Further Reading:

- Thomas G. Alexander, Mormonism in Transition: A History of the Latter-day Saints, 1890-1930 (Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1986).

- Randy Astle, “One Hundred Years of Mormonism,” at Mormonism and the Creative Arts.

- Randy Astle, “Nephi’s Colored Plates,” Glimpses: Newsletter of Mormon Artists Group (July 2008).

- Mrs. Theodore Cory, “Report of World Commission on Mormonism,” in The World’s Moral Problems, addresses at the third World’s Christian Citizenship Conference (Pittsburgh: National Reform Association, 1920).

- John-Charles Duffy, “Conservative Pluralists: The Cultural Politics of Mormon-Evangelical Dialogue in the United States at the turn of the Twenty-First Century” (Ph.D. diss., The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 2011).

- John Henry Evans, One Hundred Years of Mormonism (Salt Lake City: Deseret News, 1905).

- Reid Neilson, Exhibiting Mormonism: The Latter-day Saints and the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011).

- Kathleen Flake, The Politics of American Religious Identity: The Seating of Senator Reed Smoot, Mormon Apostle (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2003).

- James P. Harris, ed., The Essential James E. Talmage (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 1997), introduction available here.

- Eber D. Howe, Mormonism Unvailed (Painesville, OH: By the author, 1834).

- Elizabeth Wood Kane, Twelve Mormon Homes (Philadelphia: n.p., 1874).

- Dennis L. Lythgoe, “The Changing Image of Mormonism,” Dialogue, vol. 3, no. 4, 47, 48.

- D. Michael Quinn, Elder Statesman: The Biography of J. Reuben Clark (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 2002).

- Lulu Loveland Shepard, “The Menace of Mormonism,” World’s Moral Problems.

- Jan Shipps, Mormonism: The Story of a New Religious Tradition (Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1985).

- John R. Talmage, The Talmage Story: Life of James E. Talmage, Educator, Scientist, Apostle (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1973).

- James Talmage, “Christianity Falsely So-Called: A Late Instance of Intolerance and Bigotry,” Improvement Era 23 (1919).

- Wallace Turner, The Mormon Establishment (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1965).